Tame your toddler

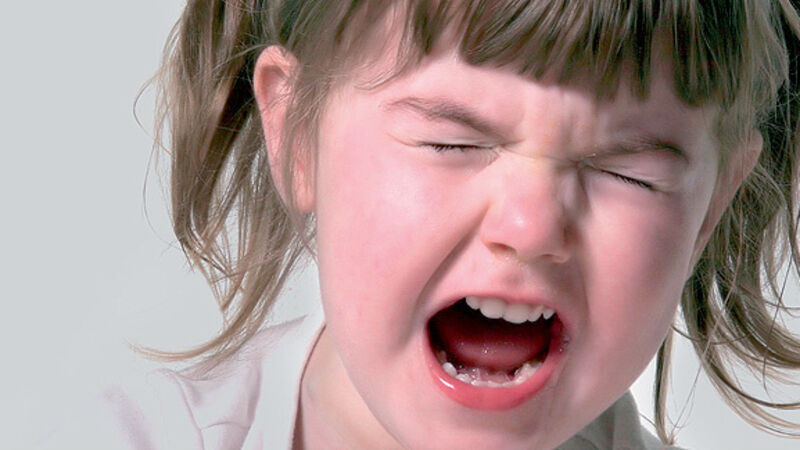

IN an hour, my two daughters, Evelyn (three-and-a-half) and Isabel (two), have run the gamut of emotion: shy giggles, overexcited yelps of laughter, tears, and an unsolicited cuddle from Izzy for the photographer.

It’s been an odd morning (a large part of our small house has been transformed into a photo studio, and there are lots of strange, new people to show off in front of). As fatigue sets in, the inevitable tantrums occur.