Make woodlands and wetlands count — our future literally depends on them

Greater Spotted Woodpecker: When these birds lost their hold in Ireland, during the 17th and 18th centuries, it was likely due to the widespread loss of woodland here. Now they have come back and are spreading westward year by year

One of the most wonderful places to be at this time of year is being enveloped in layers of a deciduous woodland.

As April rolls in, camouflaged woodcock are courting — males dancing to impress while females find a place among the soft wet mud of a woodland floor to nest.

Bright white star-shaped flowers of wood anemone spill out over tangle of twigs and last year’s fallen leaves, and taller heads of wild garlic and three-cornered leek fill the woods with their rich distinctive scent.

Tree creepers' feathers are also perfectly discreet against the mottled bark of oak and ash, allowing these little birds to remain unseen as they walk vertically up trees tree trunks, using their finely sculpted slender beak to pick small invertebrates from tree trunk fissures.

In some places, greater spotted woodpeckers can be heard already, drumming on old tree trunks high up in the canopy. With built-in shock-absorbers in their skull, woodpeckers are able to use their beak to hammer into wood, excavating nest holes high up in the treetops.

When these stunning little birds lost their hold in Ireland, during the 17th and 18th centuries, it was likely due to the widespread loss of woodland here. Now they have come back and are spreading westward year by year.

IPCC's Synthesis Report is out now!

— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) March 22, 2023

Why is it important?

The report integrates findings from 6 reports during IPCC’s sixth cycle. It provides a complete picture of #climatechange & the solutions we have available to address it. https://t.co/zAMzd12lR7https://t.co/EFCQOEb56b pic.twitter.com/NMEHWGx5ue

But outside the cosy luscious layers of a deciduous woodland in spring, we are faced with the harsh reality of all that we lack in terms of woodland cover in Ireland.

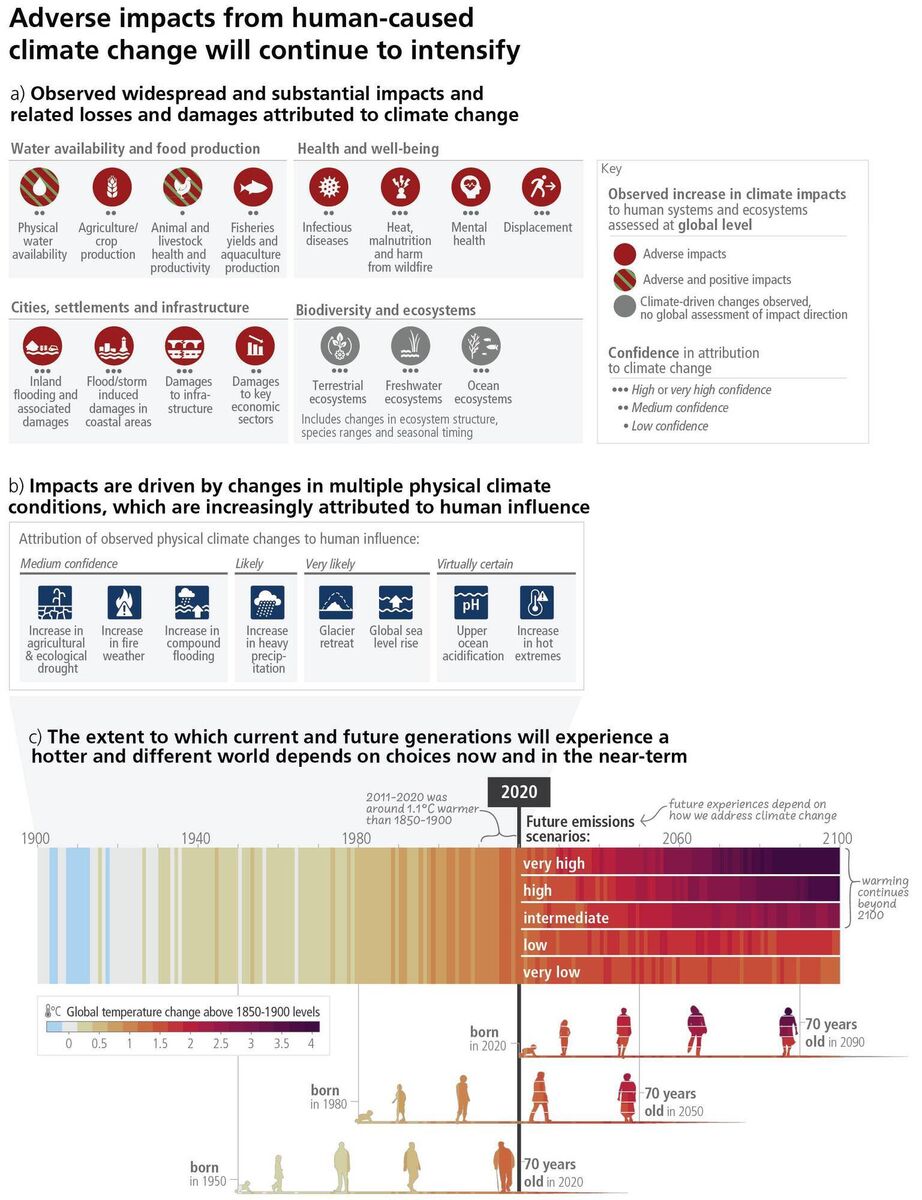

Last week the IPCC published its most powerful climate report to date, in which scientists from across continents and disciplines are urging the world to reduce climate pollution by two-thirds in just 12 years if we are to have any chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The scale of destruction and loss that climate chaos is already having on so many across the world is a very loud wake-up-call, requiring action by each and every one of us and each and every sector of society.

Hitting the snooze button again will eliminate whole swathes of currently liveable landscapes for billions of future humans as well as millions of wild creatures. Upon the release of this latest IPCC synthesis report, UN secretary general, António Guterres, said:

This is where we look to the natural environment for solutions. Ending all fossil fuel extraction without further delay is only one of the measures so urgently needed. Living ecosystems are our greatest asset in diffusing the ticking time bomb of climate chaos.

I have written much written here before about restoring peatlands (oct 2022). But the planting of trees as a climate action is often poorly understood.

There is an assumption that all tree planting is good for fighting climate change, but this is not the case.

Forestry is important for carbon sequestration but only when the end use of wood is accounted for. We know, with decades of detailed research, that forest management is often destructive to wildlife and water quality.

We know now too, that there are far better ways to plant and manage forests, approaches that store and sequester far more carbon than conventional plantations.

Meanwhile, carbon from Irish soils, especially peat bogs and other wetlands, is currently a net source of greenhouse emissions to the atmosphere. This is a result of peat-rich soils having been drained in the past decades for agriculture and forestry.

Drained peatlands and related activities account for emissions of some 11 million tonnes of CO2 per year in Ireland. Carbon sinks from forestry only remove about 3.6 Million tonnes.

The land use emissions are rarely acknowledged or factored in official figures, yet the sequestration from forests is carefully counted and proclaimed.

In addition, there are currently more than 300,000 hectares of forested peatland across the country, many of which are continually leaking greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere.

Yet State-supported forestry ploughs on with plantations of spruce while only a fraction of the financial support is allocated to restoring and rewetting peatlands, including removing forest plantations from drained peat soils.

If the Government and the forest sector is serious about changing land use practice to sequester carbon they’d be embarking on an ambitious programme of peatland restoration and rewetting and conversion of forest plantations to continuous cover forestry. Such actions offer far greater gains, in climate terms alone, than more plantation forests.

Massive incentives and supports are needed instead for conservation and expansion of native woodlands, as well as converting spruce plantations to continuous cover forest systems.

‘Continuous cover forestry’ offers both direct commercial gain as well as valuable ecosystem services, because high-quality timber is extracted on a selective basis, while the canopy, and most importantly the root systems are all left in place.

In a woodland, the bulk of carbon stores exists beneath the ground, where tree roots and carbon-rich woodland soils store carbon on an ongoing basis. This is what makes continuous cover forestry so much more effective at storing carbon in the long term than clear-fell systems that currently dominate forestry in Ireland.

Permanent forests and woodlands are also far more effective in climate adaptation, making entire landscapes more resilient to impacts such as floods and droughts. Because these woodlands contain a mix of many tree species, most of which are native, they are more resistant to pests, droughts, and fires.

Nature-based solutions such as these are where we need to turn in these times of climate crisis. If we are to listen, and act upon this stark wake-up call of the IPCC, much would be done to redress the imbalance of profit over liveable futures. Like the return of woodpeckers to Irish woodlands, nature has an innate ability to bounce back.

Now more than ever, we need to treat woodlands and wetlands as though our future depends on them — because, in fact, it does.

- Anja Murray’s new book, , is available now. Follow Anja on twitter @miseanja

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB