Mick Clifford: Housing crisis deepens as homeowners block developments to ‘protect character’

It is beyond doubt that the first instinct of most homeowners when a new development is proposed in their area is to object.

On one level, you might be tempted to say Jack Chambers has some neck. Last Wednesday, the minister for public expenditure wagged a finger at people who objected to new infrastructure and housing. In particular, he hit out at those who objected to development on the basis it undermined the “character” of their area.

“There’s too much tolerance for this in how systems are designed. I’m seeing examples in recent months of housing getting stopped because it undermines the character of the area. What does that mean?” he said.

“For me, it’s about housing, it’s about infrastructure, and cutting through some of the nonsense which is just impeding the broader economic and social objective.”

A repost from homeowners might be that such an observation is rich coming from a politician who, in 2019, objected to two housing developments in his constituency. One was “entirely out of kilter with the existing landscape”, and the other was “out of context” with the area, he wrote.

On Thursday, his spokesperson told his view had evolved over the last six years and now “he makes a conscious effort not to make such observations”.

Well, let’s cut him a little slack and accept he now understands how serious is the housing crisis and is acting accordingly. If so, he was entirely correct to wag his finger at an issue that dare not speak its name among a large cohort of homeowners.

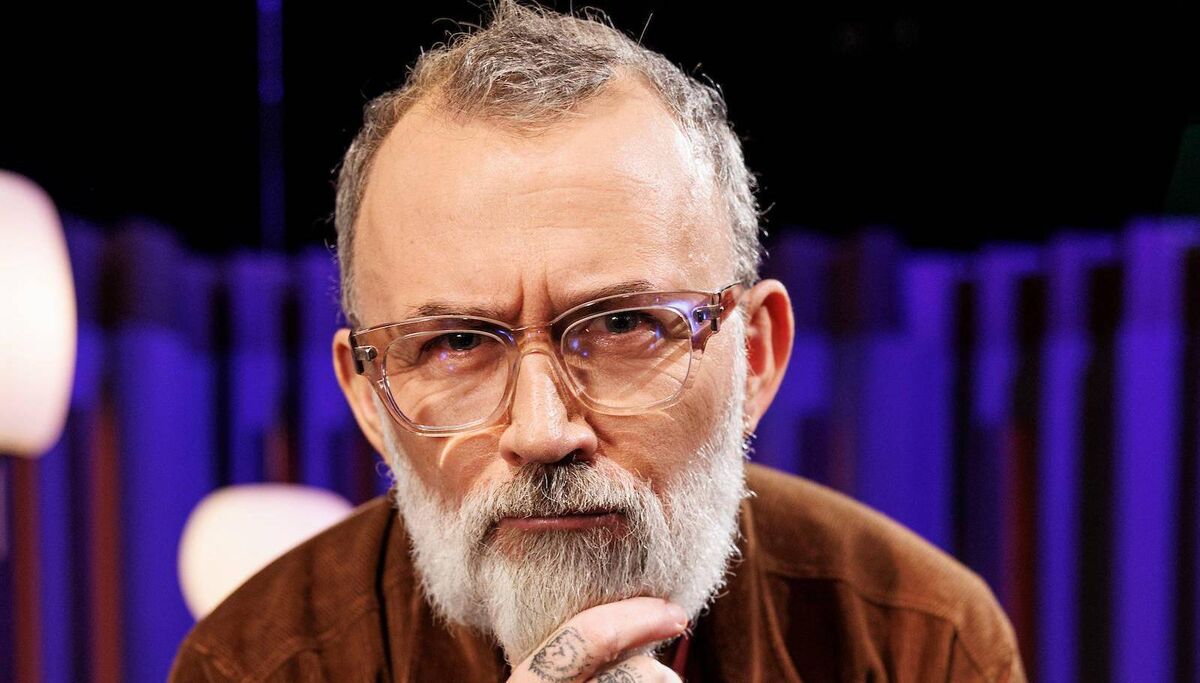

Here are some examples from just the last couple of weeks of the kind of objections that are customarily lodged. Tommy Tiernan was among people who objected to a much-needed wind farm 5km off the coast of Connemara, near Carna, where he lives.

“Culture is judged on how it protects areas and ideals such as this,” he wrote. “Allowing such a project to go ahead when there are many more suitable sites either much further off-shore or inland would be a totally irresponsible and disgusting thing to do.”

Acknowledging a piece of infrastructure is required nationally but would be much better suited elsewhere is frequently referenced in objections.

In Dublin’s salubrious suburb of Killiney, Bono’s wife, Ali Hewson, was among dozens who objected to a proposed development of four new houses.

“We are concerned that this development, by way of its very modern style, flat roofs, and its use of materials could be significantly out of character with the prevailing architectural styles of the surrounding properties,” she wrote.

“We feel that this development, by introducing modern housing in such close proximity to Montebello House, would significantly alter the character of its setting.”

As it turns out, the local authority rejected the development, but not on the basis of objections, but because it should have included more houses.

In north county Dublin, the Land Development Agency, a key player in attempting to ramp up housing, has applied to build 40 duplex units for social housing.

Among the objectors is the Kinsealy Community Organisation, on whose behalf Seán Crawford wrote that “building more houses is not the answer — it’s about creating sustainable communities that can truly thrive”.

He went on to note the proposed duplexes would “violate the area’s rural character”. The rural character of countless areas in commuting distance from towns and cities have been altered due to population increase, but does that mount to ruination?

Meanwhile, in another salubrious enclave, Pembroke Road in Dublin 2, there are conniptions about plans to develop the site of the well-known pub Smyth’s into five storeys of apartments.

Among the objectors is local resident John McBratney who wrote, “I believe in city living… it has been a marvellous place to live, notwithstanding the changes in the streetscape in the intervening years. The proposed development would radically change what is known as Smyth’s pub.”

He described the plan as one which stood to “seriously injure my enjoyment of my home”.

Objecting to — or, as it is termed, submitting an “observation” on — a planning application can in some instances amount to a public duty. Developers, or public bodies, can propose to build structures that are inappropriate, ugly, inconsiderate of the area’s needs, or just damn wrong. Planners are trained to apply principles and practices but they are not infallible.

There are places, for instance, where a four- or five-storey block of apartments would be perfectly acceptable to the surrounding community, but maybe six or eight storeys is proposed and changes the whole tenor of the application.

Serious questions also surround the planning system, particularly regarding genuine consultation, and even collaboration, with the public where possible. The system, in some respects, can appear to be developer-led rather than dictated primarily by the public interest.

And there are instances where infrastructure like onshore windfarms may have a direct impact on matters like health.

But beyond all that, surely during an alleged emergency there is a balance to be struck between what is tolerable for those who are in situ, and what is needed for those who are either looking for a home, or for the supporting infrastructure.

There is scant evidence most homeowners have any consideration for such a balance and instead view all proposals as a threat to what they consider a way of life to which they are entitled.

The political system also has much to answer for in this respect. With notable exceptions, most politicians are willing to parrot objections rather than challenge them in the name of the public good.

Jack Chambers is not alone in apparently modifying his attitude in recent years, but there are still plenty who have no qualms about how to exercise their mandate at a time of emergency.

Privilege is a loaded term. Very often it is used as a weapon in areas like identity politics. Many would bristle at the notion that their own circumstances could be described as privileged, people, for instance, who have worked hard all their lives in order to pay for their home.

Yet in a society where there is a huge chasm between the homeowners and the hopeless wannabes, surely there is a point where the former cohort pause and accept they are in a privileged position in today’s world.

And maybe then they will show some character when it comes to determining whether or not to object instinctively to housing for others.