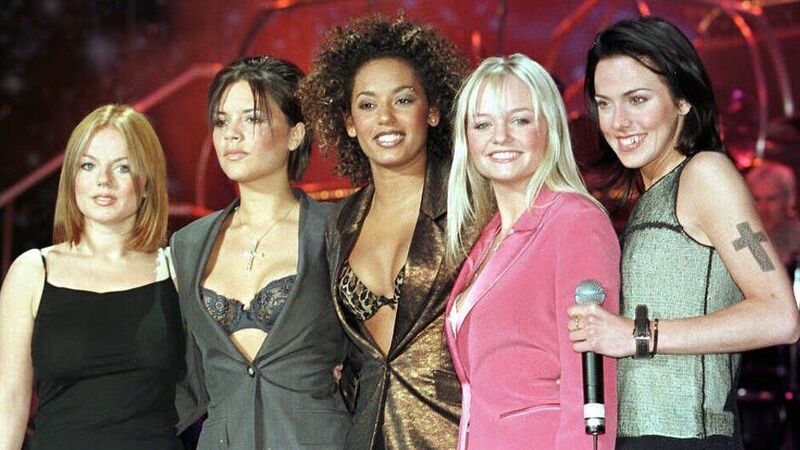

Girl power — we’ve come a long way

Never has one group of human beings been so singled out, so fetishised, so agonised over, so over-protected, so wrapped up in cultural projection and expectation.

We are obsessed with girls, in all their inexperience, their potential, and their power. Girls make us drool, gawp, panic, fret, moralise, pontificate. We get ourselves in a right tizz about them. This tizz is beautifully analysed by social historian Carol Dyhouse, in her latest book, Girl Trouble: Panic and Progress In The History Of Young Women, which examines the journey of the girl in the 20th century.