Mission aims to find if there is life on Mars

Methane could provide one of the biggest clues to whether life exists on Mars.

A primary goal of ExoMars, the two-stage joint European/Russian mission to search for life on the Red Planet, will be to look for the gas and establish where it is likely to have come from.

On Earth, the chief source of methane is bacteria. Billions of flatulent microbes, including many that thrive in the guts of animals such as cattle and termites, belch out the gas.

But methane can also be released by volcanic activity and geological chemistry.

Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), which forms part of the first ExoMars mission due to be launched on Monday, has super-sensitive instruments for detecting minute traces of methane and other atmospheric gases.

It will look for methane "hotspots" over the Martian surface, and, crucially, test whether the gas is likely to be the product of biology or geology.

If methane is found in the presence of complex hydrocarbons such as ethane and propane, that will be a strong clue pointing to life. On the other hand, if it is accompanied by sulphur dioxide that would suggest a non-biological origin.

On Earth, life also prefers a particular "lighter" atomic strain, or isotope, of carbon, C12. If the Martian methane contains proportionally high levels of C12 that will be another indication that it has come from living things.

However, the very existence of methane on Mars is controversial.

The gas is easily destroyed by sunlight and in order to persist in a planet's atmosphere must continually be regenerated. That would imply an active process of some kind, whether living or not.

Scientists analysing data from Earth-based telescopes in Hawaii and Chile, and the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter, independently claimed to have discovered methane in the planet's atmosphere in 2003 and 2004.

But the amounts were tiny - around 40 millionths of methane's concentration in Earth's atmosphere, and detecting it took a lot of data crunching.

The Nasa rover Curiosity apparently got a whiff of methane on the Martian surface, but it was very brief.

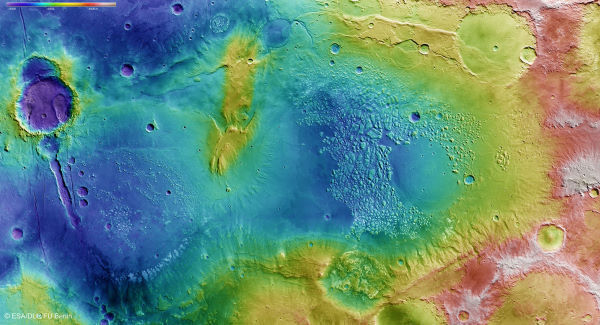

A big mystery about the reported Martian methane is that it seems to be concentrated in certain locations, and its distribution varies with the seasons. Again, this could have either a biological or geological explanation.

Dr Peter Grindrod, lecturer in planetary science at Birkbeck, University of London, said: "There is some uncertainty about even the detection of methane, which was initially done using Earth-bound telescopes.

"Curiosity found no methane at first and then got a spike that was above the level of background noise. It took about five measurements, then it dropped back down to zero again.

"The first job will be to confirm the presence of methane, and show how much there is. Over time when there's enough data we'll be able to address the question of the source of methane."

He said if TGO found evidence of biological methane it would generate "phenomenal" interest in the second stage of ExoMars, which will launch a British-built rover to Mars in 2018. The rover will drill two metres (6.5ft) under the planet's surface and analyse samples looking for biochemical "fingerprints" of life.

Dr Manish Patel, from the Open University, who leads the team in charge of TGO's ultraviolet spectrometer instrument, said: "Methane is a biologically relevant gas but its presence on Mars is controversial. This mission (ExoMars 2016) was born out of that controversy to solve this question.

"We will map the methane globally and take vertical profile measurements, not only seeing where it is but whether it is close to the surface, evenly distributed or at the top of the atmosphere. We can start to follow it around. If we see a glob of methane we can backtrack and see where it came from."

Geological methane may be generated by volcanic activity or water reacting with the mineral olivine, or released from clathrates - frozen ice-like deposits that trap the gas in a chemical "cage".

Not long ago Mars was regarded as a geologically "dead" planet. Today many experts believe there is still volcanic activity bubbling under its surface.

Olympus Mons, the solar system's biggest volcano - which towers to a height of 16 miles, making it three times higher than Mount Everest - is thought to have had its last major eruption as recently as 25 million years ago. This is far too long ago to account for any methane in the Martian atmosphere, but some scientists think the volcano, and others near it, are still geologically active.

Dr Patel stressed that searching for life on Mars was a complicated business and it would be wrong to jump to dramatic conclusions too soon.

In particular, care had to be taken about the C12 measurements, he said. Whether or not a certain fraction of "light" carbon meant the methane came from bacteria depended on your starting point.

An increased proportion of light carbon above the non-biological baseline level suggested life. But the baseline level on Earth and Mars may not be the same.

"There's a debate about this at the moment," said Dr Patel. "Looking at the isotopic fractions works on Earth because we know the carbon reservoir on Earth. We're still trying to figure out what the baseline is on Mars."