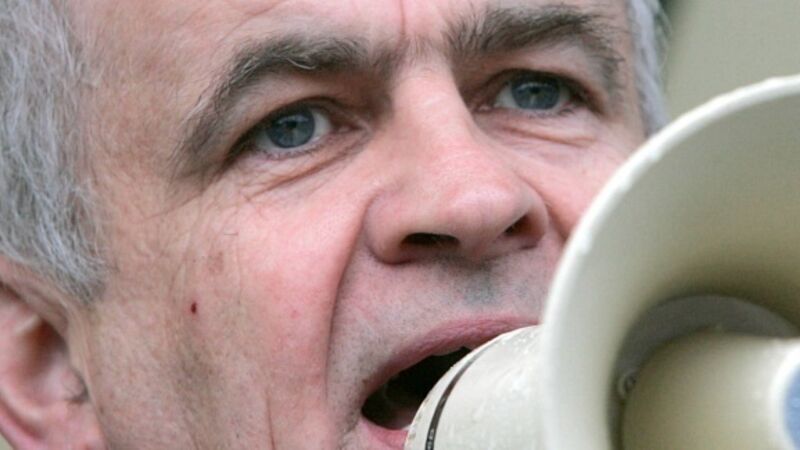

Stephen Cadogan: The big investors know how important our farmers are

He said farmers must be fairly rewarded for their high quality production, and high environmental and animal welfare standards.

It would be unusual if the main farming organisation wasn’t looking for more money for its members.

And the government are unlikely to sit up and take much notice of yet another call for help, when so many sectors are looking for relief as they struggle through the recession.

But even more powerful people have been listening to the complaints of farmers.

They have been taking note of the fast rising average age of farmers in Europe, America and New Zealand, who are now in their late fifties, in these agricultural powerhouse countries. They often have no successor, because offspring do not want to farm, or they cannot afford to buy out family members.

Ireland is no exception, with the average age of farmers rising from 50 to 54, between 2000 and 2010. More than half were aged 55 years or older, more than a quarter were aged over 65 years. The number of farmers under 35 years, more than halved to less than 6% of farmers.

And like farmers everywhere, they don’t earn enough to have the major financial resources which are needed to invest in the top new farm technologies and expand their production to a more profitable scale.

Meanwhile, experts on global nutrition say farmers will need to produce more food in the next 40 years than in the previous 10,000 years.

Among the people who have been listening and putting all this information together were the asset managers at Aquila Capital, who look after assets of over €7.9bn for investors. They say 30,000 hectares of farmland are lost every day, and 200,000 extra mouths to feed are added to the world’s population.

They reveal that 23% of investors are looking to take on more farmland over the next one to two years, and only 2.3% plan to reduce it.

Some of the large institutions now investing in farms include the China Investment Corporation, and Temasek Holdings, owned by the Government of Singapore.

In 2009, the Hassad sovereign-wealth fund in Qatarbought nearly 50 farms in Australia, to merge them into a single investment portfolio.

Terrapin Palisades, a private-equity firm, converted farms in California to grow almonds. They had the necessary up-front capital and could survive without returns for years, until production increased to take advantage of the rising price of almonds, which is linked to increasing Chinese demand.

Investors see the great value in farming, and have the capital to unlock it, unlike the families which own nine out of ten of the world’s farms.

In some countries, investors can simply change ancient irrigation canal networks to automatic spray systems, and reap major returns.

Or they can invest in robots to boost milk per cow 10-15%.

They can use precision farming and “big-data” to push crop yields up 5%.

They know that the gap between top and bottom performers is greater in farming than any other industry, and they have the capital to profitably take over and improve poorer performing farms.

Some investors believe farmland will be as profitable a sector for them as real estate and infrastructure have been.

In the US, investment in farmland has yielded annual returns of 12% over the past 20 years, outperforming most major asset classes.

It is an ideal diversification for investors, resistant to inflation, less sensitive to economic shocks and interest-rate hikes, and unaffected by slumps in assets such as stocks and bonds.

These investors, rather than the food markets, could yet be IFA’s best hope for a better wage for their members.

Maybe IFA should be seeking out financial deals in joint ventures with investors, now that the farm gates which were traditionally closed to capital markets are opening.

Maybe investors will better appreciate and reward the increasingly important role of our farmers than the food markets or the EU or national governments.