Terry Prone: Sorry state of some sculptures a reminder in how not to memorialise people

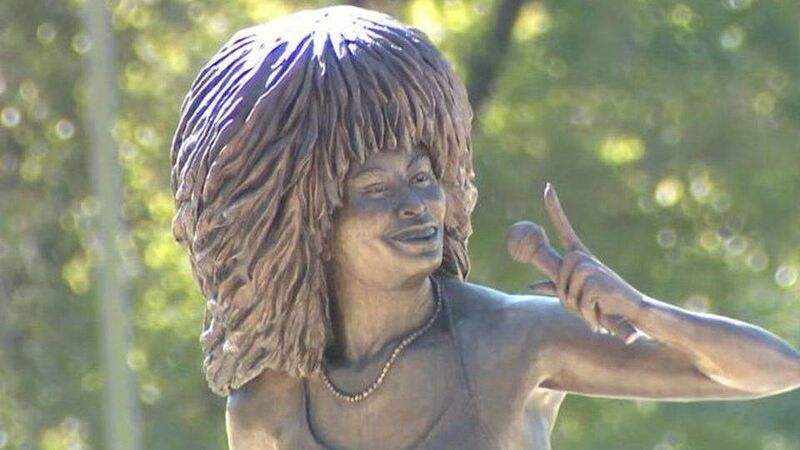

The new Tina Turner statue by Fred Ajanogha.

As the train slowed on its way into Houston Station, the two young American tourists opposite spotted a tall thin structure out the window and wondered what it was. It was like all my Christmasses had come together. Not only did I know a thing, but I had two customers for the thing I knew.

“It’s the Wellington monument,” I told them. “Tallest obelisk in Europe.” They thanked me politely, and a silence fell while I wondered if I was right about it being the tallest in Europe. After a couple of minutes the younger guy drew a deep breath.

“Wellington?” he asked.

Lock, stock and barrel, I gave them Wellington, right down to his comment about the Battle of Waterloo after he’d won it: "Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won."

“Are you a professor?” the other one asked me. I wanted to take him home with me, I was so chuffed. I denied it, but didn’t tell him that the only reason I knew this stuff was because at 13 I had read Georgette Heyer’s historical novel about Waterloo and had it — and Wellington — imprinted on my memory.

As we walked towards the ticket-checking machines which mostly rise above their task, forcing everybody to exit through one permanently open slot, I could hear one of the two Americans suggesting to the other that it was kind of a pity the memorial was an obelisk and not a statue, since the latter would give you some idea of what Wellington looked like. Even that far back, there had to have been pictures of the general.

“He had a horse, too,” the younger one confirmed, reading off his phone. “A chestnut stallion named Copenhagen. He rode him for 17 hours during that battle.”

These two had the slightly southern accents that bespoke growing up in areas where the local courthouse always had a statue out front of a mounted officer, usually Confederate. Now, Wellington was good on a horse (Copenhagen lived in retirement until he snuffed it at 28, so it doesn’t look like Waterloo left him with equine PTSD.)

But in the old days, if you asked a search engine to give you cartoons of Wellington from the time, they would offer you the works of lads like Cruikshank, featuring Wellington, his Roman nose and — much more prominently — a cannon protruding from between his thighs as if it was an enormous penis. We may think that social media comment these days is pretty vicious, but you don’t often see a celeb’s reputation for virility illustrated using a weapon of war. Wellington was not a man to hold back when it came to sex, and the cartoonists around him had a great time being figurative about it.

Before any readers of the start activating their AI servants to take a quick gander at Wellington astride the cannon, the bad news is that search engines have gone proper puritanical and instead of providing the illustrations with which they were remarkably free just two or three years ago, now give you a lecture about not providing you with pornographic material. Idiotically, they even go further, offering to work up an illustration of Wellington standing beside a cannon. I kid you not.

It didn’t seem the right time to catch up with the two young Americans to tell them that maybe the obelisk was safer, since an early nineteenth century sculptor seeking to render a truthful version of the general hadn’t much choice between Copenhagen and a cannon. At least you can get inside the obelisk and get a marvellous view from the top, not to mention observe the swinging yoke that lets you know how much the things sways.

Brownsville, Tennessee where the late Tina Turner came from, might have done better to go the obelisk route rather than the ten-foot-high statue of the singer which, as of last week, dominates a public park there. Note the use of the word “dominate” rather than “decorate” because the latter it seriously doesn’t do.

“Simply the worst,” was the easy but effective verdict of official and unofficial critics alike after the unveiling of the new Tina Turner statue by Fred Ajanogha that makes her look like a thatched cottage in a miniskirt.

“When making this statue, I tried to capture three things: her flexibility and her movement — then on her hair, I wanted it to be like a mane of a lion, to represent her strength as a woman,” Mr Ajanogha said in a statement. “Lastly, her hand holding the microphone — there is one finger held up. I used that to represent that there is only one Tina Turner.”

It’s often assumed that advice to the effect that when you’re explaining you’re losing applies only to politicians, but it applies with bells on to sculptors, too. Mr Ajanogha, right now, is famous for the wrong thing. He’s the new version of Portugal’s Emanuel Jorge da Silva Santos, who may have a more resonant name, but who shares Fred’s incapacity to create a statue that looks remotely like its subject, in Emanuel’s case footballer Cristiano Ronaldo. They’re both up there with the sculptor Dave Poulin, who thirteen years ago provided a statue to a New York park memorialising actor Lucille Ball which not only didn’t look like her, it didn’t look like anyone, ever. It was quickly dubbed Scary Lucy and eventually replaced with a statue which looked very like the character from I Love Lucy, proving that it’s not actually that difficult to produce a bronze version of a distinctive famous person.

It never has been. The portrait of Oliver Goldsmith created in the nineteenth century by Joshua Reynolds indubitably evokes precisely the same man who stands in bronze outside the front door of Trinity College. In those days, sculptors had only live sitters or portraits to go on, but they produced the goods. As did a later generation of sculptors: the statue in Dublin of the child molesting and generally appalling human William Smith O’Brien, when you get past the arrogantly folded arms, has a face that’s pretty close to the one in mid-nineteenth century photographs of him.

The man who created the Tina Turner abomination didn’t have to rely on a portrait or a black and white photograph. Fred would have had literally countless still and moving pictures of the singer at his disposal. And yet he couldn’t come up with something that looks like her and was reduced to telling us about the symbolism of the unmoving singular finger.

No doubt Fred, Dave and Emanuel would protest that while a computer could generate a hologram that would match the famous subject precisely, their job as artists was not simply to copy reality, but to evoke the essence, to take observers past accuracy into imaginative discourse with the statue.

Not buying that, lads. Ye’d all have been better off producing an obelisk.