Journalistic privilege acknowledged in law but is not absolute

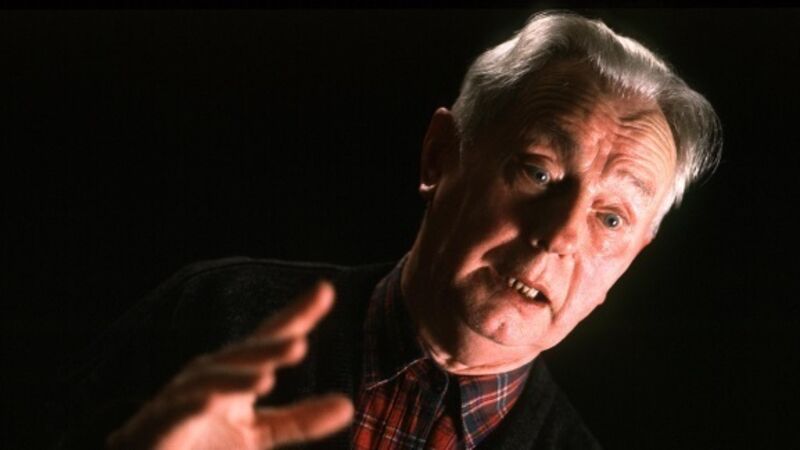

If the opening statement at the Disclosures Tribunal issued by Mr Justice Peter Charleton is anything to go by, he has hit the ground running in attempting to deduce whether senior garda figures and/or their agents acted maliciously towards Sergeant Maurice McCabe and others.

Central to that is the issue of what privilege — if any — attaches to communications either given to or received by journalists reporting on the whistleblower scandal.