Trump failure to appoint ambassador to Ireland is cause for concern

The US ambassador to Ireland is a vital role and Donald Trump’s failure to fill the post is cause for concern, writes .

US President Donald Trump’s apparent disdain for diplomacy and lack of engagement with human rights issues is causing growing disquiet in the US state department, as dozens of diplomatic posts remain unfilled around the world — including that of ambassador to Ireland.

The US Embassy in Dublin says the post is “highly coveted”, yet it has been vacant now for almost a year and at a time when having diplomatic friends in high places, whether in Brussels or Washington, is crucial in our push against the perils of Brexit.

We have only to look back at Ambassador Jean Kennedy Smith’s work during the peace process two decades ago to see how vital the post can be at critical points in our history.

The previous envoy, Kevin O’Malley, left the post in January when Barack Obama’s term of office ended and Donald Trump’s began.

The president was close to nominating businessman Brian Burns earlier this year but Mr Burns withdrew his name, citing ill health.

These things just take time to get right, according to the US embassy. “The US ambassadorship to Ireland is a highly coveted position, reflecting the importance of the bilateral partnership and the deep historical ties between our two countries,” a spokesman told me.

“Selecting the right candidate for the position can be a lengthy process, which involves nomination by the president, careful vetting and then confirmation by the US senate.”

Until that process is complete, he said, Chargé d’Affaires Reece Smyth will continue to lead the embassy in Dublin.

But the disquiet in Washington can hardly be making the process any easier. There is a reluctance to go on the record, but one senior diplomat recently spoke out about it.

In her resignation letter, reported in Foreign Policy magazine, Elizabeth Shackelford, a political officer with the US mission to Somalia, accused secretary of state Rex Tillerson and the Trump administration of undercutting the state department and damaging America’s influence in the world.

She claimed the administration had abandoned human rights as a priority and shown disdain for diplomacy.

The state department’s role had “diminished,” she wrote, with the White House handing over authority to the Pentagon to shape foreign policy.

Similar concerns were expressed earlier this year by then-top US army commander in Europe, Lieutenant-General Ben Hodges, who said Mr Trump’s failure to appoint a number of ambassadors risked damaging American interests. As well as Ireland, some 40 other states out of a total of 188 are also without envoys, while the UK only got an ambassador in August.

But what really happens when the White House does settle on a candidate? This is how the process unfolded inside the Oval Office four decades ago when another president got ready to interview the candidate for the Dublin post.

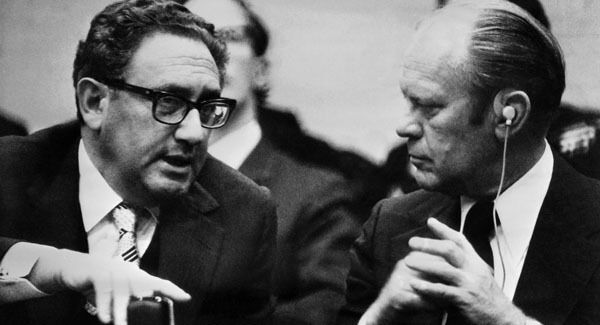

First, president Gerald Ford consulted his top diplomat Henry Kissinger. An unusual consensus developed: The less political experience the candidate had, the better. But these were unusual times. It was 1975 and America had been traumatised by the Watergate scandal, and Kissinger’s previous boss, president Richard Nixon, had resigned. Politics was in “swamp” territory.

Kissinger, therefore, wanted to make sure the candidate for the Dublin post, New York financier Walter JP Curley, commissioner of public events for New York City, lacked any murky political connections. He got straight to the point: “What are your political contributions, commissioner?”

Curley feared the worst: “Well, this may be the end of the interview, but as far as my financial contribution goes, basically none at all.” But it was exactly what Kissinger wanted to hear: “Very good, very good,” he told a bemused Curley. “We want clean-as-a-hound’s- tooth here.” A formal White House interview was arranged.

President Ford and deputy assistant for national security affairs, Brent Scowcroft, greeted Curley as he entered the Oval Office on September 2, 1975.

Ford’s first comment was about events in Ireland the same day, where Éamon de Valera had died and 200,000 people had lined the streets of Dublin for a State funeral for the former president. “This is a big day in Ireland,” Ford remarked. “It will be a big funeral,” Curley responded.

Perhaps keen to ensure Kissinger had done the necessary political vetting, Ford then asked: “Are you a relative of the Boston Curley?” It was a key question, even an intriguing one. The “Boston Curley” was a reference to the deceased but legendary Irish-American politician James Michael Curley.

James Michael had served variously as a congressman, mayor of Boston and governor of Massachusetts, but had been dogged by corruption. He’d been twice convicted of crimes and was imprisoned for a felony conviction.

Candidate Curley would have been aware that any links, real or imagined, to such a politically unsavoury Curley would probably have been the kiss of death. “ No, I can’t claim that,” was his somewhat stilted response as recorded in the 2004 declassified White House papers from the Ford Presidential Library.

While it wasn’t quite a resounding “no”, it did the trick. Ford dropped the matter and turned to Irish politics.

“I’m sure you know how important we consider our relations with Ireland, and I’m sure that State [department] has told you the problems of North Ireland [sic] and how we try to stay out of it. Does anyone have the answer to it?” Curley, who had relatives in Limerick and a house in Mayo, knew from his discussions with Kissinger to tread carefully.

Any solution was elusive, he responded, “but it is not for lack of trying. I heard that all the men who are caught in those various clashes are unemployed. Maybe economic betterment is the solution.”

President Ford probed further: “I read in the paper that the IRA has stolen weapons from our military. Is that true?” he asked.

This time it was Scowcroft who responded. “Yes,” he told Ford. “Most of the stealing is from the National Guard or Reserve armouries. But there have been several cases of substantial gun running.” Then it was all over. “I want to wish you every success and I know you will be an outstanding representative of the US,” Ford told his new ambassador to Ireland.

Walter Curley’s death last year, at 93, has focused fresh attention on his role as ambassador from 1975 to 1977 during a turbulent period in Ireland and a time of profound change in the relationship between Ireland and America.

Ireland was a stimulating place “historically, politically and intellectually” and was “becoming more cosmopolitan,” Curley recalled years later in an interview about his tenure in Dublin for the US Diplomatic Oral History series. Ireland had joined the EEC two years before he arrived and was holding the revolving presidency.

“The Irish had been turned historically towards the New World. The United States was where they looked for help and inspiration and protection and familial ties,” he said.

“But gradually that changed and the Irish turned to Europe and were more and more considering themselves not as an extension of the UK or America but really as Europeans. They were Irish first and relishing the fact they were European, not American-oriented.”

A year before Curley’s arrival the Dublin and Monaghan bombings had killed 34 people. “The bad days were back,” he recalled. “They hit an apex of pain when my best friend among the diplomatic community, the British Ambassador [Christopher Ewart-Biggs], was assassinated. Sad and disgusting.” Curley was determined to do something about the money for arms that the IRA was receiving from Irish-American sources.

“So, surreptitiously, the British Secret Service, the FBI, the CIA, the Irish intelligence service, the Irish military and, of course, myself, we all colluded to find out exactly how much money was coming in. We tried to apply some effective restrictions, and I think it worked pretty well. We did it for about two years, and at the end of the two years I figured that the flow of money to the IRA was reduced to a million dollars a year.”

A year after he left Dublin in 1977, Curley got a call from his pal George HW Bush, asking for help in seeking the US presidency. When Bush became president in 1989, he nominated Curley as his ambassador to France.

But for all the delights and challenges Paris offered, Ireland still held a special place in his heart and over the years he frequently visited his house in Mayo, not far from the Galway birthpace of his namesake James Michael Curley.

“I like the Irish. I like the way they think,” Ambassador Curley once said. “There are many different kinds of Irish: Irish-Irish, Anglo-Irish, Norman-Irish, Protestant-Irish, Catholic-Irish, all kinds.” He might well have added there are also all kinds of Curleys.

Just, indeed, as there are all kinds of presidents and, regardless of president Ford’s playbook, President Trump will undoubtedly follow his own script when he finally picks his Irish envoy.