A historian’s quest for Richard the Lionheart

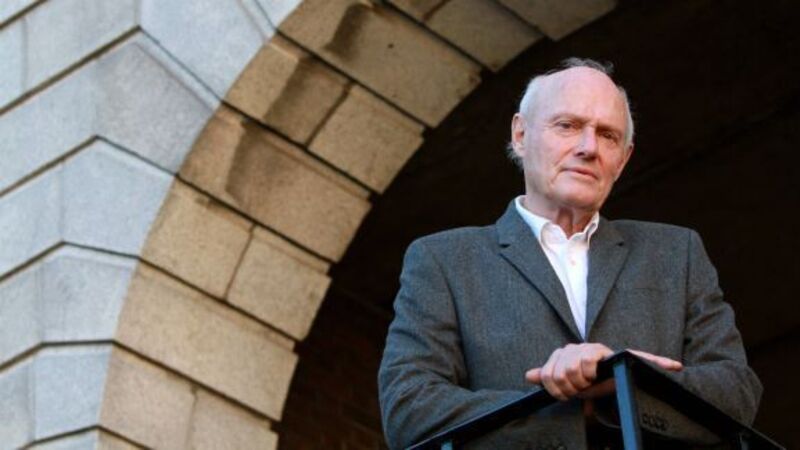

WRITING makes Justin Cartwright happy. That and tennis keep the 68-year-old calm. But he hates the two weeks prior to publication, before the reviews. Winner of numerous prizes for his novels, he shouldn’t worry; but the odd critic has been vindictive.

I’m a huge admirer of Cartwright’s writing.