Fighting a losing battle

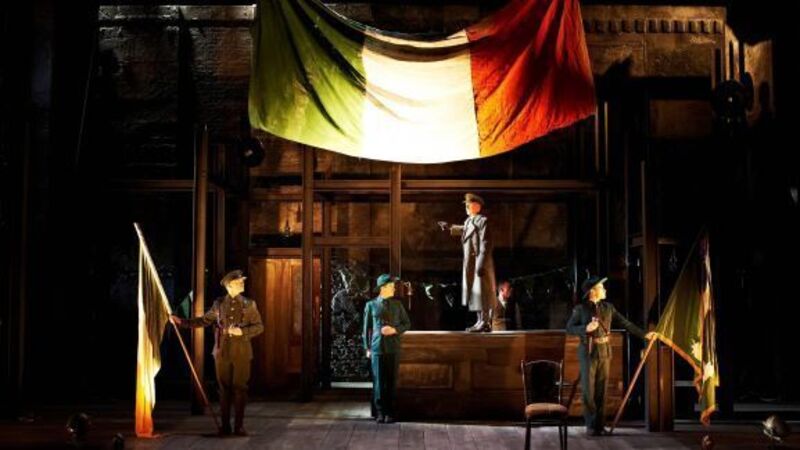

PRESENTED by the Abbey Theatre, Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars begins its run at the O’Reilly Theatre on Great Denmark Street in Dublin this week. The main stage of the Abbey is being renovated, but the play will return there on Sept 15, before touring the UK and Ireland. The last time The Plough and the Stars moved to an outside theatre was after the fire of 1951, which gutted the original Abbey.

With the hundredth anniversary of the 1916 Rising looming, narratives of the War of Independence will be revisited by historians and commentators. O’Casey’s tale of rebellion, suffering, love and loyalty is a good place to start.