An act of love and redemption

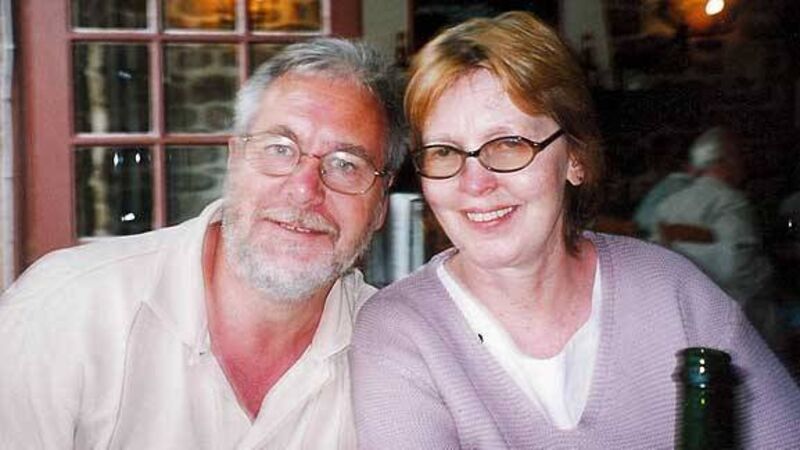

I FIRST met Marie Fleming at the start of March 2013. She had taken her High Court and Supreme Court challenges against the State, fighting for the right to be helped to die with dignity, but judgement was not yet delivered.

I’d seen her on the TV news, and read her brave testimony in the papers, and I admired her enormously.