New markets elude Ireland and EU as reliance on agriculture stalls deals

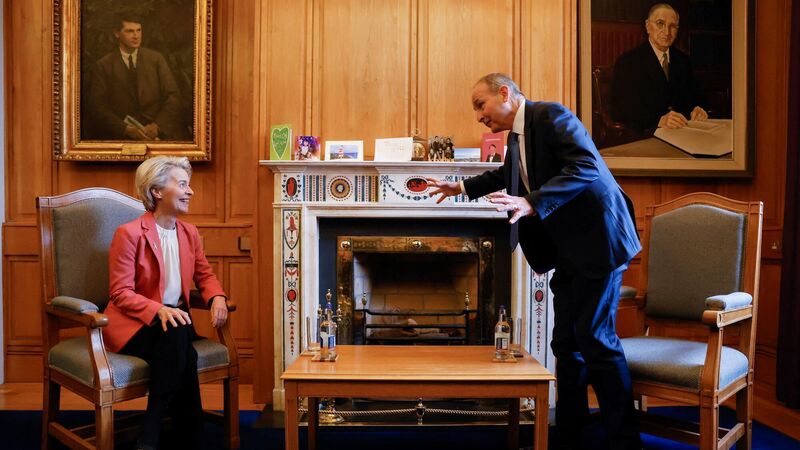

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen with Taoiseach Micheal Martin. Brussels has struggled to close agreements in recent years because of sensitivities in its 27 member states over agricultural produce. Picture: Clodagh Kilcoyne/PA Wire

US president Donald Trump's hostility to established international trade agreements and his willingness to inflict trade damage on friend and foe alike, has created a major dilemma for foreign government officials.

Should they curry favour with the US in the hope of easing tariffs and hold on to exports to the US? Or should they scurry around the world, seeking ways to find new export markets outside the ambit of the US?