Maresa Fagan: Knock-on effect of Covid-19 leaves cancer test backlog

File photo of a consultant analyzing a mammogram.

There are so many dark sides to Covid-19. In addition to the growing global death toll, now well above one million, it is wreaking havoc on our social and economic wellbeing, as well as health services around the world.

This point was plain to see in Ireland from the very outset of the pandemic, when we shut down our health service and braced ourselves for the worst.

Since then we have come out of the emergency phase and resumed most services, but pressures remain and are further heightened given the expected winter demands, reduced capacity, and need to operate Covid and non-Covid services.

And as we step into winter, we are now beginning to see the long-lasting and damaging impact of suspending services in March.

While we had little choice but to do so in the face of the Covid-19 emergency, the ongoing pandemic is now exposing the deep cracks within our health service at all levels.

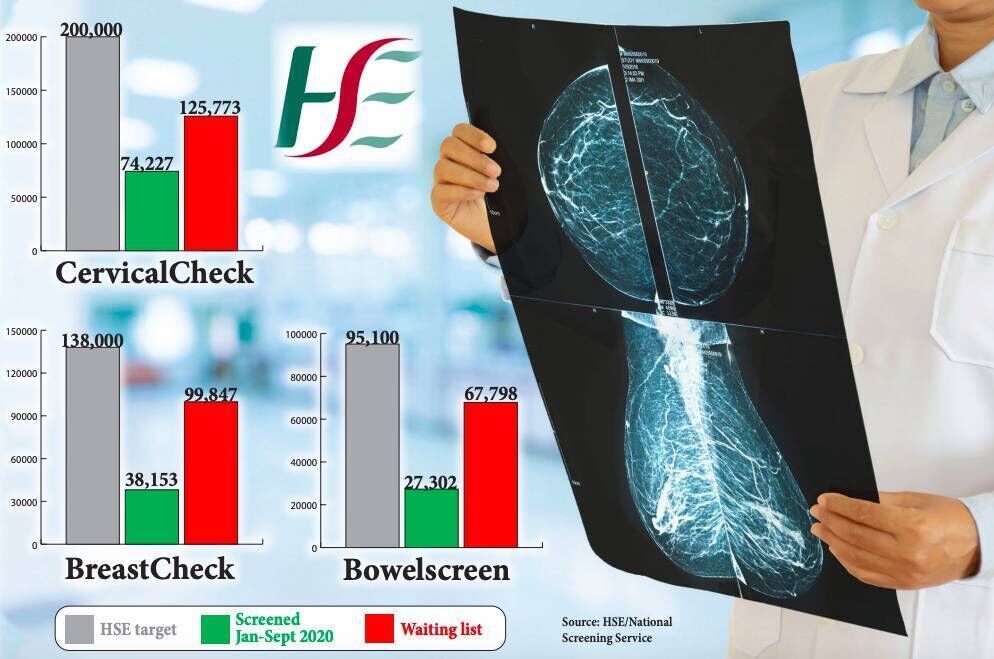

New figures provided by the National Screening Service, which manages three cancer screening programmes, are evidence of this.

More than 430,000 women and men were due for either breast, bowel, or cervical cancer screening this year, but a pause in services has created a backlog of hundreds of thousands who are now waiting for a test.

Just one-third of the 2020 annual target had been screened by the end of September, leaving close to 300,000 people waiting for tests and appointments.

There are now signs that the cervical screening programme, CervicalCheck, which was the first to resume in July, is beginning to catch up on screening invites, with all women due for screening in 2020 expected to receive an invite before the year-end.

Women are invited to book their appointments as soon as possible. GPs, who largely carry out tests for the screening programme, however, are already under pressure — and this is where a bottleneck may emerge.

If anything, the situation highlights how fragile our health service is and how we cannot afford further delays or suspensions to services.

This point was brought home by CervicalCheck clinical director Dr Nóirín Rusell, who has warned that further delays will follow in 2021 if women do not take up their appointments this year.

While CervicalCheck relies on GPs, in the main, to carry out tests, the challenges facing the BreastCheck and BowelScreen programmes are further compounded by Covid-19 social-distancing and infection-control requirements.

Women attending for a mammogram, for example, do so at BreastCheck clinics or mobile units, which have had to scale back on activity levels because of these restrictions.

For this reason, the service expects that it could take three years to get through the normal two-year cycle of women to be screened.

Any new targets to catch up on waiting lists and backlogs will be contingent on holding our current position and avoiding a worsening Covid-19 picture.

Of more concern are delays in cancer diagnostic services, where patients are urgently referred if they present with symptoms that could point to cancer.

Targets were being missed even before Covid-19 arrived this year, as services were already under pressure.

The percentage of patients seen on time at rapid-access clinics for breast, lung, and prostate cancer was 26% below target in December last year, according to the latest performance figures available.

Other figures show that 2,400 people are awaiting urgent endoscope tests for potential cancers, with one quarter waiting more than three months. The tests are meant to be carried out within a month.

All of this highlights the pressures facing an already overburdened service that has limped on and kept going, winter after winter, crisis after crisis.

Commenting on staffing gaps and service delays, oncologist Professor John Crown borrowed from the civil rights movement this week when he said: “Treatment delayed is treatment denied”.

He is not wrong, and only time will reveal the scale of the fallout.