Jennifer Horgan: Why do we pretend that biological sex can be easily categorised?

Algeria's Imane Khelif, right, next to Italy's Angela Carini, at the end of their women's 66kg preliminary boxing match at the 2024 Summer Olympics. Picture: AP

For me, one of the most emotional moments of the Olympics came after the women’s 4x400m relay race. Finishing fourth and agonisingly close to the podium, Sophie Becker, Rhasidhat Adeleke, Sharlene Mawdsley, and Phil Healy stood shoulder to shoulder, praising one another.

To be an Olympian is to be superhuman; it involves gruelling hours of training and limitless resilience. These women are incredible, their teamwork, inspiring.

But looking across the four, I wondered, what might have happened if one of them had been considered any less ‘woman’ than other contestants? If one of them had an ounce more testosterone for example, a part-second worth of extra speed, more gas in the tank. Could they have won it? And if so, in that circumstance, could their win have been questioned? Would they have endured the cruelty of online commentators like JK Rowling?

Of course, I was thinking of the boxers.

When Angela Carini left her fight with Algerian boxer Imane Khelif after seconds, many spat their venom.

But then, Carini apologised. No, this was not a case of trans identity — and it never had been. More like a case of an initial, devastated reaction of deep disappointment, and then, a far more complex reality — that biological sex isn’t always straightforward.

I’ve written about this before. The truth is that there are (on estimate) about 40 conditions involving genes, hormones, and reproductive organs that can develop in the womb. Speaking with the BBC, Claus Gravholt, an actual expert, as opposed to a celebrity with an axe to grind, pointed to figures from Denmark as a good indicator of just how common these conditions might be.

“Denmark is probably the best country in the world at collecting this data — we have a national registry with everyone who has ever had a chromosome examination,” said Prof Gravholt

Having chromosomal complications is rare, the professor says, but when looking across the spectrum of issues, about “one in 300 people are affected, based on Denmark’s recorded data.”

Experts also call into question the idea that a simple mouth swab can clear up the mess of it all. Prof Alun Williams researches genetic factors related to sport performance at the Manchester Metropolitan University Institute of Sport. He believes this to be an exceptionally complex situation, one that cannot be solved neatly.

Tests would be potentially “humiliating,” he told the BBC, including “measurements of the most intimate parts of anatomy, like the size of your breast and your clitoris, the depth of your voice, the extent of your body hair.”

As if women’s bodies haven’t been measured and degraded and categorised enough ...

I understand that we are comforted by the simplicity of binaries. I have sympathy for it, but it doesn’t make them factually correct.

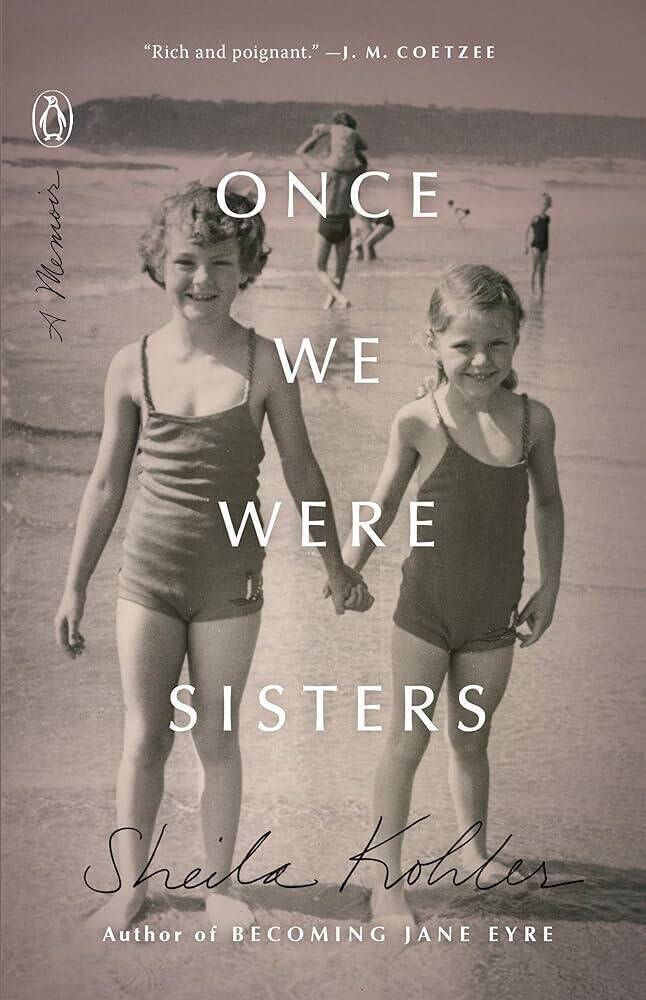

I’m reminded of a book I read recently, a memoir by Sheila Kohler, called .

Kohler includes a fascinating detail about how authorities categorised people by race during apartheid. Between 1948 and 1994, a pencil was pushed through the person's hair. If the pencil stayed, you were Black. If the pencil slid through, you could be considered white. If it fell out when you shook your head, you could be classified as mixed (‘Coloured,’ in South African race classification).

Are we really willing to rush forward with similarly simplistic testing in sport, without the consensus of the scientific community, to pretend that biological sex is so easily categorised?

It seems some are. Many look to an earlier disqualification of the two fighters involved, Khelif, and Taiwanese boxer Lin Yu Ting, as proof of wrongdoing by the Olympic Committee, for clearing both to compete in the women's boxing in Paris. It is true that they had been disqualified from last year's Women's World Championships for failing to meet unspecified eligibility requirements in a biochemical test, but the IBA said the test’s “specifics remain confidential,” refusing to explain it.

Two things strike me about this deep and arguably disproportionate concern for the opponents of these two boxers. Firstly, boxing is inherently dangerous. It is officially the toughest sport in the world according to a dataset by ESPN published in 2023. It is the worst sport in terms of long-term head injuries. According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 90% of all boxers sustain a traumatic brain injury in their careers.

But if I am going to defend a minority of people with complex conditions relating to biological sex, then I should also defend elite female boxers, right? Yes, absolutely. I take the point.

However, unfair natural advantage has always characterised elite sports. Is it unfair that I watched the Olympics from my couch because I lack any shred of physical prowess? Isn’t that the stuff of sport? Usain Bolt should never have been both so tall and yet so fast. Tiger Woods should never been able to hit the ball so far. Maradona and Messi should never have managed to be so small, and so dazzlingly skilful. Athletes have broken the game again and again through the lottery of natural assets.

Look at Serena Williams, another elite female athlete dogged by criticism along the same ‘excessive testosterone’ lines. Did her high testosterone levels give her an unfair advantage? Or is such close policing of female bodies another way to limit women’s sport? To narrow the field? To dilute it into blandness?

Remember, this is not about trans identity. Tennis legend Martina Navratilova is vocally against trans women competing in women’s sport, but is hugely supportive of Caster Semenya, the South African who suffers from a condition called hyperandrogenism, characterised by heightened testosterone levels.

“She has never sought an advantage,” Navratilova has said.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, it is not always about the dog in the fight; it is about the fight in the dog. Natural strength is not always an indicator of success, even in an utterly brutal game like boxing. Muhammed Ali should never have beaten George Foreman after all. He was older and not as strong. The bookies favoured Foreman. But Ali floated like a butterfly. Around the colossus, he stung like a bee, thereby making history.

The callous reaction to Imane Khelif and Lin Yu Ting, particularly online, is far more to do with a determined ignorance about biological sex than anything else. We should all be in a holding pattern, holding our position, our breath, waiting to know and understand more. Kindness is key.

And we should be kind and respectful to all Olympians who have worked harder than we can imagine, just as our own Olympians have. At least, that is, until we know what the hell we’re talking about.

If, on the other hand, it’s male violence we want to talk about, we should talk about male violence. There is plenty of it around. In the same memoir I mentioned, , Kohler shares her belief that her big sister was killed by her husband, a story tragically replicated this week with a woman in Malta reportedly having been killed by her Irish partner. A story replicated last week too, with the murder of a young woman in Cork. Too many women killed — by true villains, by truly violent men.