Hike the mountain which straddles Limerick and Tipp border — with views from Kerry to Wicklow

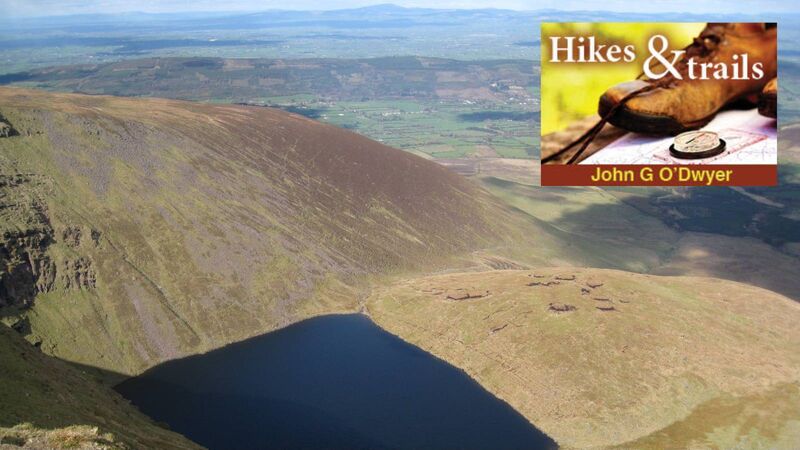

John G O'Dwyer: "The circuit of Glencushnabinna in the Galtee Mountains is one of Ireland’s finest upland outings." Pictured — Lough Curra

If you hike the circuit of Glencushnabinna in the Galtee Mountains, you will soon become aware of completing one of Ireland’s finest upland outings, but you may be less cognisant of the abundant history beneath your boots.

Most likely you will follow a well-worn path from Clydagh Bridge Carpark through Glencush Wood before gaining open mountain and tagging a stony trail known as the Ice Road to reach Lough Curra — a corrie lake created by glaciation. Used to extract ice from the lake at a time when Irish winters were much colder, it was then placed in the ice houses of the large estates. These buildings created a microclimate which, before the invention of refrigerators, was used for cooling and preserving food.

In the cliffside south of Lough Curra you can visit a small, wet fissure in the mountainside, which is known locally as Dan Breen’s Cave. Breen was a renowned freedom fighter from the South Tipperary area, who, as a member of the Third Tipperary Brigade, was instrumental in starting the War of Independence at Soloheadbeg in 1919. There is, however, no hard evidence linking him to this uncomfortable hideout in the mountains, although he was finally captured while hiding in a nearby dugout during the Irish Civil War.

Beyond Lough Curra, a steep ascent known locally as The Ramp will convey you to the Galtee Ridge and an immediate encounter with a stonewall. Built without mortar and sometimes described as a Famine relief project, it is actually from a later time and was constructed during a severe agricultural depression to separate the huge Massey-Dawson and Galtee Castle estates. Caused by bad harvests and a partial return of potato blight at the end of the 1870s, the aim of the wall was to provide work for unemployed local men affected by the depression. Measuring 3.5 kilometres, it runs across the mountaintops west of the Galtymore and is now a valuable navigational handrail for those completing the full Galty Ridge walk.

Onwards and upwards now to reach the 918-metre summit of Ireland’s highest inland mountain, which is shared by counties Limerick and Tipperary. On a clear day, the views are a superb vista across Ireland from Kerry to Wicklow but your eyes will sooner-or-later be drawn to a pristine white cross adorning the summit.

With the influence of the Catholic Church then at its zenith, there was an abundance of cross-building on the Irish mountains to celebrate the Holy Year of 1950 and the Marian Year of 1954. At this time a wooden cross was erected on Galtymore, but in 1962, it was decided to place a large limestone cross on the mountaintop.

Because of its great weight, the cross was carried most of the way to the summit onboard the Katie Daly — an army Bren Gun carrier. It was then officially blessed in June 1962 before a large crowd who had made the laborious climb for the occasion.

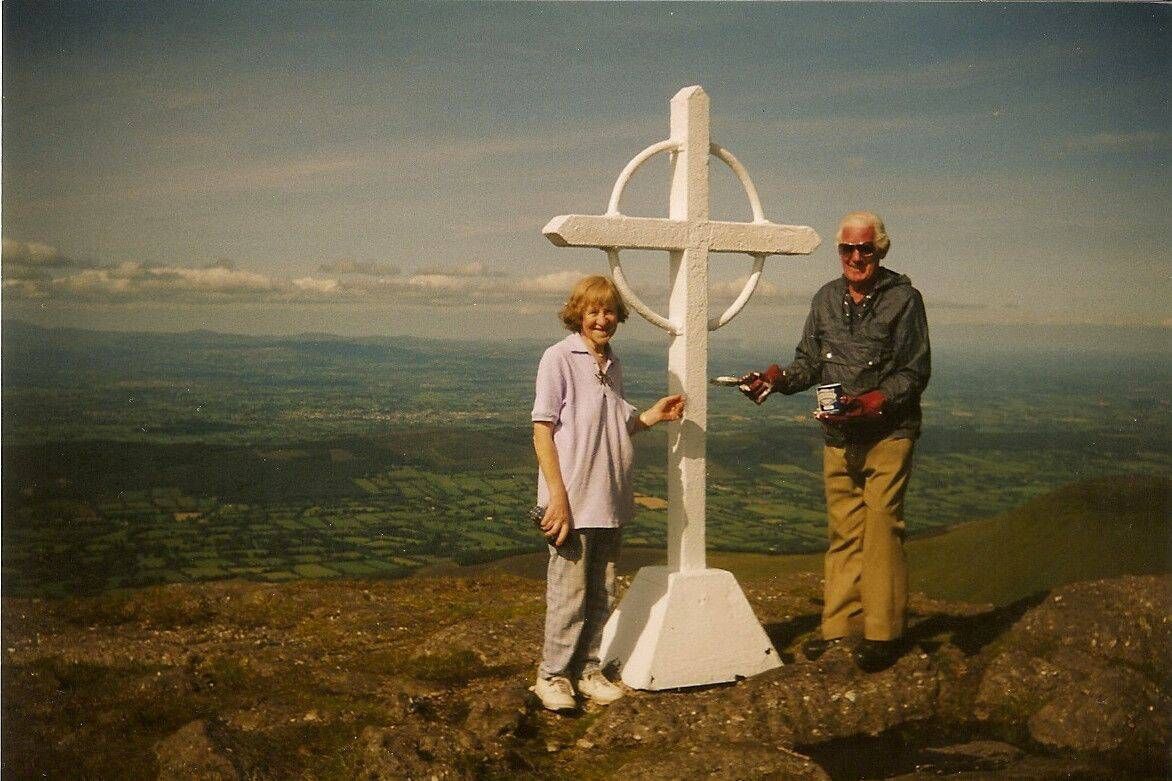

After this cross fell victim to a winter gale, it was replaced by the steel Celtic Cross that now adorns the summit. Designed by Ted Kavanagh in his home in Tipperary town, its components were carried to the mountaintop with help from the Tipperary Adventure Sports Club. Having been assembled, the cross was then blessed by local priest, Fr Tom Breen, in June 1975.

Ever since, the cross has remained in pristine condition as each year Ted Kavanagh and his wife Joan climbed Galtymore to paint it, a duty that has now been taken over by renowned local hillwalker, Jimmy Barry.

Next, a descent of Galtymore is followed by a traverse over Galtybeg Mountain, which leads to the route of an old trail known locally as the Geisha Steps or Gate Steps. This runs high above the perfect teardrop shape of Bohreen/Borheen Lough.

Unlike nearby mountain ranges, such as the Comeraghs and Knockmealdowns, there are no roads crossing the Galtees. Local people could, however, walk from the south side of the range to the north (or vice versa) by following the path presently known as the Black Road, which was initially created to draw turf from the mountainside. Beyond, the Geisha Steps could be used for the descent into Aherlow.

Local stories still recount tales of hardy mountain men crossing the mountains by this path to enjoy a pint in Skeheenarinky.

Now follow the Geisha Steps into the valley. If you wish to complete the full circuit of Glencushnabinna, you must undertake a thigh-burning ascent over Cush, which is a rewarding mountain in its own right, and then follow a path down to Clydagh Bridge. For an easier option, you can walk northwest to gain a stile leading into woodland and then take a forest path back to Clydagh.

- The latest edition of John G O'Dwyer's book is out now from publishers, Currach Books