Terry Prone: Most powerful tool to owning the outcome is communication

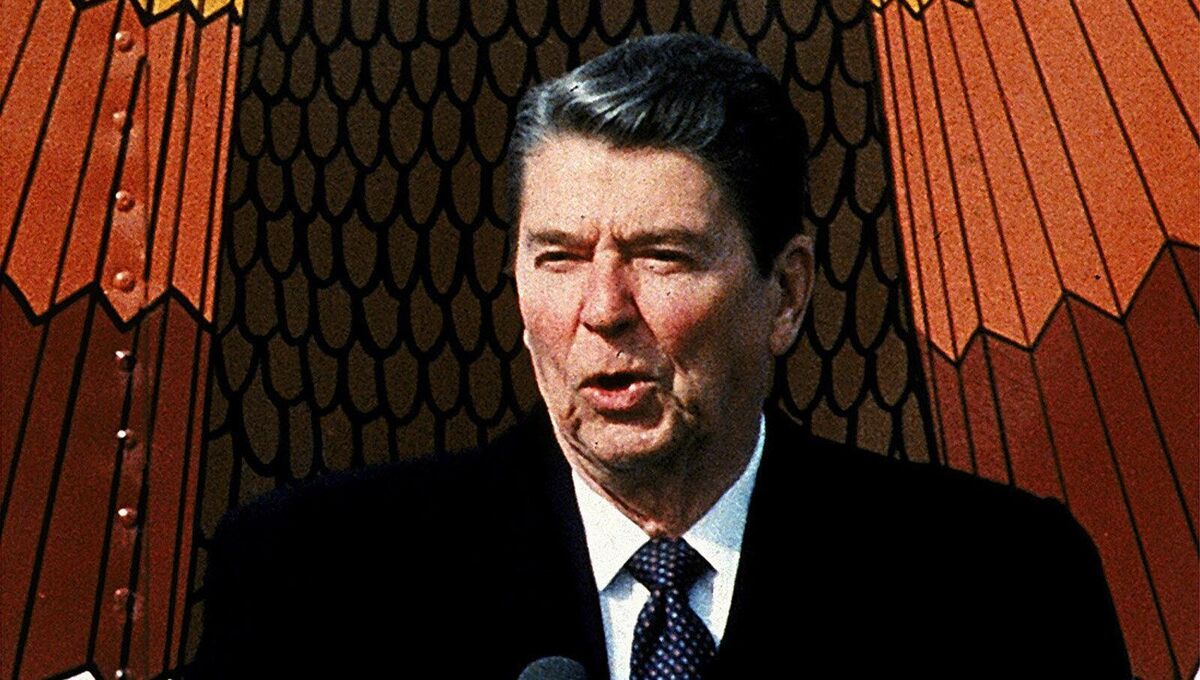

Former US president Donald Trump can thank another former US president Ronald Reagan for weakening the ‘Fairness Doctrine’ — a protective fence around public information.

Reagan changed everything in a way that was not fully appreciated at the time.

Broadcasting history, like medical history, tends to major on the heroic intervention that generated massive change. In medicine, one of those heroic interventions was the introduction of antibiotics. In broadcasting, it was the arrival of a knight in shining armour, like Ed Morrow, who in one broadcast holed the fascist Joe McCarthy below the waterline. Here, although less deified, The Late Late Show served, in a more diffuse way, something of the same function, facing down prejudice and permanently weakening the power of the Church in Ireland.