Elaine Loughlin: Ireland is dangerously exposed to sabotage beneath the sea — and we’re not ready

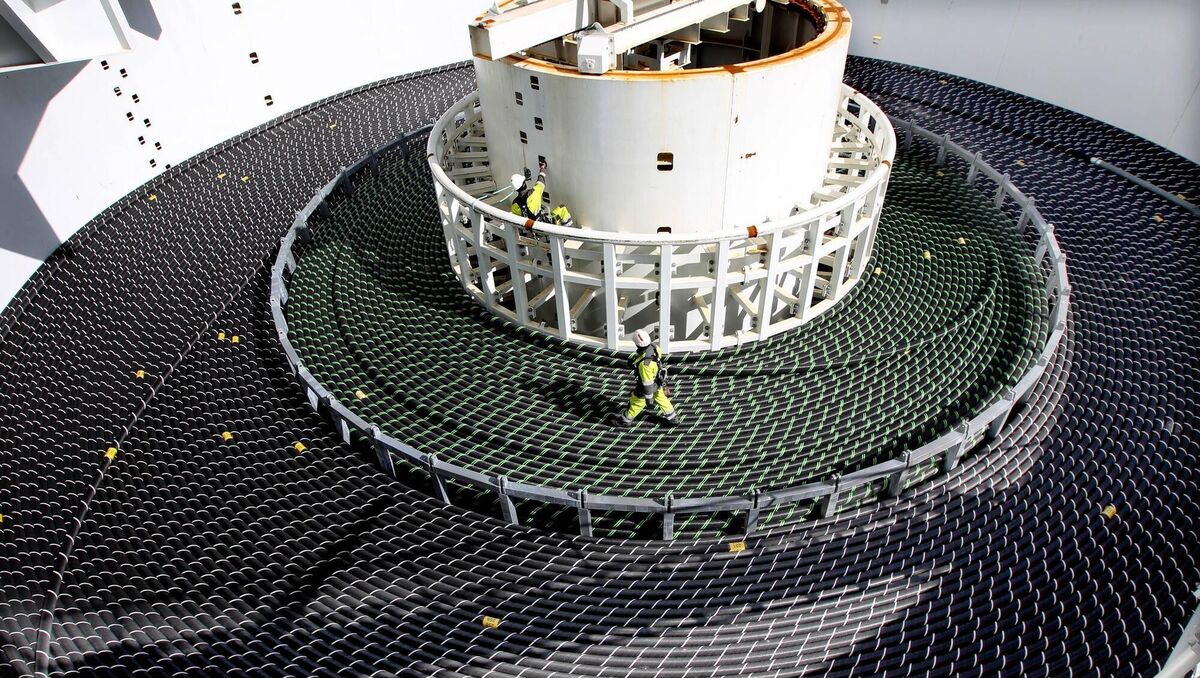

In 2026, this site in Youghal, Co Cork will become the Irish end of the Celtic Interconnector linking the Irish and French electricity networks — just one of Ireland's myriad electricity, gas, and internet links to the world. Picture: Dan Linehan

In the deepest depths of our oceans, hundreds of tiny hollow tubes not much bigger than a garden hose carry information that powers the globe.

In the Dáil this week, Malcolm Byrne highlighted a number of instances over the past two years of Russian vessels operating within Irish waters.

He gave the examples of two Russian-flagged ships, the Umka and the Bakhtemir, that were detected off the coast of Galway in April 2023, while in May of that year four Russian naval vessels including the Admiral Grigorovich, a warship armed with cruise missiles, were located in Irish waters.

BOOKS & MORE

Check out our Books Hub where you will find the latest news, reviews, features, opinions and analysis on all things books from the Irish Examiner's team of specialist writers, columnists and contributors.