A ray (or skate) of hope: Tracking the world’s largest skates in the waters off County Cork

Courtmacsherry has an abundance of flapper skates so CETUS Skate Research Project, led by University College Cork and partnered with Inland Fisheries Ireland, aims by 2025 to collate existing data on these animals and generate new data using animal tracking technology or 'biologging'

Irish waters contain 71 species of elasmobranchs — a group that includes sharks, skates, and rays. This list includes small sharks and rays, such as dogfish and thornback rays that are considered abundant and regularly caught by anglers, to rarer large-bodied species, such as the porbeagle shark and flapper skate, measuring over two metres in total length.

There are two key uniting features of all these species:

Firstly, their use of Irish waters.

Secondly, we do not know much about them — why are they here, and where do they eat, sleep, and breed?

This knowledge is central to effectively protecting threatened species or managing abundant species as a resource (eg. as food or for recreational fishing). The generic reporting of catches and confusion over animal identity has also led to uncertainty in the population status and health with information lacking on species-specific catches, species distributions, population size and structuring — a problem that remained until 2009 and mandatory EU reporting of catches to species-specific levels.

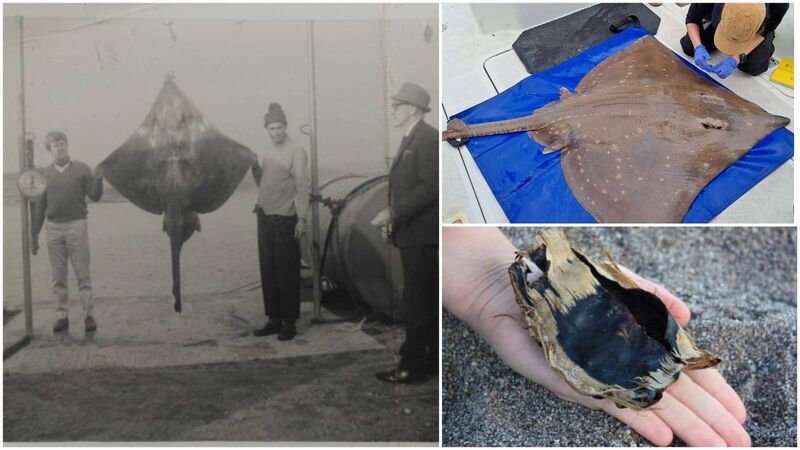

Successful start to the week with the first skate tagged in Courtmacsherry. Over the next 2 yrs we will be tracking its movements to identify residency within one of the last known refuges for this species in Ireland 🌊 pic.twitter.com/pRi4vZLBDb

— Danielle Orrell (@DaniOrrell) June 14, 2023

Biodiversity describes the rich diversity of life on Earth, from plants, animals, and fungi to other living things. According to recent figures, global wildlife populations have plunged by 59% on average from 1970 to 2018. Extinction is happening not only in tropical rainforests or on the Great Barrier Reef but also on our doorstep. In Ireland, only 2% of native broadleaf woodland remains, and 25% of regularly occurring bird species are in serious decline. A recent Citizens' Assembly on Biodiversity loss appealed for an immediate call to action. With at least one-third of Ireland’s protected species in decline, a trend happening on both land and in water, urgent action is needed. Central to the effective conservation and management of vulnerable species is a need to know more about where they are found and what resources they need to survive and thrive.

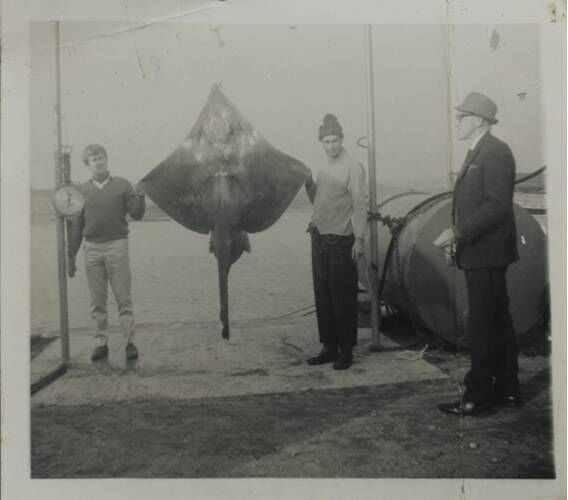

The flapper skate is one such species that has benefited from changes to European legislation. Since 2009, it has been prohibited to catch and land this species. Once prevalent across European waters, flapper skate populations sharply declined due to unsustainable harvesting and lethal angling practices in the 1970s and 1980s. Until recently, the flapper skate, the largest saltwater skate in the world, was known and described as the ‘common skate’. Using genetic analysis, researchers identified that the common skate included two separate species, the flapper and the blue skate.

You may ask, why does this matter? While it was known the ‘common skate’ was in decline, the fact that this describes two entirely different species means historical catch records and reporting of this animal is thrown into question. It also raises the question, how do these two very similar-looking animals differ beyond their DNA? This dilemma leads us to today and a global race to understand an animal on the brink of extinction.

Despite its conservation status, research into flapper skates is still ongoing, and significant gaps in current knowledge still need to be addressed. The flapper skate has several features that leave it vulnerable to population decline. Firstly, they are large-bodied and often reach more than two metres in total length — this means that while it has been prohibited to land them since 2009, they may be caught accidentally in trawl and tangle nets. Secondly, they are long-lived and slow-growing. While the maximum recovered age is around 43, it is thought it could live up to a century. They are slow to mature, with males reaching maturity at 7-16 years old and females between 9-26 years old. According to current knowledge, this means females may not reproduce until they are middle-aged. Females produce only 40 eggs a year, with only one or two laid at a time; once laid, these eggs lay unprotected on the seabed for 18 months before the skate hatches, making them vulnerable to seabed disturbance. It is important to note that there is only one documented egg lay site for this species, found off the west coast of Scotland. This begs the question, are there any egg lay sites in Irish waters?

The CETUS Skate Research Project, led by University College Cork and partnered with Inland Fisheries Ireland, aims by 2025 to collate existing data on these animals and generate new data using animal tracking technology or 'biologging'. Acoustic tracking enables researchers to study the movements of aquatic animals by either externally attaching or internally implanting a tag. An acoustic tag can be as small as a grain of rice to the size of an AA battery.

By deploying underwater listening devices called 'acoustic receivers' at points of interest in the environment, each tagged individual can be tracked for up to 10 years as they move within a specific area. This technology has fuelled our understanding of animal movements over the last half a decade and has been used to identify spatial management tools to ensure effective animal conservation and fisheries management.

This brings us to the village of Courtmacsherry, a quiet town with a vibrant community on Cork’s coastline with a rich fishing history and an abundance of flapper skates.

1) identify the seasonal residency within Courtmacsherry Bay (how long are the skate here?)

2) assess potential lay sites (do they lay eggs here?)

and

3) identify new tools that can increase the knowledge acquired from these interactions.

We hope to answer these critical questions by using tracking technology, including ultrasound (to investigate reproductive health) and genetics (to confirm species identity). This work would not be possible without the support of the Courtmacsherry community, who facilitated this work, and Courtmacsherry Angling and West Cork Charters, for their continued support.

Working with the local fishing community and other water users, we hope to demystify this charismatic yet cryptic species. A species that remains a ray (or skate) of hope in Ireland’s push to preserve its aquatic biodiversity.

- Dr Danielle Orrell is an aquatic ecologist