Michael Moynihan: Chaos of 1985 reminds us that Cork is in a far better place now

Bodies from the Air India Flight 192 air disaster on June 23, 1985, in a temporary morgue in Cork. Picture: Denis Minihane

The urge to look back is understandable these last few days: a year ending in 5 offers an obvious half-decade hook. When you consider where we were in 2020, a pandemic on the horizon, it’s clear just how quickly things can change.

Go back further and there are even more changes to be found. In recent days there’s been a focus in these pages on Cork back in 1985, with good reason. When I wrote a book about Cork in the eighties, ’85 seemed to be the year when everything came to a head, and the title of the chapter needed just one word: chaos.

Forty years ago Cork was in deep trouble. Huge job losses in the previous eighteen months meant thousands of people were out of work — as Mick Clifford pointed out here recently, at the time Cork TD Denis Lyons told Dáil Éireann that in 1981 Cork’s unemployment rate was 8.6%. By 1985 that rate had doubled to 17%, while in the city itself unemployment had gone from 12% to 21%. As a comparison, during our most recent recession there was consternation when our national unemployment rate was just over 14%.

The city made an impression on the international stage as well, often for the wrong reasons.

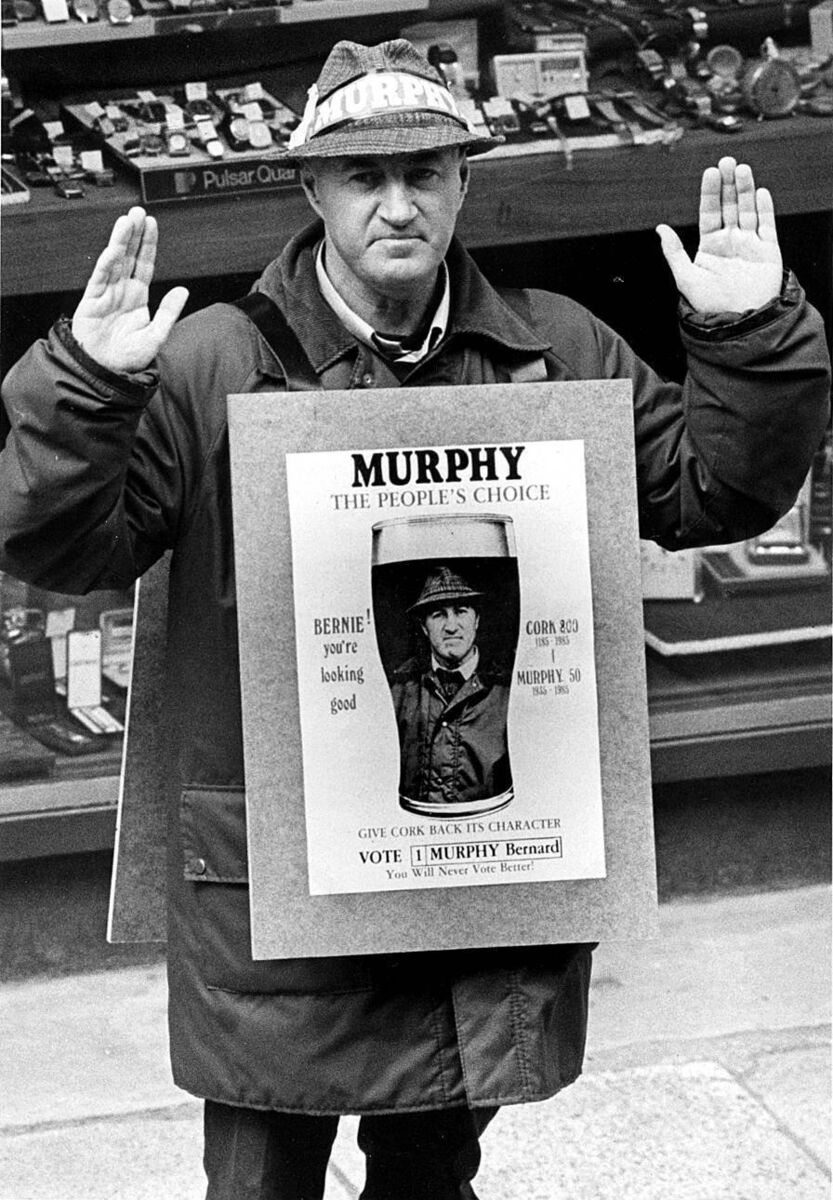

On June 21, 1985, there were local elections in Cork, and Bernie Murphy was elected to the city council. Two days later, Air India flight 132 went down off the west Cork coast with the loss of all 307 passengers and 22 crew.

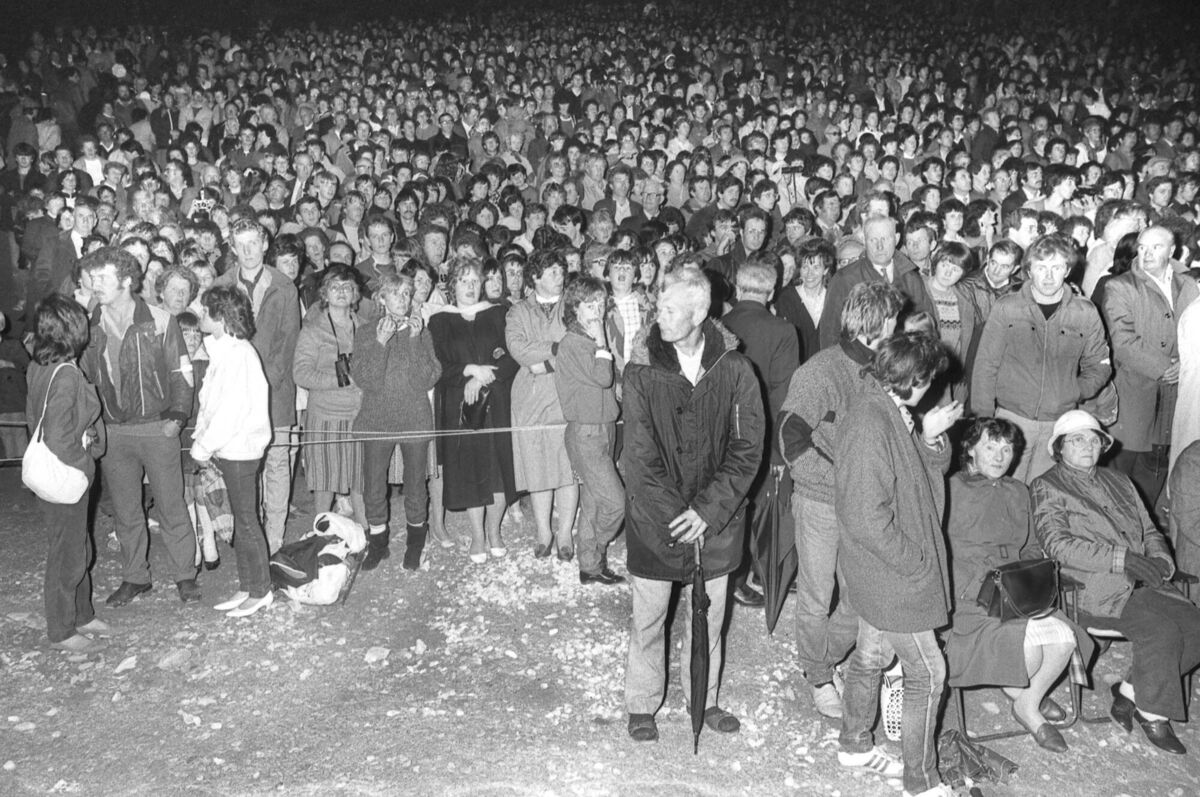

The following month reports emanating from Ballinspittle, near Kinsale, suggested a statue of the Virgin Mary in the local grotto was moving, with thousands coming along to see the phenomenon for themselves.

It’s interesting now to look back and see how those events were represented. The election of Bernie Murphy could be construed, at four decades’ distance, as some kind of protest against the status quo, a registration of unhappiness with the political system.

In fact, it was an opportunistic stroke, with Murphy — an illiterate sandwich board carrier and character around the streets of Cork — used cynically by others to score a cheap political point. When yours truly wrote his book this was the one incident which united all contributors, who condemned what they saw as the exploitation of Bernie Murphy.

California took a keen interest in his electoral success, with running a photograph of Murphy frying sausages in his digs, while the flew him out to the Bay Area, where he gave a speech that lasted all of thirty seconds.

The Air India crash was caused by a bomb, with Sikh separatists eventually blamed for the blast. It was a huge news story at the time, and little wonder — it was one of the biggest terrorist attacks in aviation history up to the attacks on September 11, 2001.

Cork’s ability to handle a major international incident was stretched to the limit, but it met the challenge. The response both official and unofficial earned this letter of thanks from Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, who wrote to the Lord Mayor of Cork five weeks after the crash: “It is with deep admiration that I write to express gratitude to the residents of Cork for the assistance offered to the families and friends of the Air India Flight victims.

“The generosity of time that they have given so freely and their humanitarian spirit have been a true source of comfort to all those who suffered the sudden loss of loved ones. I know that all Canadians share the sense of the overwhelming human tragedy of the victims of Flight 182, but they have also been touched by the way the residents of Cork have opened up their hearts to absorb the grief of this painful human experience.”

Ballinspittle’s moving statue also drew international attention — the BBC took a particular interest in moving statues, as did The New York Times — and while it seemed that there were statues moving all over Ireland at that time, Ballinspittle became synonymous with the phenomenon.

It was a grim year on the sports front for the most part. Cork were under the Kerry boot in Gaelic football and lost the All-Ireland hurling semi-final to Galway in a downpour, while Cork City finished mid-table in the League of Ireland. One of the only highlights was a Triple Crown which Cork won late on against England: Donal Lenihan carried the ball forward, and then Michael Bradley passed to Michael Kiernan for the drop-goal which won the day.

It was a rare win in the capital for Cork. Then-government press secretary Peter Prendergast, discussing Ballinspittle, said: “... three-quarters of the country is laughing heartily.”

The sense that Dublin was less than sympathetic to Cork’s travails was echoed by many of the book’s contributors. They pointed to a lack of awareness in the capital of the disproportionate impact the closure of Ford and Dunlop had on the city compared to somewhere the size of Dublin, which might have absorbed the job losses better. More than one pointed to the mindset that everything should be based and headquartered in Dublin, and there was no shortage of examples to bolster that argument.

For instance, when former UCC President Gerry Wrixon tangled with then-Taoiseach Charles Haughey about the location of a national microelectronics research centre, the politician said it had to be located in Dublin, as the biggest city. Wrixon’s two sentences in response skewered the Dublin-as-default argument then and forever: “If that’s the reason then none of us should live anywhere else. That doesn’t make sense.” In time the NMRC was based in Cork.

Cork is in a far better place now. Credit should go to the likes of Gerry Wrixon for his work with the NMRC, and Larry Poland for his work in getting EMC to Cork, and Dan Byrne for helping to locate Apple in Cork, and dozens of others.

One of the lessons from 1985 which is applicable now — even more so now, perhaps — is not to lose hope. To fight back. Cork has different challenges now but those need to be faced down, not ignored. For the book, I spoke to someone who was a young city councillor back then and remembered the turnaround in Cork’s fortunes. Micheál Martin gave a lot of credit to the education system in Cork as well as the city’s mercantile community: ‘“To be fair to the business people and that community, they didn't take it lying down. They fought back through the chambers of commerce, all of that.

‘“I remember Maurice Moloney, who was assistant city manager back then, saying to me, 'God, Cork has fierce notions of wouldn't it be lovely if we had this.' There were always groups in to see him saying 'we should do this' or 'it would be lovely if we could do that.'”

We still have those notions, of course. Wanting the best for the city has never changed.