Sat, 08 Sep, 2012 - 01:00

Sue Leonard

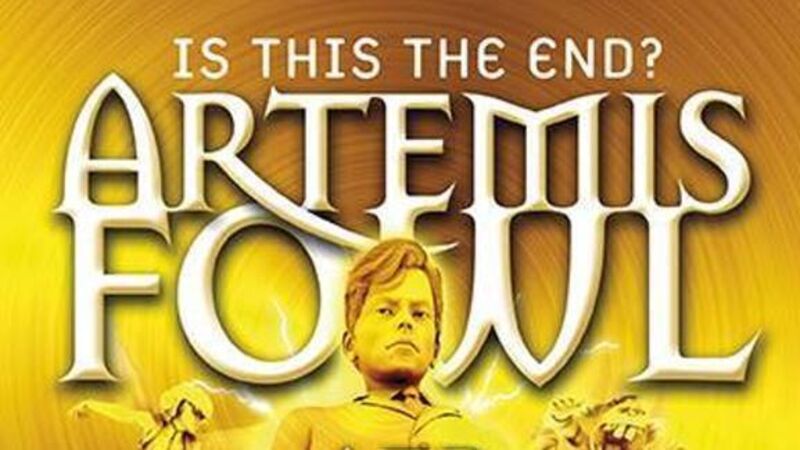

Eoin Colfer

Puffin, €13.99;

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

CourtsArts Film & TVBooksPlace: AustraliaPlace: New ZealandPlace: Hong-KongPlace: CoPlace: San Andreas faultPlace: VesuviusPlace: IcelandPerson: Eoin ColferPerson: Sue LeonardPerson: EnniscorthyPerson: EoinPerson: ColferPerson: ArtemisPerson: FinnPerson: DonalPerson: Artemis FowlPerson: Captain HookPerson: HarryPerson: JK RowlingPerson: Anthony HorowitzPerson: Alex RyderPerson: Douglas AdamsOrganisation: New York TimesOrganisation: O’Brien Press