Save our rivers: Anglers and allotment holders work together to defend the Boyne

The Boyne flowing beneath St Peters Bridge in Co Meath. Among the measures being undertaken by local conservationists is a plan to plant native trees along its banks. Picture: Gareth Chaney

In Athboy, Co Meath, a group has gathered around a brand new polytunnel at Athboy Community Allotments. The tunnel is empty, but one of those who have assembled is carrying an example of what the tunnel will soon be used to germinate — a one-year-old baby alder tree.

Ryan Wilson-Parr is one of the ecologists from Boyne Rivers Trust, a conservation group formed in October 2021 which works to rehabilitate the Boyne.

“This is just the first building block and we’ve been so lucky that the allotments have given us this area,” Mr Wilson-Parr says. “In time, this tunnel will be filled with young saplings and we’ll have an area outside for growing on the trees.”

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB

“This is our first tree nursery space. We are hoping to develop a network of sites throughout the county as community projects.

"We want people to volunteer, to collect seed from local sources in the catchment, grow it, pot it on and plant it.”

He gestures to the young alder he is carrying: “This tree, along with hopefully several thousand others, will be going into Jack’s land next year.”

Jack Rogers is another member of Boyne Rivers Trust, whose farmland nearby will serve as a pilot for an ambitious alluvial forest project the group is launching. In time, they aim to restore the Boyne catchment’s riparian — or riverside — vegetation by planting native tree species throughout the entire Boyne catchment.

“All the river woods in the Boyne catchment have disappeared,” Mr Wilson-Parr says.

"We have a tiny remnant of the original woodland left and the river’s ecosystem isn’t functioning as it should because we’ve lost so much biodiversity and tree cover.”

The Rivers Trust umbrella group began in the UK and now has 65 member organisations across England, Northern Ireland, and Ireland. The Boyne Rivers Trust is a relative newcomer.

The Boyne, which rises to the east of Edenderry and flows some 112km through towns including Trim, Navan, and Drogheda before entering the Irish Sea, is a river with fascinating mythology and heritage: The Salmon of Knowledge was said to be caught on the Boyne by Fionn Mac Cumhaill. Perhaps more tangibly, the Newgrange World Heritage Site is located in the Boyne Valley.

But the Boyne catchment is now fourth on the EPA’s list of most at-risk catchments.

Despite there being 10 special areas of conservation (SACs) in the Boyne catchment and it being a vital spawning ground for the increasingly threatened Atlantic salmon, there is just one river monitoring site of high quality on the Leinster Blackwater, the Boyne tributary near Kells, Co Meath.

Of 114 river waterbodies in the catchment, 51% are considered at risk of not meeting their Water Framework Directive objectives, according to the EPA’s last catchment report in May 2024. Of the river bodies in the catchment, 69% are of moderate or poor water quality.

Read More

So the battle for the Boyne is very real and very urgent. But what do trees have to do with water quality?

Tree root networks provide natural flood protection, improve water quality, and increase biodiversity, Mr Wilson-Parr explains. And tree cover along river banks provides another climate future-proofing benefit: Their shade cools the water temperature.

“We have a bigger problem in that water temperatures within the catchment are getting higher, so a lot of parts of the river are now inhospitable to Atlantic Salmon in the summertime,” Mr Wilson-Parr says.

“The Atlantic salmon population has itself declined by almost 80% over the last 30-40 years, so that alone is reason to really get behind this initiative.”

The Boyne Rivers trust native alluvial woodlands project has been funded by Lawpro, the Local Authority Waters Programme. The Boyne has been selected as one of five catchments across the country piloting a proposed catchment management plan process coordinated by Lawpro in 2024.

The River Boyne is a river in Leinster, the course of which is about 112km long.

It rises at Trinity Well, Newberry Hall, near Carbury, Co Kildare, and flows towards the northeast through Co Meath to reach the Irish Sea between Mornington, Co Meath, and Baltray, Co Louth.

The River Boyne and its tributaries comprise about 530km of river channel and drain an area of 1,040sq miles. This river is one of the country’s premium brown trout angling waters offering superb fishing to the visiting angler.

In the spring of the same year the Boyne Rivers Trust was founded, Dawn Meats’ Navan plant applied for planning permission to Meath County Council for a 7.2km pipe to discharge 400,000 litres of treated effluent from their abattoir into the Boyne per day.

There was public outcry.

A group called Save the Boyne was formed, and hundreds of residents, kayaking and angling groups, and local representatives submitted objections to the plan. Even 007 himself weighed in, with Pierce Brosnan, who was born in Navan, recording a video appeal for Save the Boyne.

Nevertheless, Meath County Council granted planning permission for the controversial scheme in April 2022, and the local authority’s decision was appealed to An Bord Pleanála by Save the Boyne and others.

An Bord Pleanála turned down a request to hold a public oral hearing. Although a decision was due by September 2022, no inspector’s report has been made public and there has been no decision.

While Boyne Rivers Trust as a group does not currently engage in advocacy work such as planning objections, for some individual members, the experience of the Dawn Meats application was something of a catalyst: People sat up and really paid attention to water quality on the Boyne.

“I would have been very activated by that, and it did activate a lot of people,” Jack Rogers says.

One of the Boyne Rivers Trust’s aims is to promote community connections to the water, and higher interest and custodianship as a result.

For David Bebb, secretary of Athboy Community Allotments — where the Boyne Rivers Trust Native Alluvial Woodlands project is about to take root — the knock-on impacts for allotment holders could be profound.

“We are a small community concern, but to be involved in something that is going to have such a significant impact on the Boyne catchment is something we’re very proud to be involved in,” he says with enthusiasm.

“We’re 20 allotment holders here, just growing our veg and potatoes and flowers: We are potentially having a major impact on restoring the Boyne.”

The Boyne’s reputation as a salmon river is the stuff of lore. The magnificent migratory fish come up from the sea, through the estuary, and far into its streams and tributaries every winter to spawn.

So when the river is under threat, so too is its role as the birthplace of the King of Fish. Atlantic salmon stocks have been decimated globally by everything from commercial over-fishing to hydromorphology in the form of weirs and dams on their migratory path, to fish farms with a deadly lice burden.

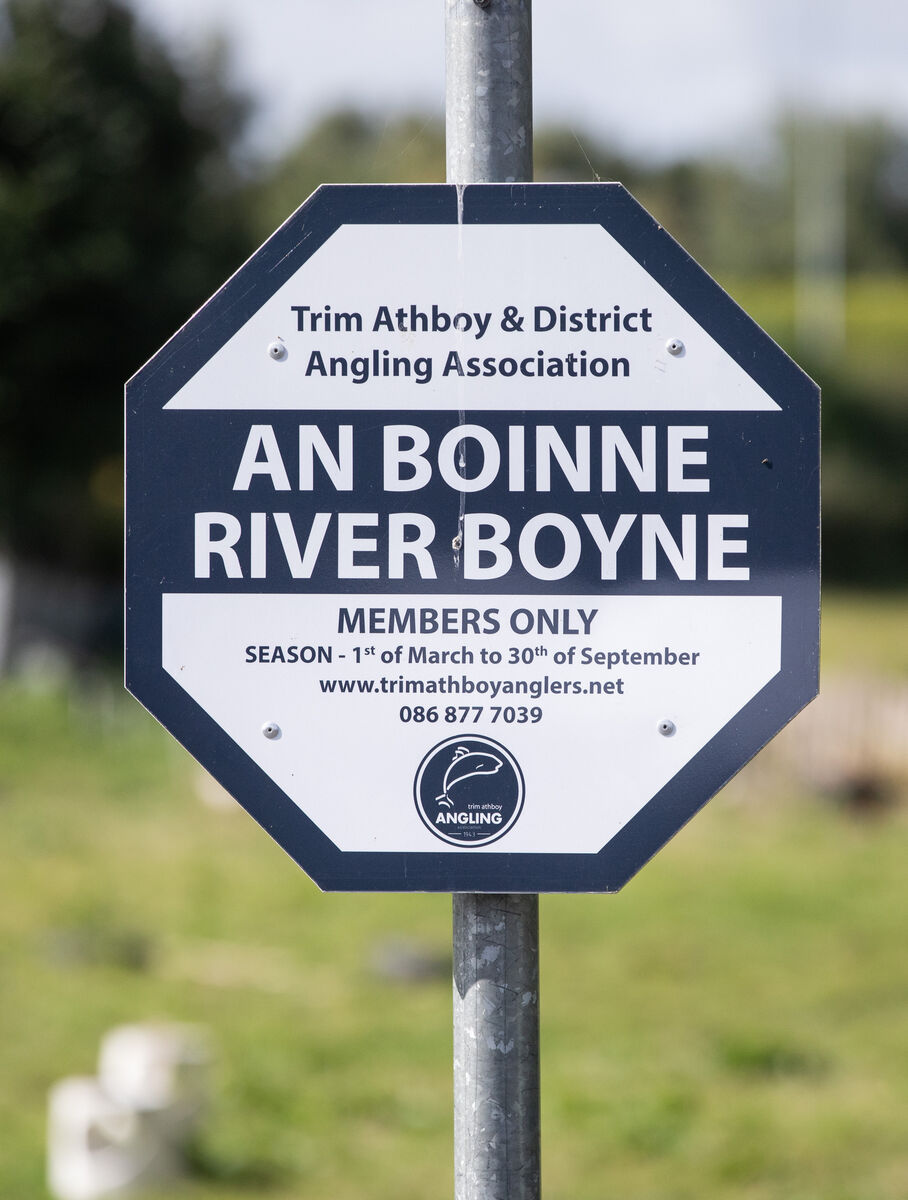

Pat O’Toole of Trim Athboy & District Angling Association has a plaque on the wall of his house outside Trim with his prize salmon, a whopping 23-pounder, on it. Look closely, though, and you’ll see that this is a replica rather than a real stuffed fish: Since the Boyne went catch and release 18 years ago, the replica is an acceptable memento and the live fish gets returned to the river after its epic battle.

Mr O’Toole has fished on the Boyne for 63 of his 69 years and often fishes overseas in Canada, Iceland, or even Argentina. In the winter, he walks along the tributaries of the Boyne, observing the salmon spawning.

He’s been involved in conservation actions for a long time, including protests to prevent netting the migrating salmon on their way up to spawn, a practice that was stopped eventually 18 years ago, at the same time that the anglers agreed to go catch and release.

But he says the problems started far earlier, when the Boyne and its tributaries were dredged as a form of flood relief, beginning in 1960s and ending in 1986.

“These were all the main salmon spawning grounds,” he says with a disbelieving shake of his head. “And a lot of the gravel was just taken out and dumped on the bank. It was never rehabilitated.”

Atlantic Salmon may be just one species, but their presence since ancient times has been connected to the health of Irish rivers: Their fry are a food source for a vast range of other species.

Mr O’Toole was one of the people who made a submission against the Dawn Meats abattoir effluent application. He says the area below the proposed discharge pipe is already under pressure — he filmed video of algal bloom in the river near Slane last year — and that if anything were to go wrong with the treatment of the discharged effluent, salmon would be affected.

“Below that pipe, the salmon come into the river and if the water is low, the salmon hold in pool below where the pipe is meant to go,” he says.

Although Dawn Meats argue that their plan is an environmental improvement — currently their waste water is tanked offsite to a waste water treatment facility, and their plans contain extensive upgrades to their onsite waste water treatment — Mr O’Toole does not agree.

“If the water was going to be that pure coming out of the plant, why do they need to discharge it at all?” he says. “Why can’t they store it and reuse the water?”

Agriculture is the top significant pressure impacting 66% of the at-risk waterbodies within the Boyne catchment, followed by 39% impacted by hydromorphological pressures and 16% by domestic wastewater.

But waste water is an area of major concern to the anglers who say the waste water treatment capacity in the area is not fit for purpose when it comes to the rate of housing development and new homes in what is now Dublin’s commuter belt.

They have particular concerns in nearby Kells. It is unsustainable population growth unless the infrastructure can support it, they say. Mr O'Toole says:

"They’re just going to build more and more houses and more. And once the river is gone, it’s gone.”

Out on the river, Mr O’Toole wants to display several sites where the anglers have worked with Inland Fisheries Ireland’s (IFI) local representatives and the OPW on a form of river rehabilitation they say will help the recovery of the Atlantic salmon. He’s wary of naming some of the tributaries visited for fear of poachers, but he shows the three areas that have been, or are in the process of being, re-gravelled.

As silt from human activities — including farming, road and construction runoff, forestry, and waste water treatment — enters the water, it settles in the gravel beds the salmon need for spawning and calcifies into a hard surface, he explains.

Salmon rely heavily on loose gravel beds for their very survival. Female salmon use their tails to create a nest called a redd to lay their eggs while spawning. After the eggs hatch into tiny alevins, in this crucial stage in the salmon’s life cycle, they hide in the gravel around where they hatched.

In 2018, the anglers worked with the IFI and OPW to put 16 lorryloads of fresh gravel into the Boyne near Trim.

Although the approach has its detractors and not all ecologists think that disturbing the river to such an extent is a good idea, Mr O’Toole says the fry count, literally the number of baby salmon you can count in the water, proves the success of the re-gravelling scheme. He says:

Mr O’Toole and his fellow anglers want to see a regular programme of re-gravelling on the tributaries that the salmon use. The anglers feel that providing this spawning habitat plays a vital role in reversing salmon stock decline.

“We can do nothing about what’s happening to them at sea. What we can do, it’s what’s here in the river,” he says. “If you don’t have the maternity up here, you don’t have the salmon. All we can do is look after the spawning streams, which are the most natural hatcheries you’ll ever have.”

At another site, works are ongoing in agreement with the landowner. Mr O’Toole shows a third site, which was re-gravelled last year, as well as being fenced against livestock to create a riparian zone, funded by a salmon conservation fund that comes out of the anglers’ river licences.

The water is sparkling clear, with young fish of different species darting amongst a variety of aquatic plants. Mr O’Toole surveys the scene with satisfaction.

If it weren’t for the human activities that are causing silting, the river wouldn’t need these works, he agrees.

“Well, you can’t control everything that’s happening, but there’s two ways you can go: You can do nothing, or you can do something,” he says. “I walk these rivers all the time in the winter, and there was spawning in every place I went to. So that leaves me very optimistic.

“As long as the work is done, we can protect it. There’s no further place than here: This is the very beginning for the salmon. If the farmers keep working with the fishery board, it’s a win-win for everyone.”

Read More

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB