Breaking silence through cinema

Alex Gibney is one of the foremost figures in documentary filmmaking, famous for his exposés, of capitalism in Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, and US military torture in Taxi to the Dark Side. The latter won him an Oscar in 2008.

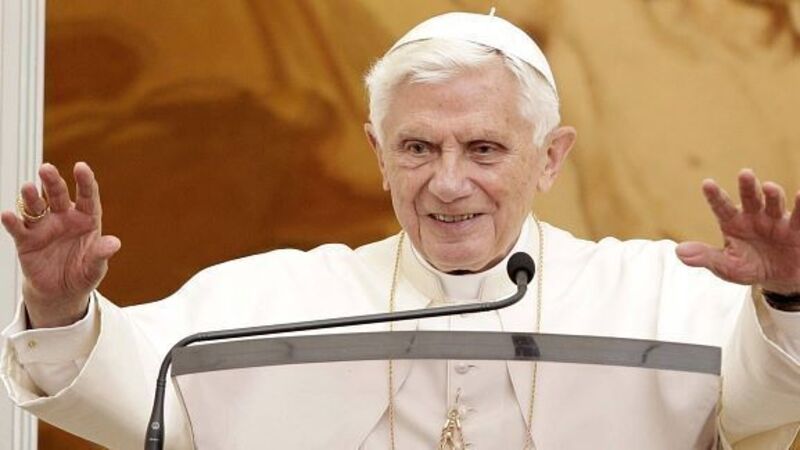

The American’s latest film, Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God, is the story of four deaf men sexually abused by a priest at their school in Milwaukee in the mid-1960s. It interrogates the Catholic Church’s abject reaction to child abuse. Such is the scope of the film it’s possible it has even played a part in the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI. The Pope’s possible legal culpability informs one strand of the film.