Save our rivers: The many faces of the Suir — and how endangered freshwater mussels could help

A new accessibility initiative? No, this photo of people kayaking on the Suir in the heart of Thurles was taken in the 1990s by Eamon Brennan. Decades later, Eamon's nephew Melvin Brennan is advocating for such access to the river.

Melvin Brennan is of the Féile generation. He grew up in Thurles, leaving at 19 when the annual festival at Semple Stadium hit its peak: The Féile ’95 line-up, featuring The Prodigy, Moby, Blur, and the Stone Roses, is often referred to as the best Irish music festival line-up ever.

All his years growing up in the town, he says he and his peers took access to the River Suir for granted.

"We would have been down by the river every summer as kids, jumping in and out of the water," he says.

“A lot of people would have hung out down there in the summer — elderly people, young people.”

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB

Mr Brennan lived in Dublin for many years before moving back to Tipperary. He now runs the Love Thurles Facebook page, frequently posting photos taken by his uncle, well-known local photographer Eamon Brennan.

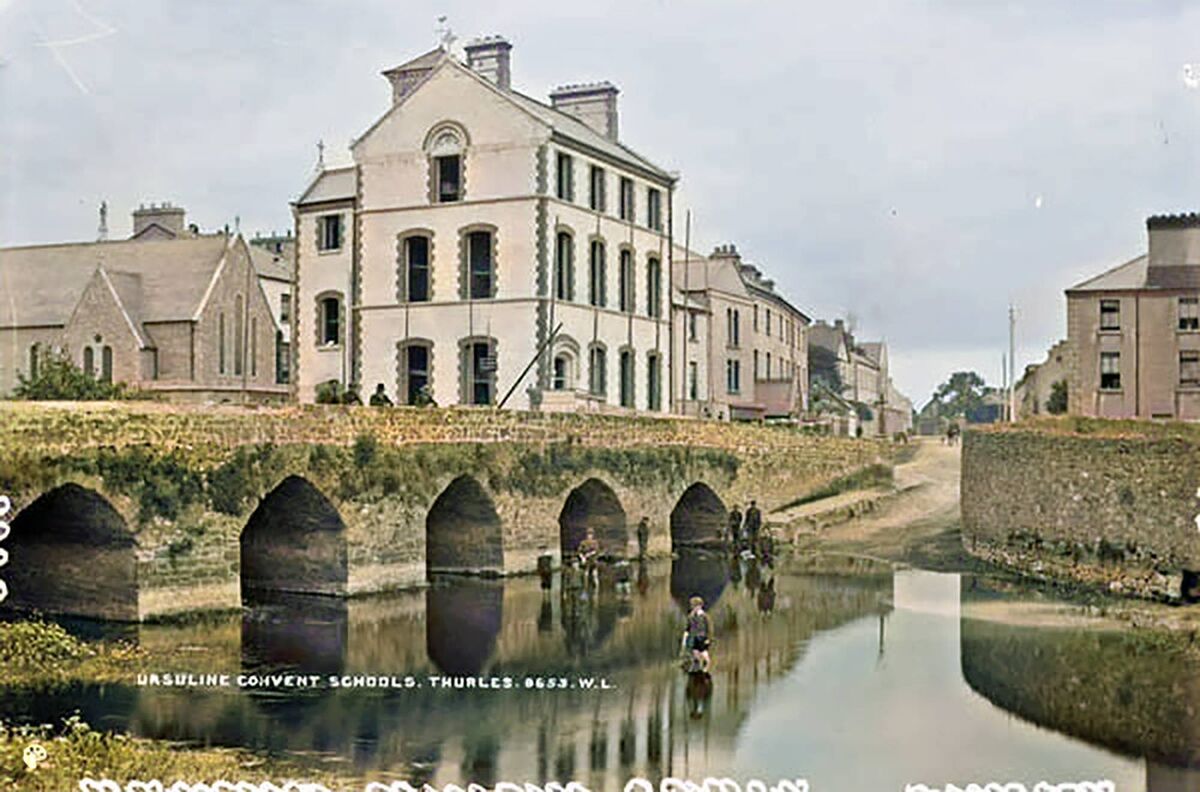

Among Eamon Brennan’s snaps of the happy chaos of Thurles town during Féile, there are some that show the river in use: gaggles of teens perched along the banks while other young people are taking a kayaking lesson below the weir next to the 17th-century Barry’s Bridge (or Thurles Bridge).

It’s not a scene that could be replicated today.

River bank development in the intervening years has reduced open access to the water, and Melvin Brennan and other residents take exception to recent policy changes that mean that the river is no longer being cleared of vegetation.

“They’ve just basically allowed it to overgrow, and the river flow is getting very low,” Melvin Brennan says.

“I contacted Thurles tidy towns group a couple of years ago, and offered to get a couple of lads and go in and pull it, and I was told leave everything alone and that the algae could be taken out and nothing else. I was told it was for biodiversity.

“In recent years, you notice that where the river is low in the town, there is a lot of algae and it smells in the summer. But I barely even look into the river any more, because it drives me nuts and it’s driving a lot of other people mad as well.”

Read More

For the past few years, Mr Brennan, like his uncle before him, has been photographing the Suir in Thurles town. But, unlike his uncle’s photos of lazy summer days on the water and picturesque winter snows and wildfowl, Mr Brennan’s photos are of algal blooms, shopping trolleys, litter, and even raw sewage.

The Source Arts Centre now stands at the site where Eamon Brennan once photographed teen kayakers. On the other side of the river, there is a 300 metre river walk known by locals as the Watery Mall, behind modern developments in the form of supermarkets and the garda station.

It’s well known in the area that untreated sewage is flowing into the river near Thurles Shopping Centre.

At a Tipperary County Council meeting in January, representatives of the Local Authority Waters Programme told the council that “the issue in relation to the discharge of raw sewage into the River Suir at the back of Thurles Shopping Centre is the responsibility of Uisce Éireann, who are aware of the problem and Tipperary County Council have had a number of meetings with UE on this matter”.

When a river’s flow is low, this impacts its dilution factor and its ability to carry off pollutants.

EPA sampling of water at Thurles Bridge in 2023 found the water to be of “poor” quality, the second worst possible value on a five point scale of high, good, moderate, poor, and bad.

“Tipperary County Council has a statutory remit to maintain and protect the water quality status of rivers and works closely with Local Authority Waters Programme (Lawpro) on this matter,” a spokesperson for Tipperary County Council told the .

“The council does not have a remit for in-river works to remove natural vegetation and foliage, which are important for the biodiversity of the river and its ecosystem.

"In-river works to clear vegetation should only be carried out if there is a safety risk associated with it and only in conjunction and on approval by IFI [Inland Fisheries Ireland] and compliance with all statutory assessments.”

The maintenance of rivers was a “multi-agency approach and subject to appropriate consents being in place and assessments undertaken”, the spokesperson said.

For Mr Brennan and others — although not all Thurles residents agree, and many think the recent approach has improved biodiversity on the river — the comparison with other towns on the River Suir is odious in more ways than one.

Clonmel, Kilsheelan, and Carrick-on-Suir all benefit from the presence of the €6m Suir Blueway, which opened in 2019.

The blueway is a 21km riverside walking and cycling trail, and a further 32km of navigable water from Clonmel to Cahir, a town that capitalises on its heritage sites in the form of Cahir Castle and the OPW-managed Swiss Cottage.

In Thurles, Mr Brennan wants to see more and better river access, including a possible extension to the Watery Mall, and what he sees as a rebalancing of river health and management for human use.

“I just want a general clean-up,” he says. “If the water quality is good, it will grow back and be healthy.

“We don’t have to let every seed that drops into it left to grow and overtake the river bed. There just has to be a balance.

“There have been talks about extending the river walk, but it’s not exactly a tropical oasis down there at the moment: It’s full of cans and shopping trolleys and lads drinking. You don’t even see young people down there fishing anymore.”

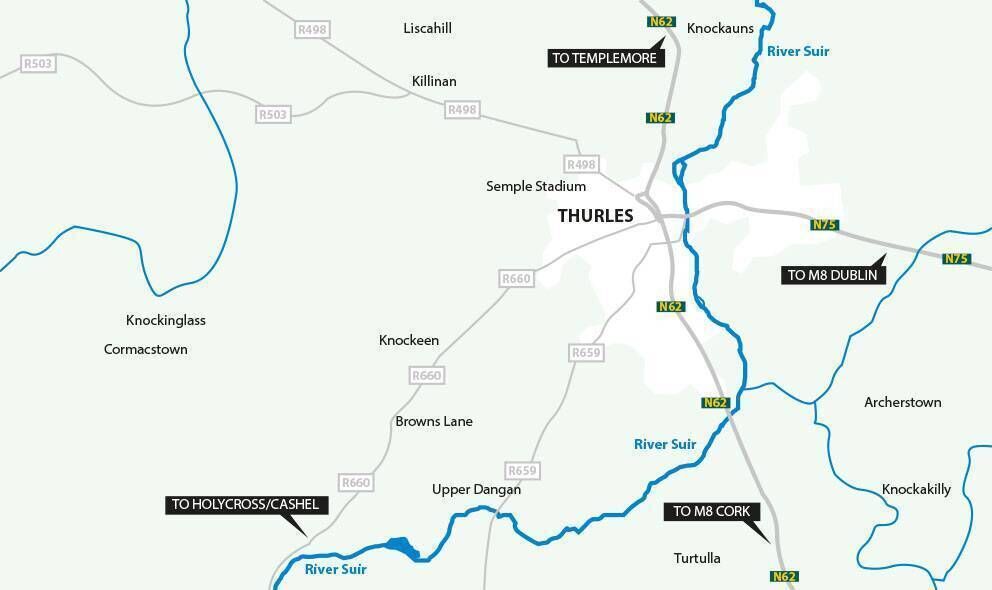

The Suir catchment area covers 3,610sq km mostly in counties Tipperary and Waterford. It flows out into the Atlantic Ocean at Waterford Harbour: It is one of the so-called Three Sisters, along with the Nore and Barrow, which it meets near Barrow Bridge on the border of Kilkenny and Wexford.

The River Suir is the third longest river in the country.

At 184km, it rises on the eastern flanks of Benduff, northwest of Templemore, and flows through Thurles, Holycross, Cahir, Clonmel and Carrick on Suir.

It then becomes tidal before continuing to Waterford.

It is known as one of the Three Sisters along with the rivers Nore and Barrow.

With an abundance of brown trout and salmon, the Suir is the record holder for a salmon caught from an Irish river, at 26kg in 1874. Salmon stocks have been dwindling in recent years.

The Suir is on the EPA’s list of catchments with the lowest percentage of rivers with ‘satisfactory’ water quality. Some 21 sites on the Suir were sampled in 2023, of which only eight were in satisfactory ecological condition.

Of its 131 river bodies, 62% are of ‘moderate or poor’ quality, while just three have ‘high’ water quality.

Tributaries including the Moyle, the Anner, and the majority of 12 sampling stations upstream from Cahir are in unsatisfactory condition.

The Suir faces the same kinds of pressures from human activities that are being found in all 46 Irish river catchments: Agriculture, habitat loss through development, forestry, urban waste water, and more.

Phosphates are a particular issue on the Suir. “Strongly increasing phosphate concentrations” were reported on its river sites in the EPA’s Water Quality in Ireland 2016-2021 report.

“Phosphorus loadings are mostly associated with pasture and urban wastewater discharges in the Suir,” the report concluded.

For one species in particular, these kinds of pressures amount to a threat that sees their very survival hanging by a thread.

On the River Clodiagh, which rises in the Comeragh Mountains and joins the Suir outside Portlaw, there is a population of freshwater pearl mussels that is at imminent risk of going extinct.

“Five years ago, scientists were saying that it would take 12 years for them to go extinct, so the clock really is ticking,” Paul O’Carroll says. “National Parks and Wildlife and various other experts in the field have carried out numerous studies and realised that the population is not recruiting itself.

“They are not creating young, because the habitat quality and the water quality is not good enough.”

Mr O’Carroll, who used to work as an environmental scientist with Waterford County Council, is now project lead with Friends of the Clodiagh River, a Lawpro-backed initiative that aims to stage a dramatic rescue and drive Margaritifera margaritifera, or the freshwater pearl mussel, back from the cliff edge of extinction.

The project has been going for five years, and involves two strands, Mr O’Carroll explains.

“The first strand is to take immediate action to save the population through a breeding programme, and the second is to make improvements in habitat and water quality, which is a longer term aim,” he says.

At the water treatment facility in Kilmeaden, Co Waterford, Mr O’Carroll has his tanks set up. With licencing permission, a cohort of the remaining adult pearl mussels were taken from the Clodiagh to form the backbone of a breeding programme.

Freshwater pearl mussels are involved in a delicate dance of life and death with the health of our rivers. Once so common on Irish rivers that they were fished for the treasured black pearls they produce, they are now under severe threat by declining water quality and habitat loss.

Freshwater pearl mussels can live up to 140 years. There are mussels still alive in Irish waters that have lived through the introduction of the motor car, the sinking of the Titanic, and both the Irish revolution and a revolution in farming that has in part led to their destruction.

Filter-feeding bivalves, each adult mussel will filter and clean up to 50 litres of water per day so they are important for maintaining water quality, but the juvenile mussels are incredibly vulnerable to both pollutants and changes in habitat, Mr O’Carroll explains.

“They need really high water and habitat quality,” he says.

As though they aren’t already fascinating enough, they also have a complex life cycle that includes a parasitic phase: They hitch a ride on the gills of salmonid fish — trout and salmon — for about nine months at the start of their life.

When the female mussel has eggs fertilised, she keeps them within her shell and releases them as tiny glochidia, up to 4m of them at a time. These glochidia must be inhaled by passing salmonids soon after their release, or they die.

At Mr O’Carroll’s breeding project, tanks of trout from the Clodiagh are also kept with the mussels in order to replicate this phase.

The mussels have such a delicate and complex life cycle and needs that, to date, the biggest success of the five-year breeding programme is to have raised juvenile mussels to about the nine-month stage.

For the initiative to work, they will need to raise the mussels until they are about five years old, while simultaneously working on the second strand of the project to improve Clodiagh water quality on enough of the river that the mussels have a habitat to go to.

It’s a remarkably high-stakes game. But Mr O’Carroll is remaining optimistic:

“We still have our population of adult mussels in the tanks and they are healthy, and are fertilising each other. We had a visit from a German scientist, and I think he thought we were getting a bit despondent.

"He told us, ‘look, the way these mussels breed, you only have to get lucky one year and you’ll have thousands of juveniles to return to the river. That’s the way they work: Keep going, and strike it lucky in one year’.”

Even if the breeding programme strikes the jackpot, though, there will have been little point unless there are pristine waters in the Clodiagh for the mussels to return to in five years.

Water quality on the Clodiagh has fluctuated wildly in the time for which the EPA has records available.

Unlike most river bodies, which show a slow, steady decline over time, the Clodiagh has gone from having 60% of its monitoring points unsatisfactory in 2007-2009 to having 80% ‘good’ waters in 2012-2015, to 20% high-quality waters — good enough for pearl mussels — materialising suddenly in 2013 2018, and back to no high-quality waters again in 2021.

The culprit, Mr O’Carroll is pretty sure, is agriculture. So he’s focusing the water quality improvement efforts on measures in farming in the area, with funding assistance from Lawpro, National Parks and Wildlife, and Leader funding.

“One of the issues for water quality is livestock access, so we’ve gone to three farms in the area and supplied solar pumps and fencing, so that the farmers can remove the river access from the cattle at no cost. It’s a small number of farmers but it’s a demonstration that they can take action to protect the river with minimal impacts on their farming.”

If the pearl mussel breeding programme doesn’t work, Mr O’Carroll says there will still be a net gain for ecology in the region: All improvements in water quality on Irish rivers are vitally important.

But he’s not giving up on the pearl mussels just yet.

“It’s very interesting work,” he says. “It’s slightly frustrating in that they are so sensitive: we don’t consider it’s going to be easy to achieve, but we are going to try.”

Read More

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB