Jennifer Horgan: We should be looking closer to home for heroes like the late Don O'Leary

Don O'Leary of the Cork Life Centre was an everyday hero who dedicated his life to marginalised young people.

The song might say we don’t need another hero, but it turns out we do.

Sure, we can’t even gather a handful of qualified candidates for our presidential race. When someone as terrifyingly backward as Maria Steen calls for the whole thing to be scrapped, simply because she’s not in it, we know we’re in trouble.

As for our Government, we must now accept the Taoiseach’s office is incapable of conducting basic research. Norma Foley going on air to say “due diligence” had been conducted by her party certainly strikes a new low.

Ireland needs another hero. But maybe we’re looking in the wrong places for one. Maybe we need another type of hero altogether, not another presidential candidate, or a blundering politician, or a Hollywood star. Maybe we need someone completely ordinary.

I am terrified by how intelligent people speak about people in the public eye as if they’re close friends these days. I’m not saying we should get politically or culturally disengaged or anything. I’m just saying there’s a balance to be struck.

By celebrating everyday, ordinary heroes we might even create a knock-on effect, raising the bar for leaders — showing them how it’s done. We might benefit from less of the ‘trickle-down’ and more of the ‘evaporate-up’.

One difficulty is that everyday heroes are harder to see. There are a whole lot of people out there laying claim to being heroes, putting a lot of energy into ensuring they’ll be spoken about as such. They move like moths to the flame of the spotlight, revel in it.

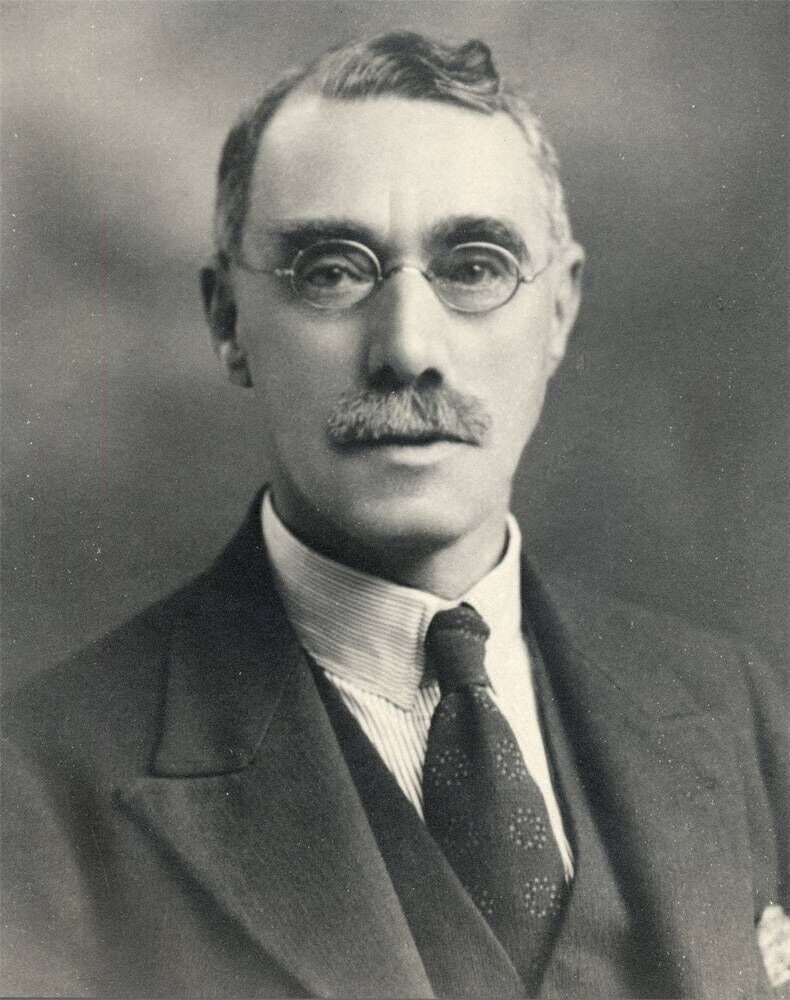

I came across a lovely book in Cork library this week by academic Mairéad Mooney. It’s about Cork’s longest-serving librarian, James Wilkinson. Few will have heard of him but he was a truly remarkable man, and his wife was a truly remarkable woman. She knitted 900 outfits for dolls which were distributed to poor children, bringing joy and magic when they were in short supply.

He worked as Cork’s librarian for 40 years, and prioritised children’s books in the free Carnegie library when nobody else was doing so. He even created a separate reading room for them when it first opened in 1905.

His passion had a direct impact on Cork’s young writers, Frank O’Connor referencing the “queer treasures” of Carnegie library in his memoirs.

A 1925 issue of claimed Rathmines as being the first children’s library in Ireland. Wilkinson had it amended to ensure Cork would always be recognised as the true innovator in this field.

This month hosts the Children’s Book Festival in our libraries. Check out the programme — city and rural branches are thronged with small bodies and big events. It all leads back to James Wilkinson.

His tenure wasn’t without its challenges either. When the beautiful redbrick Carnegie library was destroyed in the fire of Cork in 1920, he had to go about rebuilding his stock, working against the odds.

Wilkinson was an Englishman at a time when Englishness was far from ideal. The new state was adamant young Irish Catholic children should be protected from all English books and English influences, although Irish publishing was in its infancy.

This week is Banned Books Week, and as the number of banned books rises in Trump’s America, it’s nice to remember Mr Wilkinson, and how he fought against the same nonsense a century ago, stocking shelves for Cork’s children regardless of the books’ origins, believing in children’s boundless, borderless potential.

A similar everyday hero died only last week — educator Don O’Leary. His dedication to young people began with his own two children, then his beloved grandchildren, then spiralled outward to so many more, through his work as a youth worker, coach and at Cork’s Life Centre, a school for marginalised teenagers, over the last 18 years.

At his funeral Mass on Monday in Farranree, a sombre congregation heard from the Gospel of Matthew.

“Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.” That was Don O’Leary — a person who believed every life was sacred. And so, he would sit for hours with a young person let down by the system, believing in their potential, even if nobody else did, even if they didn’t believe in it themselves.

On the night after Don O’Leary’s service, I sat down to watch the film , starring Cork’s own Cillian Murphy and based on the short novel , by Max Porter.

Stanton Wood Manor, the residential school in which Steve works, is described at the outset as somewhere between a “waiting room for Borstal”, and “a last chance”. It is even referred to as an “expensive dumping ground for society’s waste product”.

The story of Steve chimes perfectly with the life of Don O’Leary. It is about the faith of teachers who refuse to see students, whatever their behaviour, as worthless.

Steve describes his young people as “extraordinarily complex”. He describes Shy’s “generous pain”. His deputy Amanda admits to “adoring” them. “You can’t just stop,” she says, or “Press a button and say no more.”

One particularly satisfying scene sees a politician (Roger Allam) visiting the boys. His tone and manner are grotesquely detached from the reality of the young people battling addiction, mental health issues, and family upheavals.

The man, confident he has wowed them with his little speech, asks for questions.

Shy, an incredibly compelling character played by Jay Lycurgo, takes him down with a few choice words. The politician, the national leader, the man who makes all the decisions, is revealed to be a sham. It is Steve who is the real leader, the genuine changemaker.

Steve reflects real people like James Wilkinson and Don O’Leary, everyday heroes who invest in single lives because they matter.

The minister represents the political leaders who so often let us down.

I have great respect for Cillian Murphy for taking on this role in a film he describes as a “love letter” to teachers.

By inserting all his fame into an ordinary character like Steve, he highlights the extraordinariness of everyday heroes. He is utterly convincing in the role too, caring for his boys in his crumpled shirt, his face unshaven, his nerves shaken.

So yes, we might be better off looking closer to home for our heroes. People who might not shout or promote their own great deeds, but who are quietly spectacular, working away in their own little corner, building something in the quiet and the dark.

The book of condolence for Don O’Leary, located in Cork City Hall, is available to the public to sign between 10am and 4pm, Monday to Friday, for the next two weeks. If you have the time, and I understand few of us do, it’s worth signing.