BIG READ: The Avenatti Effect - The lawyer, the porn star, and the plan to take down a president

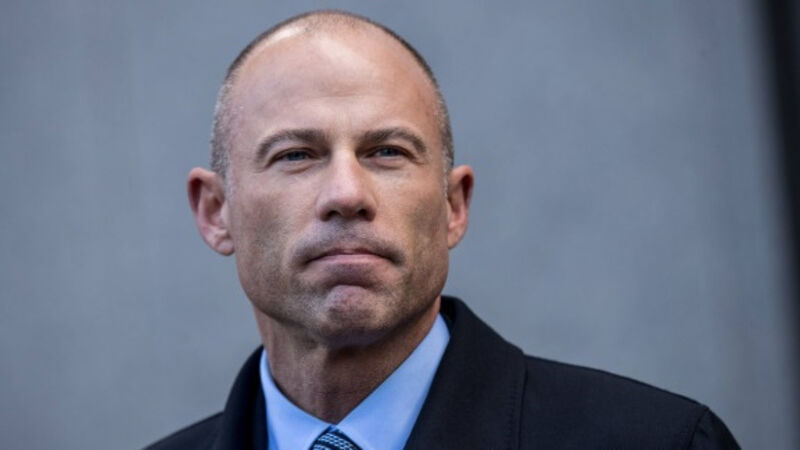

THE lawyer Michael Avenatti stands just under six feet tall, with blatant blue eyes and thinning hair, which he shaves down to stubble, exposing the crumpled vein at his left temple.