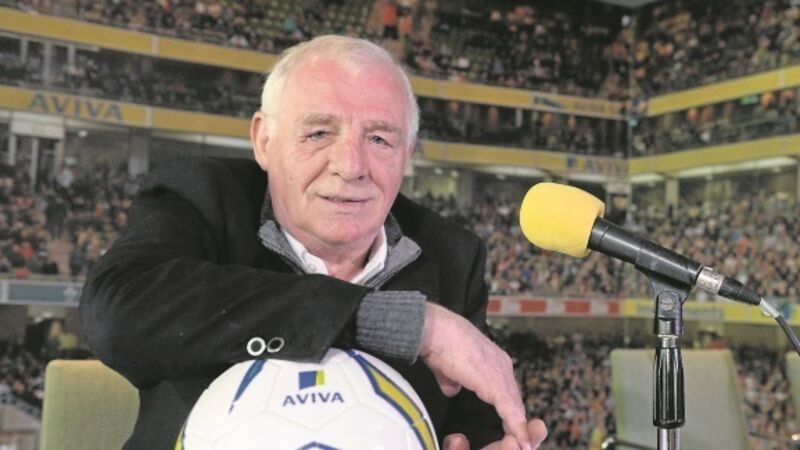

The Eamon Dunphy Interview: 'I wanted to tell the story of the life of an ordinary footballer'

You’ve come over to Eamon Dunphy’s house in Ranelagh to talk about the 40th anniversary and another reprint of Only A Game? But this being Dunphy and politics dominating the news agenda, invariably you end up having a chat about a lot more than Only A Game? and only sport.

He was out canvassing before the election. For the Independent Alliance. Not just in Dublin with his old friend Shane Ross, but as far as Sligo where a Marie Casserly — “a teacher, a community worker, not a professional politician, an excellent candidate” — ran. And if at first it strikes you as a bit strange, that a now 70-year-old Dunphy would travel across the country to knock on doors for someone you’d never heard of (Casserly would muster just 4.4% of first preferences), you later learn there’s a reason why. There’s still a fire, even an anger, in the man.