Clodagh Finn: More pockets in women’s clothes, please

'Miserable faux pockets that aren’t sewn shut are another fashion abomination that has robbed us of the instant access to a well-made pocket.'

HISTORY HUB

If you are interested in this article then no doubt you will enjoy exploring the various history collections and content in our history hub. Check it out HERE and happy reading

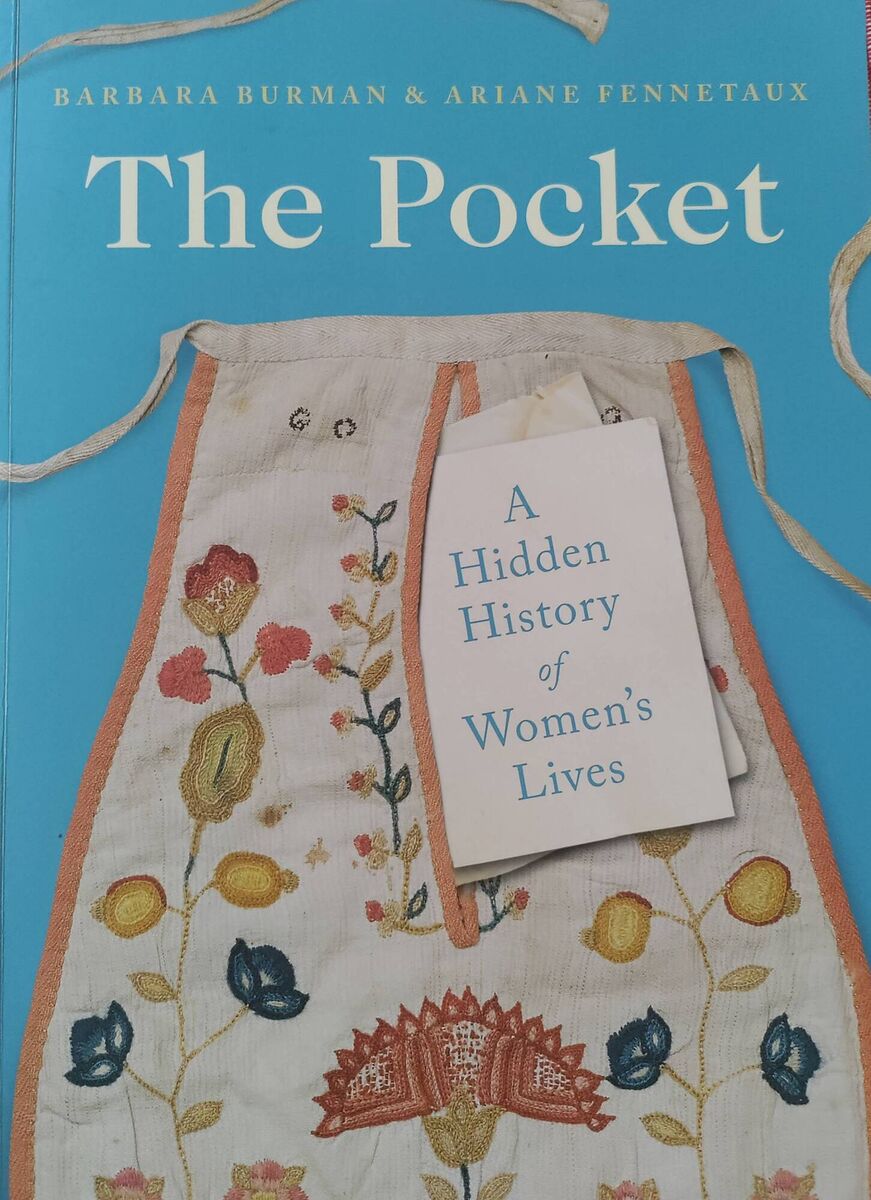

The first pockets were sewn into men’s trousers — but not women’s clothing. Instead, from the late 17th to 19th centuries, women wore tie-on pockets. And it wasn’t long before the pocket, like so many other items of female clothing, was embroidered with a range of meaning.

And yet when it went out of fashion to be replaced by the reticule or purse, women protested about the loss. Burman and Fennetaux recall how American women’s rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton described the losing battle she had with her dressmaker in 1895 when she asked for pockets in her dress. Pocket-less clothes hampered women’s mobility and independence, she argued.