Sarah Harte: McGahern leaves us pondering what we have lost and gained

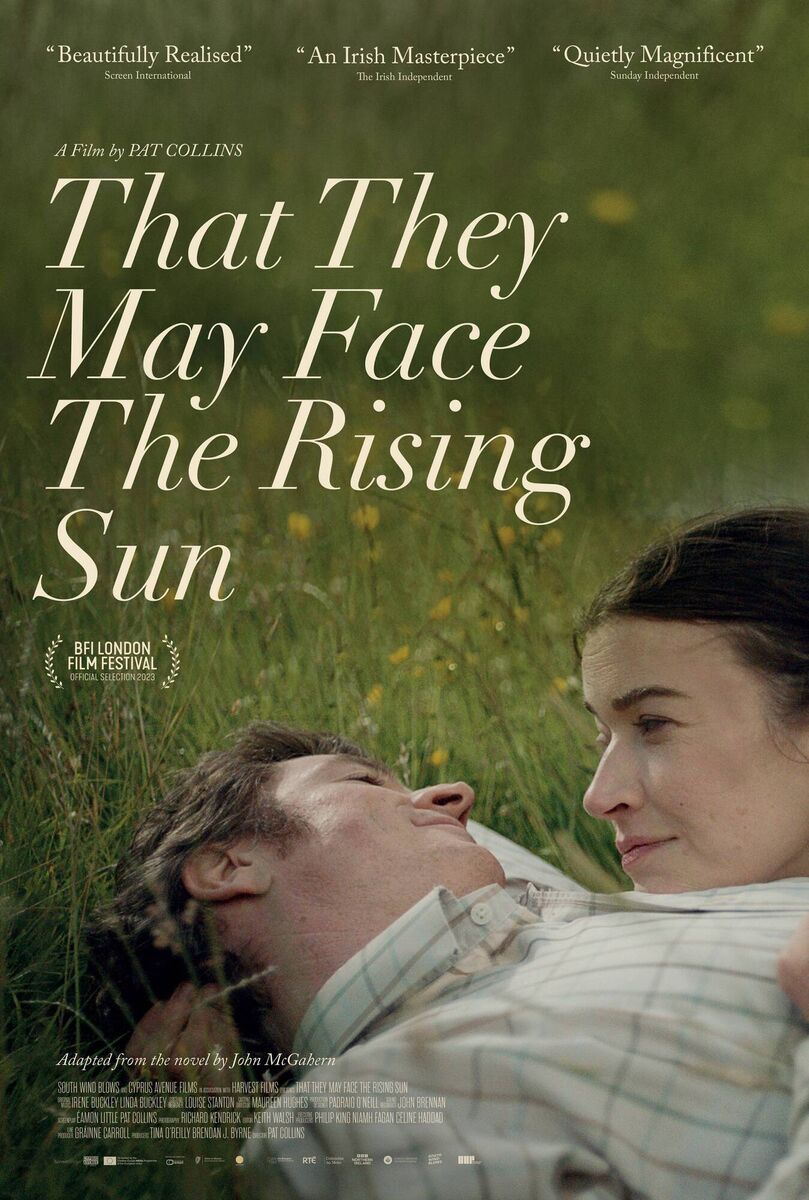

A scene from 'That They May Face The Rising Sun'.

ow times have changed. Director and West Cork man Pat Collins’s film , adapted from John McGahern’s powerful novel, is set in early 1980s rural Ireland, but it may as well be a different country. Watching the film is like stepping through a looking glass. It will scoop you up like a warm hug, and at other times it will break your heart.

People wear proper clothes, nobody is encased in athleisure wear which is a welcome relief, cars include a Volkswagen Beetle and Ford Cortina, a telephone service is about to be put in, but people write letters, neighbours knock on doors and visit each other, they drink drive, attend mass, and have a thirst for news in a place where local goings-on are of more import than the outside world.

These are the men and women who took the boat in droves in the second half of the 20th century, to find work, and to flee institutional abuse. Many of them made huge financial and emotional sacrifices to send home valuable remittances but had nowhere to come back to.

Patrick takes to the bed when he is depressed. A man of exceptional intelligence who like many of the characters didn’t get their chance, his thwarted intellect twists and bends.