Special Report: Breaking the farming stigma around hemp

Try from €1.50 / week

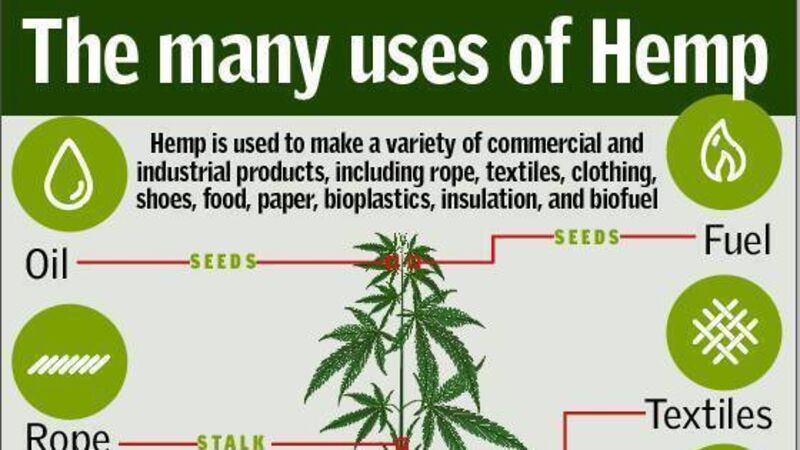

SUBSCRIBEHemp is a “high-value crop”, is very pest resistant, low maintenance to grow, and has over 50,000 different product applications.

And yet, one of the biggest things holding it back is the “stigma” that surrounds it.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

Newsletter

Keep up-to-date with all the latest developments in Farming with our weekly newsletter.

Newsletter

Keep up-to-date with all the latest developments in Farming with our weekly newsletter.

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 6:00 PM

Sunday, February 8, 2026 - 1:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited