Clodagh Finn: A guide to hospitality when we most need it

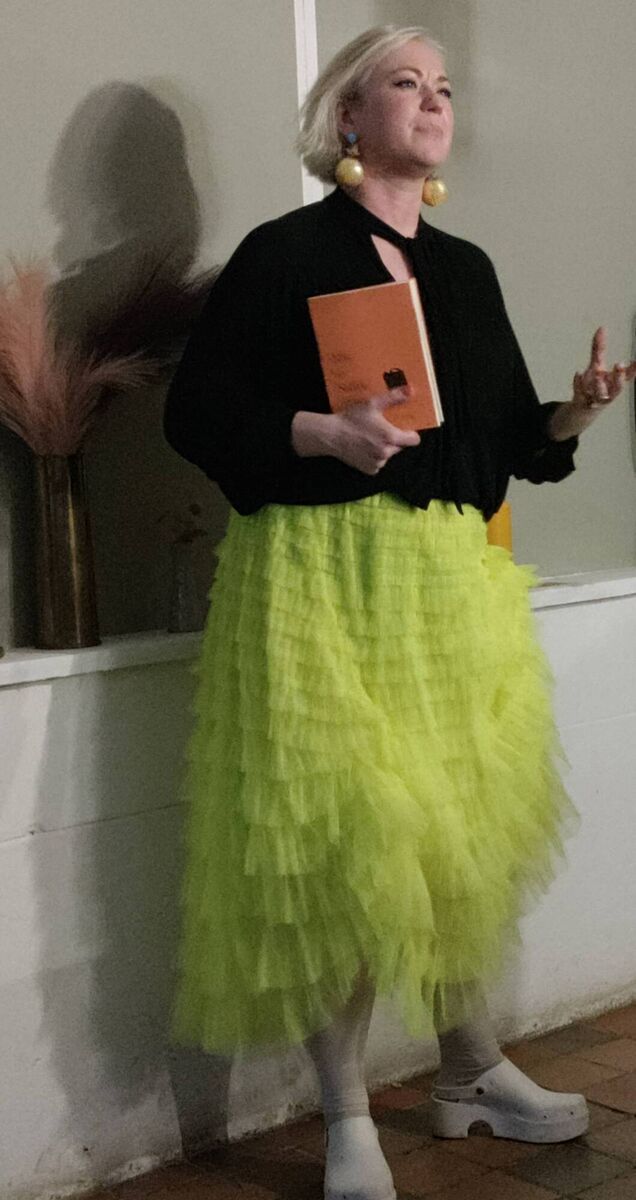

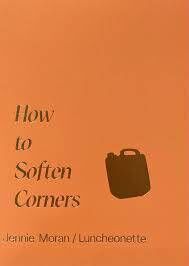

Artist Jennie Moran. Her book, beautifully produced and beautifully written, expands on the philosophy of hospitality.

HISTORY HUB

If you are interested in this article then no doubt you will enjoy exploring the various history collections and content in our history hub. Check it out HERE and happy reading

“We humans endure lots of harsh landscapes in our daily lives —boundaries, borders, barriers, lines not to be crossed. But we are a non-geometric shaped species. Our bodies do not contain straight lines or 90° angles… We need breaks from straight lines. We need to touch things that are porous and might yield to us. We also need to feel minded and held by a space, adjacent to other humans.”

It is described as a playful how-to guide to hospitality — which it is certainly is — but it is also a lyrical reminder of the importance of nurturing human connection.