Doctor fatigue puts patient safety at risk

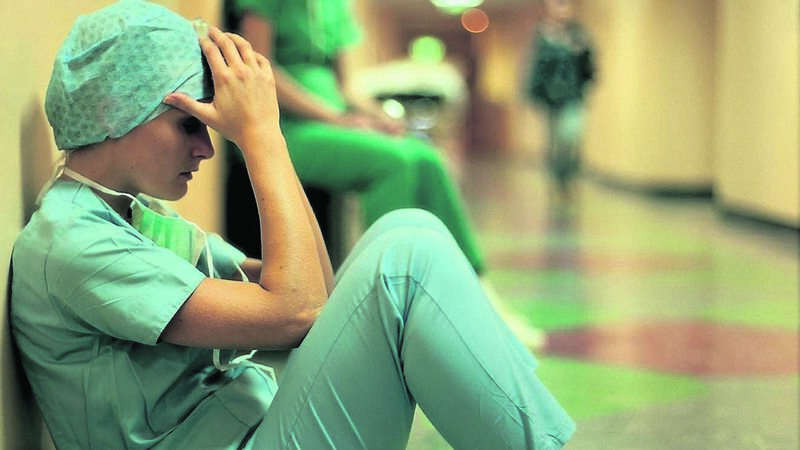

Doctors are ordinary people with ordinary limits. It is time for us to design systems of work that reflect these limits rather than ignore them. File picture

I looked at the clock: an hour to go until handover. Only the baby-checks left. I finished my notes for the last admission of the night — a two-year-old girl with a chest infection — and headed to the maternity ward. The ward manager greeted me cheerfully:

“Hiya! We’ve six babas for you to see this morning.”

My heart sank: six.

At weekends, one of the duties of the on-call paediatric doctor is to do that morning’s baby checks where, before going home, every newborn baby is examined head to toe. This is a key opportunity to identify a range of medical problems, from heart murmurs to clicky hips, some of which cannot safely wait until the baby meets their GP a few weeks later. I have always rather enjoyed them — the problem that morning was that it was the height of winter flu season, I was 23 hours into my shift and hadn’t slept.

I went to the loo and splashed some water on my face. Then I marched into the first room. All fine — I even managed not to wake the baby. The second baby was a little girl who had needed a forceps delivery. The third baby wore a baby-grow with a dinosaur on it saying ‘Roar!’, and roar he did. I wiped my forehead with my arm.

The fourth baby had impressive rock-star spikey black hair. I can’t remember the fifth or sixth babies. I jogged down to handover.

After the meeting ended an hour later, a colleague approached me.

“Anything you need me to follow up on?”

“One of the babies upstairs has a murmur. He looks fine, but maybe we should do his sats and blood pressure?”

“No problem”, she said.

“Which baby?”

I stared at the crumpled scrap of paper that had been serving as my filing system. All of a sudden, all of the babies melded into one.

“I have absolutely no idea. The one with the … woolly hat?”

“Don’t worry”, she said, kindly.

“I’ll sort it.”

I felt queasy as I walked home. I was not sure if it was exhaustion, hunger, or a creeping sense of guilt. I fell asleep on my bed with my jacket still on.

In Irish hospitals, doctors routinely work 24-hour shifts.

There have been improvements in some areas, but 24-hour-call remains common, particularly in specialities like paediatrics, obstetrics and surgery.

The medical profession has a strong cultural association with intense, demanding work. To some extent, it arises from the decidedly obvious fact that people can get sick at any time of the day or night, all year round. However, it seems doctors, in particular, are subject and ourselves contribute to a culture in which punishing hours are an almost inextricable part of our professional identity.

This culture is coming under increasing scrutiny. Our public health system is deeply understaffed, and bodies like the Irish Medical Organisation and the Irish Hospital Consultants' Association consistently draw attention to the corrosively harmful effects of this, for patient care and for doctors ourselves.

Hundreds of vacant doctor posts and impact of Covid-19 will lead to ‘crazy’ hospital waiting lists, warns IMO https://t.co/aF9EsCxBm6

— Irish Medical Organisation (@IMO_IRL) August 26, 2020

Further afield, laws such as the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) have been enacted in many jurisdictions to combat overwork, with mixed results. For doctors in some Northern European systems, an EWTD-compliant work week is the norm. In Britain, while 24-hour shifts are no longer common practice, NHS doctors are nonetheless understaffed and overworked. In Australia, while 24-hour shifts occur in some areas, work- life balance is distinctly better — as evidenced by the scores of Irish doctors moving there every year.

The time has come for a serious discussion about the ethical implications of doctors working 24-hour shifts.

The effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on a person’s ability to perform mentally and physically are established beyond doubt. Importantly, these effects are not subject to willpower: no matter how hard your work ethic, beyond 16 hours’ consecutive work, your reaction speed diminishes to a level equivalent to the legal alcohol limit for driving.

Moreover, it is unsafe for doctors ourselves — from the long-term adverse health effects of chronic sleep deprivation to the short-term dangers of driving home half-asleep.

Rethinking this system in favour of a maximum shift duration of, say, 13 hours would be a bold step. It would not solve all our problems, but it would certainly help. Of course, I can only speak for myself. In fact, many doctors are reluctant to change the status quo, holding valid concerns about doing so.

Some worry about losing continuity of care. If a patient requires an assessment during the day and again at night, it helps if the assessor is the same person. But this begs the question: how do nurses provide continuous care to patients round-the-clock?

They do this by way of handover: a short, focused exchange of information between the outgoing team and incoming night colleagues. (Whether or not the baby was wearing a woolly hat ideally should not feature.) As it is, doctors already do this — if more frequent deployment of this tool enables us to deliver safer care then it is the right thing to do.

Crucial targets in cancer care are being missed, often leading to reduced health outcomes for patients. @IrishCancerSoc calls on the Government to reverse years of underinvestment in our cancer services #CareCantWait @DonnellyStephen @MichealMartinTD @roinnslainte https://t.co/v0a3iIKURc

— IHCA (@IHCA_IE) September 3, 2020

Others argue discontinuing 24-hour shifts will have a detrimental effect on training. This is like an extreme version of the 10,000-hours argument — yet nobody has got to Carnegie Hall by playing the piano for 10,000 hours in a row. While I learn a lot at night in hospital, that has nothing to do with dispensing with sleep. Again, look at nurses — or pilots or pianists for that matter. It might take years to master a skill, but that doesn’t mean you should stay up all night to do so, endangering people in the process.

Perhaps the most persuasive counterargument is simply that, if you don’t have enough doctors, it does not matter how you arrange your rota: doctors will be exhausted, and patients will still be exposed to risk. If you do not have enough chairs, there won’t be a place for everyone to sit no matter how you arrange the furniture. However, there is a vicious cycle in action here, of endemically poor working conditions driving doctors out of the system, either from burn-out or simply a flight to Perth, making the problem worse. Removing 24-hour shifts will not itself resolve the issue of understaffing, but it provides an opportunity for us to interrupt this cycle.

In the end, the simplest argument for getting rid of 24-hour shifts is the most compelling: if your loved one were in hospital, you would not want their treatment to be delivered by a doctor who has been up all night.

When I enter hour 23 or 24, I knock things over when I reach for them.

I have had phone conversations with nurses, only to ring back a minute later for a reminder of what we just agreed upon. I grow impatient, and less able to put a child at ease.

(I like to think I am generally quite good at making people laugh, specifically those in the 1-to-5-year-old age bracket.)

First, we need to be honest about the investment needed. A commitment to ending 24-hour shifts must be accompanied by a broader effort at stabilising our medical workforce. In recent weeks, a HSE report forecasted the number of consultants providing care in acute hospitals will need to rise by 53% by 2028 just to keep pace with current demand. Today’s juniors are tomorrow’s consultants: we must invest in the system as a whole and provide a reason to stay. If, as taxpayers, we are unwilling to do this, doctors will continue to leave that system.

Second, we need to be practical, appreciating the different contexts across the system. In paediatrics, 24-hour call remains the norm, yet the forthcoming National Children’s Hospital by uniting the workforces of Temple Street, Crumlin, and Tallaght hospitals under one roof, provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity to modernise doctors’ work practices.

In contrast, surgery as a discipline is so understaffed that some junior doctors work for 36 hours straight, or whole weekends. Without increasing staffing, declaring an end to 24-hour shifts by the stroke of a pen will achieve little.

Third, we need to bring about a cultural change within medicine. Working while exhausted should be seen as less acceptable — the exception, rather than a norm hardwired into our rotas from the start. Just because something has always been the case does not mean it is right. Moreover, patients and families can play a role in such change. Take hand hygiene for example: pop-up banners now encourage patients to ask whether doctors have washed our hands. Just as I would expect to be called up for having filthy hands on a ward, patients should not be afraid to ask if their doctor has had enough sleep to perform safely.

Working through the Covid-19 pandemic has made me learn that healthcare staff are not superheroes.

Our hospitals are staffed by ordinary people, albeit working under extraordinary conditions. However, if we put a cape on someone, perhaps this leads us to assume they are superhuman.

Doctors are guilty of buying this illusion sometimes, leading to a fear of admitting that we can and do make mistakes when we are exhausted.

Whether it is resuscitating an elderly patient, performing surgery, or checking on a newborn baby, it is fundamentally inappropriate that doctors routinely work in a state of sleep deprivation.

Read More

Pilots do not do it, truck drivers do not do it, nurses do not do it.

Doctors are ordinary people with ordinary limits. It is time for us to design systems of work that reflect these limits rather than ignore them — for our own sake and for the patients under our care.