Terry Prone: Like others with dementia, Bruce Willis is being robbed of his dignity and privacy

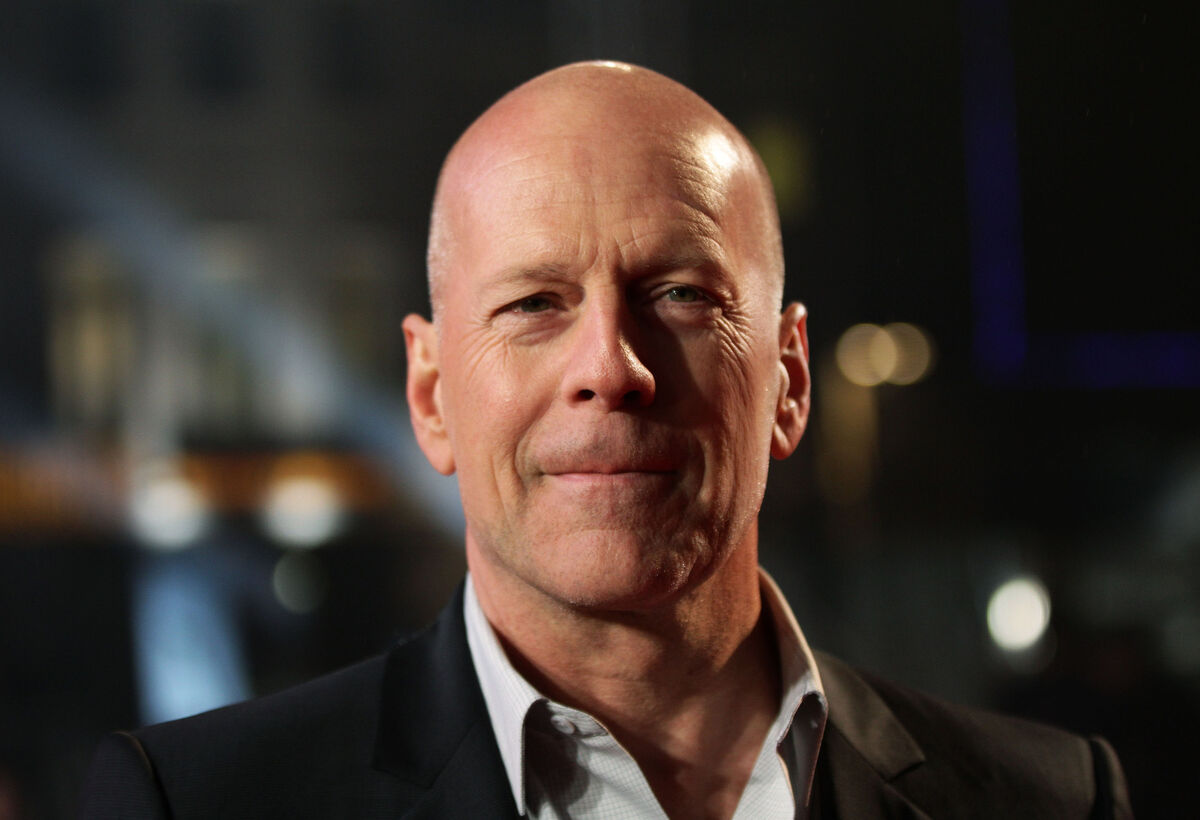

Having been diagnosed with dementia two years ago, the private circumstances of Bruce Willis’s deteriorating condition are now being publicised by members of his family. Picture: Instagram

I'm for calling it the Bruce Willis Syndrome.

The Bruce Willis Syndrome describes a 21st century activity: Friends and families of famous people suffering from dementia sharing pictures and stories about their decline. All in the name of love.

Oh, yes, it’s love that motivates those around the demented person to tell all about them. Of course it is. What else could motivate them? Money? Fame? Likes? Oh, shush that cynicism.

Bruce Willis developed a neurological deficit (to put it in a measured way) just a few years ago. He ceased to be what used to be what we used to call “the full shilling”. But he continued to work, turning up on film sets where the other professionals had been warned that it might be a good idea to get his bit done and dusted before lunch.

Dozens of actors, make-up artists, gaffers, and others watching him speedily worked out that something was very wrong with the actor, and further realised that it was a whole lot more than a reduced ability to learn lines. That latter was coped with by fitting Willis with what’s known in the trade as an ‘earwig’ — a device inserted into his ear allowing someone to articulate the next bit of dialogue he was supposed to utter.

Variations of this kind of device have always existed to serve actors who were old, alcoholic, or who simply couldn’t be arsed learning the script.

John Lithgow, who plays Dumbledore in the HBO series based on the Harry Potter books, has within recent weeks been photographed on set in full costume, emoting with poster-sized prompt cards in his eyeline.

So what could be wrong with deploying an ‘earwig’ to help Willis out?

Let’s go back to the dozens of professionals who observed and later commented on the actor’s cognitive diminution during his last few films. He didn’t seem to know where he was or why he was there, saying to two people working with him on one production that he knew why they were present, but not why he was present. None of the banter expected between performers who had worked together before happened between scenes. In fact, no conversation happened at all. Nothing.

Despite how obvious the deterioration, during these years the man participated (“acted” might be stretching the point) in as many as six movies characterised by such low standards and small budgets that his puppeted performances didn’t stand out that badly in the mix.

Plus he was paid $1m a day. Might not have made any difference to a man losing the capacity to talk, never mind count, but it made a difference to those around him.

Putting a positive slant on it, let’s imagine that his extended family figured the extra $40m or $50m would come in handy to fund care as his condition deteriorated. To which the answer has to be profane dismissal.

He had already earned more than he could ever spend and anyone committed to his reputation would have kept him at home and not risked his reputation by allowing him to be part of shamefully bad films.

But then, an even worse aspect of the Bruce Willis Syndrome kicked in.

Announcements were made by his family about him suffering from aphasia. More announcements followed, explaining his dementia.

Willis had no agency. No dignity.

Even though earlier dementia sufferers, like Ronald Reagan, issued the initial communique while some of their brain cells were still functioning.

Of course, Willis may have deteriorated, during the time spent “working” on terrible movies, beyond the point at which he might have had any capacity to contribute to any public statement.

Then came the photographs of him. Photographs of that marvellous smile as he’s hugged by children and grandchildren. Then, in that splendid social media phrase, the wife and the ex-wife “broke their silence” (which tends to be of a day or two’s duration) to share their love and care for the diminished man.

They continued to break their silence, in the current wife’s case in the form of a book about their situation.

That’s how it works.

Fame does not protect from the basic reality that the person with dementia is the loser.

Once diagnosed, they lose all of their rights, starting with the right to privacy. Contrariwise, the people around them gain total power. And — the more they invade and exploit the demented person — paradoxically, the more power and public credibility they gain.

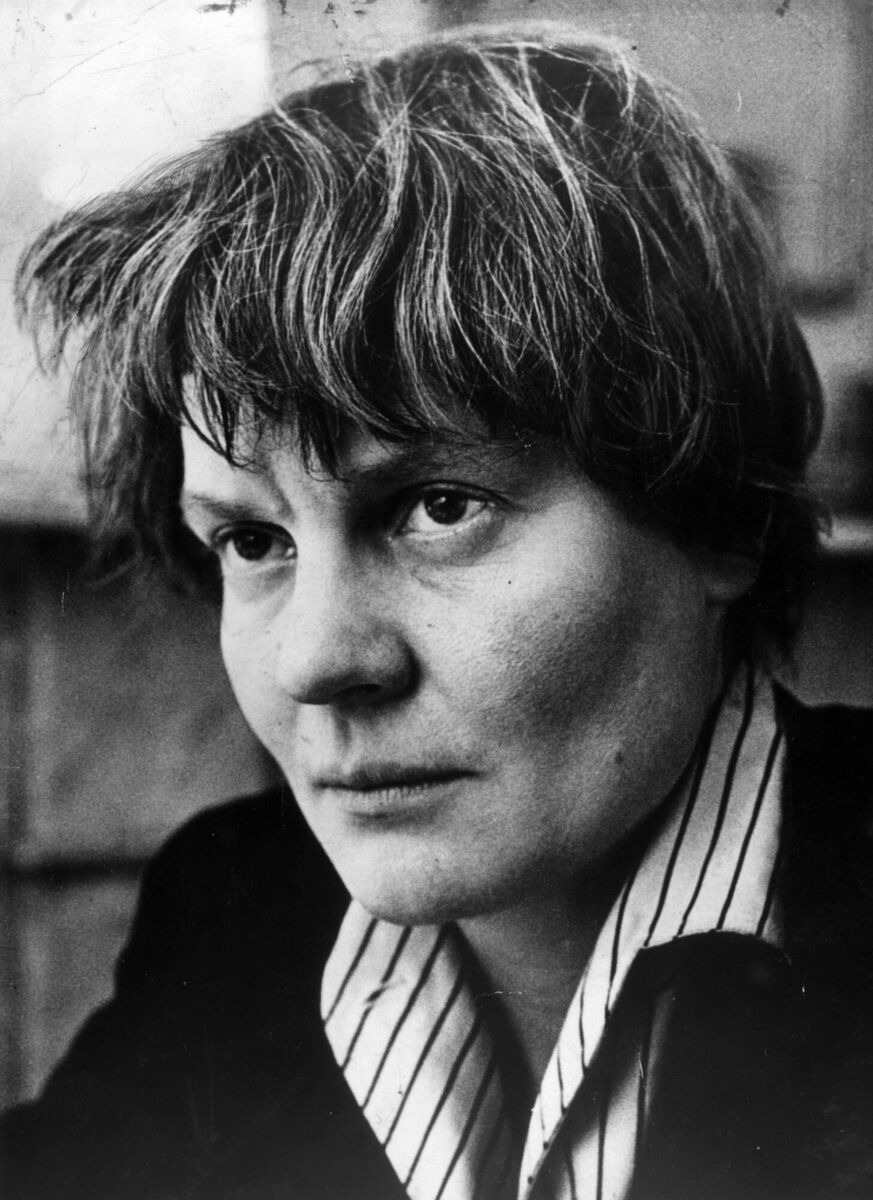

The early definitive example was Iris Murdoch’s husband, John Bayley. Now, Murdoch had been repeatedly unfaithful to Bayley during their lengthy marriage. But they stayed together, which made Bayley the first witness to Murdoch’s Alzheimer’s disease.

He was her carer.

While caring for her, he watched her and made notes which eventuated in a bestselling memoir, published as Elegy for Iris.

That memoir was the ultimate revenge for her infidelity, recording, as it did, in grievous detail the physical and mental destruction of a formidable human and recounting her involuntary retreat from the behaviours we associate with civilised living.

For more than a decade, Bayley lived financially off the memoir, praised on all sides for its honesty. It was a valedictory tour of literary events, with the memoirist permanently aglow in plaudits.

Since then, the Bayleys of this world have proliferated, with one partner or spouse after another honestly telling the stories of the demented person’s violence, roaming, or random urination/defecation. The honesty of the accounts tends to be excused on the basis that it is delivered “with such love”.

Where is the love in shaming someone you claim as your nearest and dearest? Who gains from this? And don’t — please don’t — advance the spurious nonsense that hearing about your partner’s incontinence will make some stranger feel better about their partner’s incontinence.

Sharing shameful details about a demented spouse, partner, parent, or sibling is never done with their permission. Any decent spouse, parent, sibling, or friend who had the prescience to ask the relevant question before cognitive decline set in would get a right quick answer.

Imagine the encounter.

If Dervla still has her wits about her, the simple answer is “Are you out of your mind, you disgusting creep, how could you think for even a split second that I would be anything but horrified at the prospect of you sharing something so private, so diminishing of me with any third party?”

The more complex answer would be for Dervla to leave the other individual, right then, because no relationship would sustain the articulated prospect of such a betrayal.

Yet it constantly happens, this betrayal by people who, in the name of love, share what the beloved would never have permitted them to share if they had not been felled by dementia.