Michael Moynihan: Caro exhibition shows meticulous research behind a masterpiece

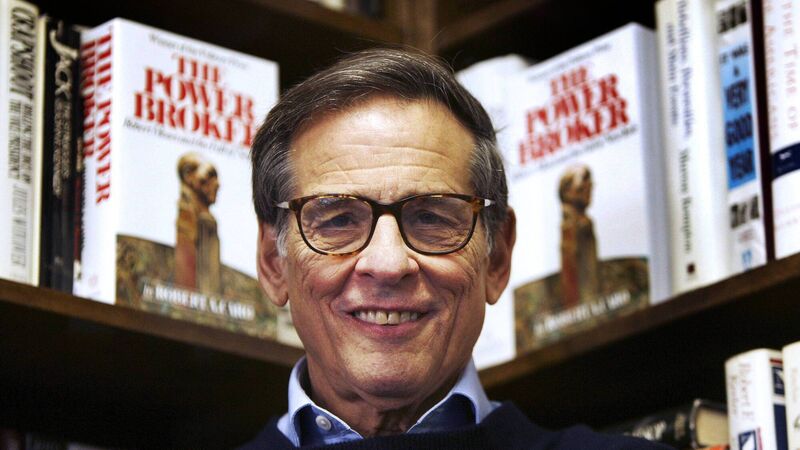

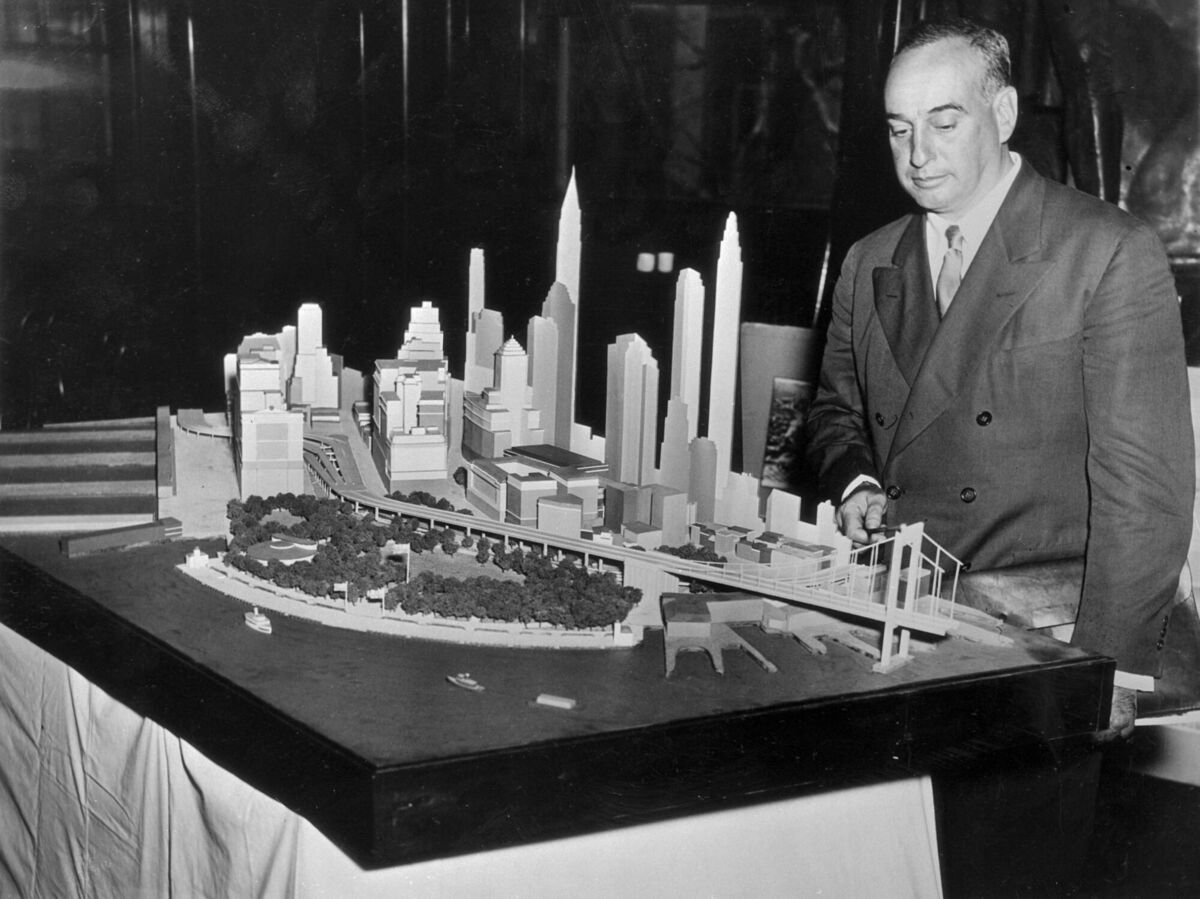

Robert Caro, author of 'The Power Broker', a biography on Robert Moses, poses in his office in New York in 2007. Picture: Getty Images

Lynx-eyed readers may have noticed from the paper this last week that I was in the US recently.

While there someone said to me there was a Robert Caro exhibition, based on the fiftieth anniversary of , up at the New York Historical Society HQ near Central Park. He barely had the words out of his mouth when I trampled him underfoot sprinting uptown.

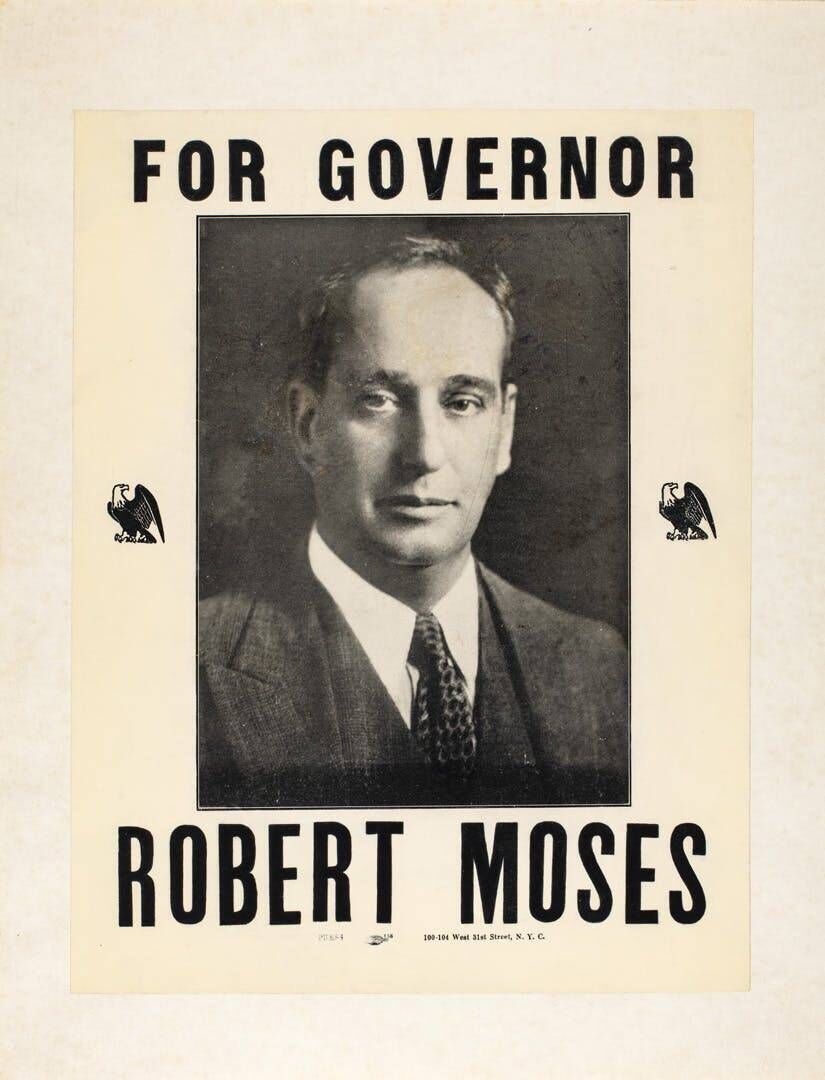

Caro spent years writing . Its subtitle, , hints at the topic — the career of Robert Moses, an unelected official who dominated municipal building in New York from the 1930s to the late sixties. Moses built bridges and roads, beach resorts and public parks, spending billions to transform New York.

He also obliterated neighbourhoods and communities and bequeathed a tangled infrastructure which often works against its own citizens even now.

Caro explains how Moses acquired and exerted power, and shows what that power does to a person, in one of the greatest works of non-fiction of all time.

Since then Caro has spent decades writing a magnificent multivolume biography of Lyndon Johnson — one chapter in volume I of that series, , is a masterpiece in and of itself.

But exerts a strong pull even now, a full half-century after it first appeared. This is partly due to the legend of its composition. In the seven years Caro spent writing the book his advance ran out, and he returned home one evening to find his wife Ina had sold their house to fund his research.

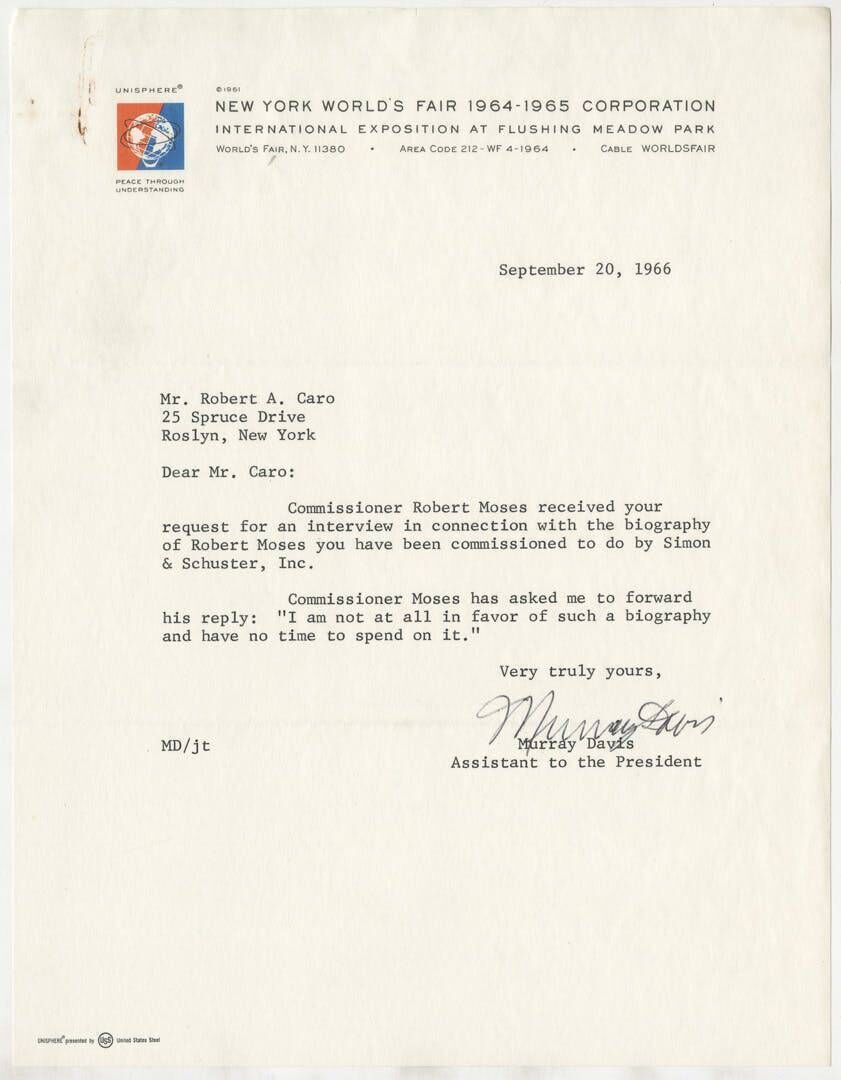

The subject of the book, Robert Moses, tried to obstruct his work; one of the editors he was dealing with dismissed the book’s prospects. (The editor’s scepticism was understandable in one sense. When published the book ran to almost 1,300 pages and weighed four pounds.)

Why did it take so long? Part of that was down to Caro’s meticulous research. As a young journalist he was advised to turn every page, something he took to heart with .

One of the exhibits at the New York Historical Society shows Caro’s typed notes from interviews he conducted with Sidney Shapiro, one of Robert Moses’s top aides.

The information panel accompanying the notes tells readers that Caro struck up a rapport with Shapiro over the course of 100 hours of interviews.

His work found a fitting partner in the great editor Robert Gottlieb, who wrestled a manuscript of one million words into publishable shape (to do so he cut 350,000 words, four or five normal books’ worth of text).

Until Gottlieb passed away last year, the two men had a very fruitful working relationship, though hardly as fruitful as that of Caro and his chief researcher — his wife Ina, herself a successful author.

Caro once told Ina that to research Lyndon Johnson’s early life they would have to understand his background and move to the desolate hill country of Texas — which they did, for three years.

“Why can’t you write a biography of Napoleon?” she asked.

Caro enjoyed a revival of interest during the pandemic, when Zoom interviews on TV became an accepted form of interaction.

It soon became clear that , with its unmistakable bulk, had become one of the books many American contributors positioned prominently on their bookshelves when speaking to camera. Its presence was an immediate signifier of seriousness, one so obvious that drew attention to the phenomenon (headline: “Lights. Camera. Makeup. And a Carefully Placed 1,246-Page Book.”) All of this does the book a disservice. Its granular examination of Robert Moses’s slow ascent to power and his subsequent grip on the city of New York is not just a masterpiece of investigation but a moving portrait of how a city changes.

One of the most powerful sections of the book is simply entitled 'One Mile'. Caro examines how one mile of the Cross-Bronx Expressway was built, and how that one mile destroyed a community, that of East Tremont.

“One Mile” traces the story from start to finish — how letters arrived informing residents they would have to leave in the early fifties, their efforts to protest, how politicians rowed in behind Moses, and the eventual forced departure of thousands of families from the area.

Caro’s stark account of the area’s decline was published before it became a byword for urban decay in subsequent decades, not to mention the high rates of respiratory illnesses eventually caused by the expressway. Or the terrible traffic congestion caused by the very measure which it was built to relieve ... traffic congestion.

At the exhibition mentioned above visitors can read Caro’s handwritten notes about East Tremont, and typed drafts with additions scribbled along the margins and excisions blacked out. They can also see his Pulitzer Prize for the book and the accompanying citation.

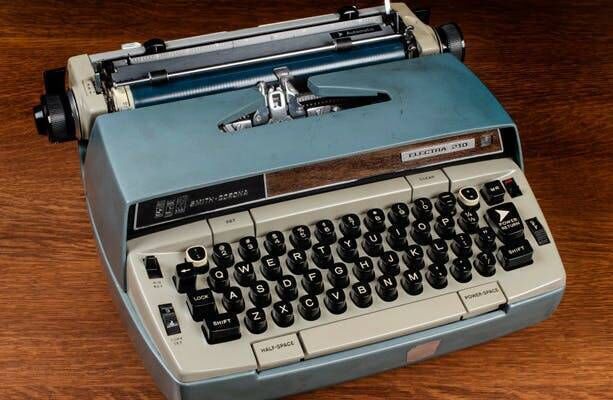

They can even see his typewriter: Caro still uses a Smith Corona Electra 210 typewriter and one of the ten he uses is on display at the exhibition.

It’s a matter of some concern to his fans that a lack of working typewriters may impede his work on the last Lyndon Johnson volume. He told the in 2021 that he sometimes has people contact him to offer their old typewriters, though he added that sometimes they say, “‘Oh, I have one in the garage. I’m such an admirer of yours. I’ll sell it to you for four thousand dollars.’ So I accept all the free ones.”

Readers can probably guess the attraction of the Robert Caro exhibition for someone who writes a city column, or indeed the attraction of his work, full stop.

They can decide for themselves whether some of the follies he uncovered in urban planning and construction over fifty years ago still exist. In truth, not too far from this writer’s desk one can see where local authorities have hung dual carriageways through communities, for instance. Or simply added roads to an already overburdened interchange in an effort to relieve traffic congestion.

There’s also the Caro work ethic to admire.

At one point Robert Gottlieb was reading a scene in set in the late 1920s: Robert Moses’s parents, at a holiday camp in upstate New York, received a telegram telling them their son had been fined $22,000. In the manuscript Moses’s mother was quoted as saying: “Oh, he never earned a dollar in his life, and now we’ll have to pay this.” Gottlieb rang Caro and asked the obvious question: how could he possibly have quoted Mrs Moses verbatim when clearly he hadn’t been present when the incident had happened, over 40 years previously?

Simple, said Caro. He had tracked down the people who worked at the camp and contacted them all until he found the one who’d delivered the telegram and asked him what had happened.

That’s how it’s done.

For more information visit here