Richard Collins: Stunning work once dismissed as that of a self-taught amateur with ideas above his station

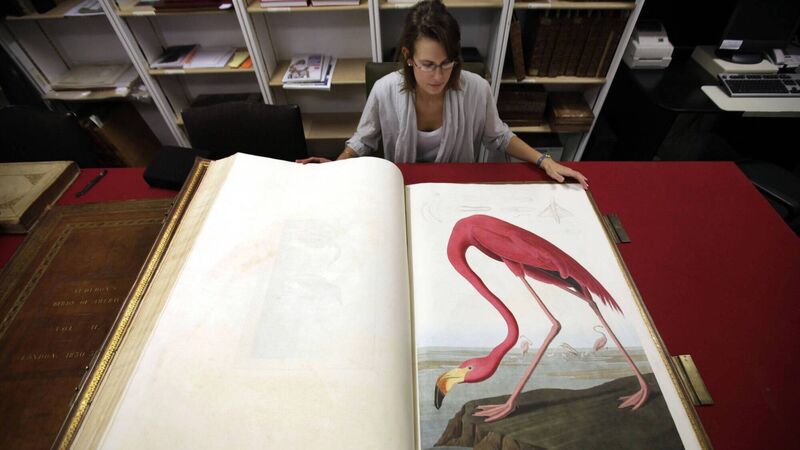

Sotheby's auction house worker Mary Engleheart, goes through a rare copy of a book of illustrations by John James Audubon's 'Birds of America in central London. Picture: AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis

— Emily Dickinson

Audubon was not the first person to depict all of America’s birds. That distinction goes to a Scotsman, Alexander Wilson from Paisley, the ‘Father of American Ornithology’. Audubon did have a Scottish connection, however; it was in Edinburgh that his talent was first recognised. An exhibition of prints from his Birds of America is being held there to commemorate the connection.

John James Audubon was born in 1785 in Haiti to a French naval officer and a chambermaid who died soon after the child’s birth. When six years old, the boy was taken to Nantes where the officer’s wife raised him as one of her own.

She encouraged his interest in nature, even allowing him ‘mitch’ from school to pursue, and draw pictures of, birds. In 1803, aged 18, he fled to America to escape conscription into Napoleon’s army.

Young Audubon did not prosper in America. His business ventures there all failed. To make ends meet, he tried selling drawings and prints. This led on to an ambitious project; he resolved to depict every American bird species.

Wilson had already done this with his multi-volume American Ornithology, but Audubon hoped to upstage him. Extensive travel, often with severe hardship, followed. He claimed never to have used mounted specimens as models, but always worked directly from life.

The prints he produced broke with the conventions of his time. Each species was depicted life-sized and in typical habitat. Movement and drama were included where possible.

His golden eagle, for example, is shown with a snowshoe hare in its talons, flying over mountainous terrain under an atmospheric sky. The osprey carries a beautifully illustrated fish it has just lifted from the water.

The work was dismissed as that of a self-taught amateur with ideas above his station. Audubon also drew attention to errors in Wilson’s opus. This hardly endeared him to the great man and didn’t help him secure the services of a publisher in Philadelphia.

The breakthrough came in 1826 when he visited Edinburgh, the centre of the Scottish Enlightenment. A consummate self-publicist, Audubon reinvented himself there.

Wearing frontiersman attire with his long black hair held in place by bear fat, he cut a dashing romantic figure, impressing the great and the good, including Walter Scott.

The publisher W H Lizzars spotted his talent and began reproducing the prints. When a strike in Edinburgh intervened, the work was transferred to London.

Few original copies of Birds of America, Audubon’s magnum opus, have survived. The 435 plates appeared between 1827 and 1838. More than 40 pages of them, beautifully mounted and lit, are displayed in the National Museum of Scotland’s exhibition.

Having acquired an A4-sized facsimile copy of the work many years ago, I was familiar with most of the pictures but this didn’t prepare me for seeing the breath-taking metre-high originals with their stunning colours, last week. They are among the finest wildlife depictions ever created.

Audubon died in 1851. The Audubon Society, the first American organisation dedicated to protecting birds, was founded in Boston in 1886.