Colm O'Gorman: I admired Pope Francis — but we must be honest about his failings

Pope Francis making his way to the altar to celebrate Mass at the Phoenix Park in Dublin in 2018, when he asked for forgiveness for abuses in Ireland — but Colm O’Gorman argues that the cover-up of abuses has always come from the Vatican itself. Picture: Dan Linehan/Irish Examiner Archive

I have come to realise that the greatest barrier to the honest acknowledgement of the scale and deliberate nature of the global cover of clerical sexual abuse is not the struggle to uncover the truth, but rather our collective inability to believe it.

We know the truth. It is now indisputable that the cover-up of the rape and abuse of hundreds of thousands of children and vulnerable adults by Roman Catholic clergy was mandated and directed by the Vatican at the highest level.

We know that senior clergy, bishops, cardinals, and indeed popes have lied about that cover-up and their role in directing it.

We know this because it has been proven by state investigations across many jurisdictions, and by revelations forced by campaigners and activists, ourselves the victims of clerical sexual abuse.

In 2006 I made a documentary for the BBC, . The film explored the central role played by the Vatican in the cover-up of child sexual abuse in Ireland, the US, and Brazil.

The film also focused on a 1962 Vatican directive sent to every Roman Catholic bishop in the world, which set out the procedures to be used in cases of clerical sexual abuse.

It required the establishment of internal Church investigations which swore victims, alleged perpetrators, witness, and investigators to pontifical secrecy.

It enforced absolute secrecy, any breach of which would result in excommunication. It directed the cover-up.

When the film aired, it was roundly attacked by Church authorities.

They said that the film was “false and entirely misleading”. They insisted that the document revealed in the film had nothing to do with child sexual abuse by clergy, insisting that it dealt solely with cases of clergy soliciting sex in the confessional.

That was a lie of course, another example of Catholic Church leaders using obfuscation and blatant deceit to deflect from the truth and from any measure of public accountability.

Proof of that came a full 13 years later, in 2019, when Pope Francis finally abolished the use of the “pontifical secret” as proscribed in the directive in clerical sex abuse cases.

I could point to a multitude of other examples of deflection and deceit by senior Catholic Church figures.

From the mid-1990s on as countless cases of abuse began to be revealed, Church leaders, popes included, first denied that the allegations were true, labelled accusers as liars, and asserted that the revelations were part of a media conspiracy against the Church.

When that position became untenable, they told us that these were cases of a few bad apples, of the corruption of Western society which had now infected even the priesthood.

This despite the fact that the Church has had procedures in place to address sexual crimes by clergy for centuries. The first laws were introduced in the early fourth century. The 1962 directive revealed in our documentary was itself a refresh of an earlier document issued by the Vatican in 1922.

Church history is littered with examples of efforts to address, or cover up, sexual crimes perpetrated by clergy.

The revelation of these crimes may have been shocking to wider society, but they were no surprise to the Vatican.

Sometimes I think that the lies told are so blatant, so extreme, that we struggle to recognise them as lies. It is too much to wrap our minds around. We were able to accept in time that the abuse happened. And then we eventually accepted that it was covered up by bishops.

It still seems, though, that we cannot acknowledge that the Vatican itself mandated that cover-up and has consistently lied about it.

The Vatican has acknowledged that bishops had mishandled cases of abuse. Popes have expressed regret and sadness at the suffering caused by the actions of some priests and the failings of Church officials. Their statements were breathlessly reported as groundbreaking apologies.

They were nothing of the sort.

When I was five, I made my First Confession.

I remember learning that if I hurt another person by my actions or failures to act, I must acknowledge my failure, take responsibility for it, apologise, and seek forgiveness. I learnt that an apology required an honest admission of responsibility.

No pope, not even Pope Francis, has apologised for the cover-up and for the Vatican’s facilitation of the rape and abuse of countless children and vulnerable adults.

Pope Francis did go further than his predecessors. He spoke of the shame he felt at “the incapacity of the church” to show sufficient concern for victims of abuse. He acknowledged some personal failings as well, though he spoke in rather general terms and never seemed to address the specifics.

Sadly though, he repeated many of the failings of his predecessors.

When Pope Francis visited Ireland in 2018, the Vatican had to be forced to abandon its insistence that the visit would not address the abuse scandals, and that the Pope would not meet with survivors of abuse while he was here.

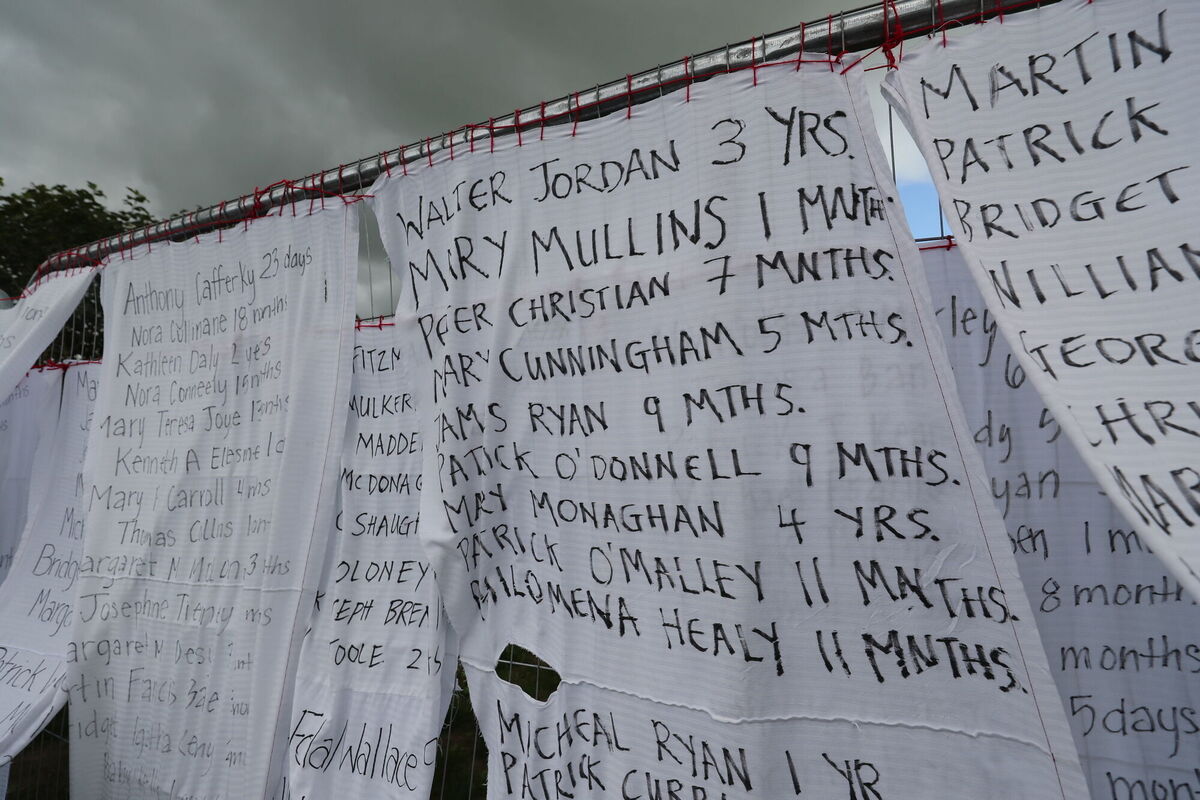

In the end he did meet with survivors, including former residents of Church-run institutions, Magdalene laundries, and mother and baby homes.

Those who met with him spoke of his shock and distress at hearing their stories.

They also reported that the Pope was “taken aback” and “shocked” upon hearing about mother and baby homes during the meeting and had “no idea” what a Magdalene laundry was.

If Pope Francis did say this — and I accept the word of those present that he did so — then it was a deceit.

Francis knew what a Magdalene laundry was and he knew about mother and baby homes. As pope, he would have been made aware of the scandals in Ireland.

He had access to the Ferns, Murphy, Ryan, and Cloyne reports.

To the McAleese review into Magdalene laundries, and to all records and reports about the atrocities committed in mother and baby homes in Ireland.

He would have known that the Vatican had repeatedly refused to co-operate with State inquiries into abuse here in Ireland. His officials would have briefed him about all of this in advance of the visit, even if he had not proactively sought out that information himself.

And lastly, we know that Francis was well informed about mother and baby homes because he met with campaigner Philomena Lee and writer and actor Steve Coogan following a screening of the film in Rome in 2014.

In the days since the death of Pope Francis, it seems that we are rewriting history somewhat. Many, including Government leaders, have praised Francis’ response to the abuse scandals.

I understand why so many people want to remember the goodness of the late Pope. I greatly admired Pope Francis in many ways. His humanity and decency were obvious in not just his words but in his deeds.

His leadership at a time of public and political polarisation and conflict was hugely important.

We can and should remember his goodness, but if we are to speak about his response to abuse, then we must also be honest about his failings.

We cannot perpetuate the lie. No matter how uncomfortable it might be, the truth matters. Moments like this are how history is recorded.

I am not confident that any pope will ever tell the truth about the cover-up of child abuse within the church. Which makes it even more important that we do so.

The endemic abuse that was permitted and then covered up by the Roman Catholic Church at its most senior levels has done incalculable harm to countless numbers of people globally.

The very least we are due is the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it might be. The truth matters. It is a key element of delivering justice for victims of abuse, and of preventing such abuse in the future.

- Colm O’Gorman is a survivor of child sexual abuse and a founder of the charity One in Four