Jennifer Horgan: RTÉ’s Housewife of the Year shows us what we still refuse to see

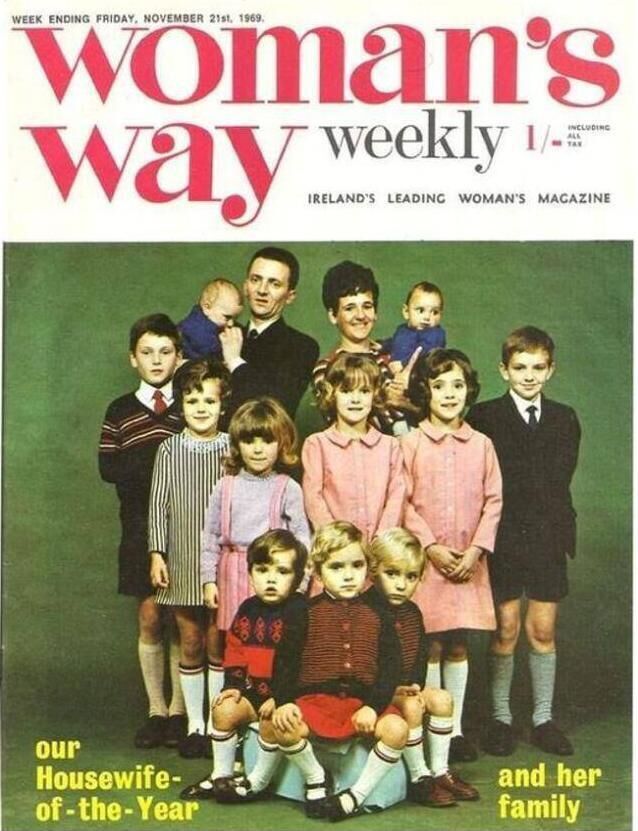

Among the women taking part in the 'Housewife of the Year' documentary is 1969 winner Ann McStay from Ballyfermot. The documentary is now streaming on the RTÉ Player. See link at foot of this article.

A friend messaged that she was “sick” watching Housewife of the Year, the documentary, on RTÉ. “I’m turning it off.” Horned emoji.

“Housewife of the Year in 2025, I can’t believe it,” said another, unaware that it’s a documentary, now running on the RTÉ Player, about the contest.

I was interested that anybody could imagine such a competition happening now.

Then I thought, why not? What would be so terrible about it? So many women I know are deserving of an award for the lives they live — juggling children, gardens, dinners, washing, parents — all while managing their own career, some without a partner.

Sitting down to watch, the thought stuck: Was the competition, which ran annually for almost 30 years up to 1995, so desperate?

In a certain light, it was a lovely event for women in an otherwise bleak time. The competition wasn’t the problem — broader society was; the strict and omnipresent power of the Church.

One participant describes her experience as “a break” from hordes of children. Another mother of a dozen recalls being embarrassed, carrying a pot of stew home from a food centre on the bus, the father having “receded” into the pub. “You could smell it — I used to be mortified.”

Mortified or not, she did it to feed her kids.

The documentary doesn’t just highlight the failing of the Church, it highlights the shortcomings of men, another husband and father leaving without a word — no letter, no pound note on the table.

Why shouldn’t these women have been celebrated?

The competition at least paid attention to the truth and the hardship of their lives. They were holding the sky up — making clothes, rugs, and cushions, making dinners, doing the homework, keeping everything clean and orderly, even in extreme poverty.

These women were being exploited — by the Church, their husbands, the marriage bar, and by broader society. They deserved recognition for surviving such exploitation so gracefully, managing to care for everyone when they were offered so little care themselves.

They deserved a day out, a new dress, and a new cooker.

Yes, Gay Byrne comes across as cloying but you can see he admires their achievements. And sure, we scoff at the promise of a new cooker but it’s easy to scoff when you can afford one and don’t have 10 hungry children tugging at your skirt.

It was only the end of the competition that drew attention to its purist attitudes towards women. One of the final winners was too flamboyant, too well-educated — a woman who had travelled. No, not acceptable. And so, a silence fell over the work of homemakers. We couldn’t box women into being housewives quite so easily, and so we began to say nothing at all.

You could argue that The Rose of Tralee is the replacement but it’s not, is it? There are no questions about homemaking and cooking there, no praise for mending clothes so as not to throw them away. We view it as backward to ask. Presenters steer towards education, careers, and global politics. Why?

Housework is a hugely important part of society, as is cooking meals and running the household budget. In our effort to modernise, we’ve erased homemaking altogether.

I’d like to bring the contest back. I’ll go with ‘Homemaker of the Year’ — the title it took on in its last years. Men can enter — the few who run the home primarily. I’m deadly serious. I think we should bring back awards for people in the home and the work they do — the outrageously challenging work of carrying the load. Given our economic model, contestants will mostly consist of women who are also working outside the home.

Let’s hear more about what they do, not less. Let’s really see them.

If we celebrate people who run homes and hold careers at the same time, we might see it for what it is — exploitation. As another contestant says in the show, back then — “there was enough to do without ever having to go out to work”.

Now, women have two jobs. And so, we have a new and carefully protected form of exploitation — one we keep incredibly quiet. Only the flavour of the dogma is different: It is not religious but economic.

All over Ireland, women are exploited by capitalism and silence. Picture a woman for me, because it usually is a woman: She has three children and works part-time, three or four days a week. She cares for her parents. She’s married to a good man who drops the children to childcare and school and, at the weekend, makes the meals.

She collects them from school on her day ‘off’, along with managing the clothes washing, the daily cooking, the birthday presents, the parent Whatsapp group, her friendships, their two families, and all family holidays, communions, confirmations, and medical appointments. She shops for clothes and everything else. He shops for food — she writes out the list.

This woman absolutely deserves an award for the work she does. But we deem an award for this kind of thing as backwards and demeaning. In truth, what is expected of her is demeaning.

It’s not that men are useless — it’s just that our expectations of them are so low. Men have changed — no doubt. They’re no longer (quite so commonly) rogues and misfits. They make dinners and collect the kids. They still do the DIY. They do their fair share of the children’s activities. Some coach — no small task at all.

But in most households, it is the woman telling the man what needs to be done. The woman is the administrator, the commander in chief, even though she is also expected to have a career. Women laugh it off as if it’s reasonable. It’s not reasonable.

People are living longer, which means more will be expected of our daughters coming up after us — unless we wake up and question it.

So I say — bring back the Homemaker of the Year award. Ask for homemakers to enter who believe they are doing more than is possible for a single human being.

They can be full-time stay-at-home parents, or they can straddle work and home life — anything goes. They can be men.

Get them to compete with one another, boasting over their 16-hour days when they take about an hour to get from the kitchen to the bed because of all the small jobs they must do while their partners snore on, oblivious.

An award is only fitting. If you’re on LinkedIn, browse through all the professional awards people are given. In every town and city in Ireland we heap awards on professionals. No mention is made of the people who devote their lives to their children and their homes, whether it’s on a part-time or full-time basis. We allow for Home of the Year though. So long as the work just happens, it’s permissible.

We have all sorts of ‘professional’ men on television praising gardens, homes, and dinners. It’s just the homemakers, so often women, who have disappeared. The work just happens.

The work doesn’t just happen.

There’s nothing as hard as being a housewife, one woman says on the RTÉ documentary. I would say there is — it’s harder being a housewife or a homemaker when the role is no longer acknowledged or celebrated.

The motif running throughout the documentary — of women standing on stage in an empty auditorium — is perfect.

It reminds me of that article we failed to remove from our Constitution about women’s duties in the home. We voted not to remove them because we rely on them. Irish society knowingly exploits women. We need their duties; we just can’t mention them.

As with every type of oppression women endure, we see but we don’t see. Such is our way.

• '.