Jennifer Horgan: I really admire Joan Didion’s work — that's why I won’t buy her new book

Writer Joan Didion receives an Honorary Doctor of Letters in Harvard Yard in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2009.

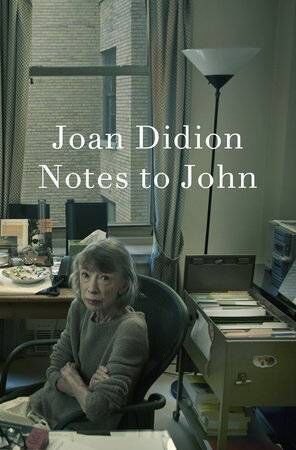

In the foreword of the last book she published months before her death, , is a quotation from its author, Joan Didion. “The peculiarity of being a writer is that the entire enterprise involves the mortal humiliation of seeing one’s own words in print.” Didion must have assumed this was to be the last time she’d experience such a thing, and it was. But it wasn’t the last time the world would see her words in print for the first time.

No, that will happen in a few weeks, when a new Didion book will hit our shelves, a book she never chose to publish.

It’s not usual for me to pick out the books I won’t be buying. Not usual but then, nothing about this book is usual.

by Joan Didion is a book I will never read because it’s a book Joan Didion never handed over to her most trusted literary aides.

It really isn’t easy for me to not read it. Didion is a writer with whom I’ve always been a tad obsessed. It’s just her vibe that bewitches me. Her coolness in both physical presence and literary style.

I have devoured her personal writing — both and . This work is far more accessible for a non-American reader, being universal in how it stares death down, embracing the logical madness living with grief entails.

It’s captivating. There is her whole relationship with her deceased husband’s shoes and how she wants to keep them for when he returns. There are her earliest memories of her adopted baby, Quintana, and how overwhelmed she feels seeing her for the first time — this impossibly cool woman, who you could never imagine being rattled, tells all.

Yet despite how personal the subject matter, there is always an awareness of the reader reading. Didion meant for these ostensibly revelatory books to be read by strangers. There is a great generosity to them therefore. She hopes to help others in their grief.

As noted in magazine “The raw emotional weight of both and provides an unflinching look inside Didion’s otherwise steely, sophisticated exterior. In letting her guard down, she allows readers into her grieving process — and provided a roadmap for others navigating their own pain.”

Didion wrote for a reader, always. I remember her recounting in an interview a moment in San Francisco, at the height of the drug-fuelled hippy movement, when she came across a baby on acid. She acknowledged that it was terribly sad, but she also referred to it as being ‘gold.’ She was a professional writer through and through. She wrote for strangers, and so compelling an image, a stoned baby, was indeed gold.

I’ll enjoy any work that is willing to be upfront about what we most avoid, or what is most shocking — but only if the writer knows I’m there, reading.

This is the reason why I will not buy . Because Joan Didion never had it published. It’s reportedly a diary, filled with explorations of her struggles with anxiety, guilt, and depression, her relationship with her daughter, and her musings on her legacy.

Publisher Jordan Pavlin names the elephant in the room when she says “Didion’s art has always derived part of its electricity from what she reveals and what she withholds.” Adding: “ is unique in its lack of elision.”

It is being described as the last part of ‘a triptych,’ according to another Didion fan, Edel Coffey, who spoke about it on RTÉ Radio. The book is seen as a follow-on from those two favourites of mine, and . But can it form a triptych when the third instalment is being offered by publishers and not by the writer herself?

Certainly, it will be similarly personal — but too personal. It’s a book made up of notes Didion addressed to her husband, her first reader and, in this case, perhaps her intended last reader too. We can’t know, but what we do know is that the notes were written in 1999, following therapy sessions. She died in 2021. She had 22 years to decide to release them and she didn’t. Her final book was not this book.

In her interview with Brendan O’Connor, Edel Coffey also makes the astute point that although Didion dealt with excruciatingly personal stories, like the death of her child and husband, she always kept a certain distance. She was forever poised and crafted. This is the Didion I know, and this is the Didion she chose to present to the world.

She made very clear-cut considered goodbyes to the world long before her death. She published a final collection of essays. She very obviously stopped attended events — this from a woman who was known for her parties. In 2012, President Barack Obama presented Didion with the National Medal of Arts and the National Humanities, marking one of the last times she was seen at a public event. She last appeared in a 2017 Netflix documentary, , directed by her nephew, Griffin Dunne. She crafted her goodbye, and now her publishers appear to be providing their own epilogue.

Yes, I said it. Misogyny. There is a long and colourful history of the letters and diaries of women being dissected long after their death, from Daphne du Maurier to Emily Dickinson and it makes me deeply uncomfortable — considering what little freedom women historically had in their lives. It feels wrong to invade their most personal spaces, shared with only their most intimate correspondents. These were possibly their only places of retreat, their sanctuaries. If, giving just one example, Daphne Du Maurier didn’t want the world to know she was bisexual, then she didn’t want the world to know she was bisexual. Somebody did very wrong by making that public.

Closer to home, it also reminds me of the invasive use of women’s histories in Irish courts. As it stands in Ireland, a victim’s counselling notes can be used as evidence if they are deemed to be relevant to a rape case. Susan Lynch, who was raped by her former partner, said in her victim impact statement that she did not receive any counselling because she feared they would be read out in court. In the most extreme and violent cases, a woman’s word can be turned against her. Rachel Morrogh, the chief executive of the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre rightly says, “no victim should ever have to choose between counselling and court.”

Women even now, in too many circumstances, have too little control over their lives and their wellbeing. They should at least have control over their most intimate exchanges.

Women should have control over their death, over how they wish to end their relationship with the world, and, in Didion’s case, with readers. Most especially when the material is so intimate.

Philip Larkin famously said that what will survive of us is love. When it comes to Joan Didion we don’t seem capable of offering anything even close to love. Poor Joan.