Fergus Finlay: Abuse will happen when abusers believe they can act with impunity

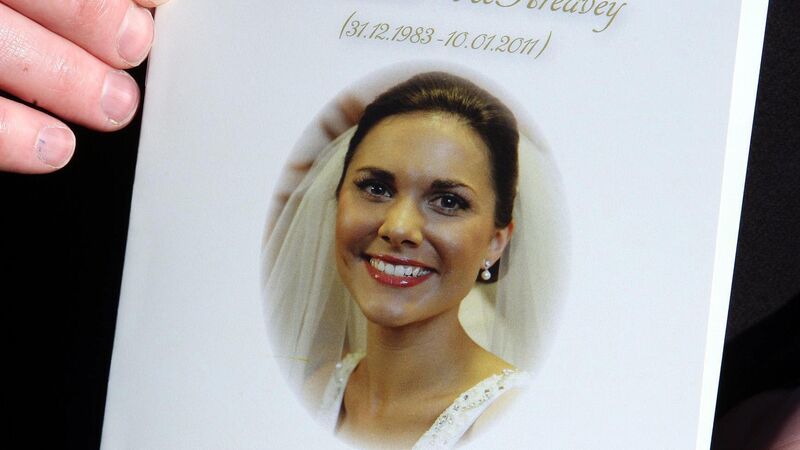

The death of Michaela McAreavey was made fun of for one reason and one reason only. She was Catholic. It was viciously sectarian.

SO tell me, when did domestic violence become prime time entertainment? When did the murder of a young woman become fodder for bigotry and sectarianism? Why was it so important — and unusual — for so many of us to applaud the sentences handed down by a judge in a rape case?

In the murk and grime of some of the events of the last week, one woman’s bravery stood out. And she was a victim — the victim of a vicious assault by a group of five young men, inflicted on her as if she was an object and not a real person.

“First it took the internal parts of me — my dignity, my innocence, my trust, my self-worth. Then it started taking my external parts. My education fell apart, my social skills, my friendships dwindled, and isolation crept in.”

That’s how this brave young woman described the effect of a gang rape on her. And speaking to the men who had attacked her, in her victim impact statement, she told them directly: “You give me no reason to address you. All of you have made me feel like I wasn’t even a human being.

It is you who are sub-human — how could you take pleasure in doing something so horrific to another person?

It’s the question I can’t get out of my head. This young woman doesn’t want her name known, and she’s absolutely entitled to her privacy. But I would love her to know that there are many people who know her as a real person and not as the object of anonymised newspaper reports — as a brave independent person who deserves a full and happy life, and whatever resources and support she needs to get there.

I find myself thinking about the young men involved too. What can have enabled such barbarism as was played out in that trial? How could they have egged each other on? How come there wasn’t even one to shout stop?

Consent

In handing down sentences, Judge Tara Burns addressed the lie peddled by the defence that there had been consent involved.

“Women are not playthings,” she said. “Consent is not a decision for the perpetrators. Because a woman doesn’t call out or fight does not mean she is consenting. How was she to know what would become of her if she fought back or attempted to escape?”

Everything the judge said in the case was exactly what you would hope or expect. The sentences were what they needed to be. Her comments about the perpetrators and the victims were entirely appropriate.

Yet it was also remarkable — worthy of notice because of its directness and honesty, almost its simplicity. And for its clear assertion of the core principle of consent.

For some reason, it’s far more common in Ireland for judgments — especially in cases of sexual violence — to be attacked because of their leniency. And the consent argument is still the one most often relied on by legal defences. Lawyers know if they can undermine the credibility of the victim in relation to consent, their clients have a much better chance of going free. What defence lawyers want to plant in the minds of judges and juries is the thought that “she didn’t say no” is the same as “she said yes”.

The men in that car that night must have known that nothing they were doing involved consent at any level. One of them at least, you have to believe, must have known what was happening was terribly wrong. Yet not one of them had the strength of character to make it stop.

Michaela McAreavey

And no one shouted stop in an Orange Lodge last week when, in the course of “celebrating” the centenary of Northern Ireland, a group of men sang a disgusting chant about the murder of Michaela McAreavey to a crowded room where everyone seemed to know the words.

Nobody stopped to wonder how you could possibly turn a terrible crime into a rancorous chant. Instead, as some of them sang, punching the air like a particular kind of football supporter, the rest clapped and cheered and banged the tables.

It was viciously sectarian. The death of Michaela McAreavey could be made fun of for one reason and one reason only. She was Catholic. And, of course, that sort of sectarianism isn’t confined to one side.

A few years ago a Sinn Féin MP (who was forced to resign) made fun of 10 murdered (Protestant) textile workers as a “celebration” of the anniversary of the Kingsmill massacre.

But in the bits of the Orange Order video that are still visible, it’s clear that the audience is almost entirely male, most of them in white shirts and ties, and all completely absorbed in enjoying a recitation about an act of violence against a young woman.

It was as misogynistic as anything I’ve seen recently. It’s clear that no one in that room had the manhood to see how ugly they were. You might have to forgive me for using the word manhood. I can’t think of a better word, just as I can’t think of any definition of that word that allows a man to glorify violence against a woman.

Amber Heard and Johnny Depp

In a strange way though, the thing that perplexed me most in the last week was the seemingly endless global fascination with the Johnny Depp/Amber Heard trial. And not just fascination, but the extraordinary taking of sides.

Apparently, it was part of the legal strategy in the case to whip up public opinion. And so we were all invited to immerse ourselves. What we all forgot in the process was that this was a case about domestic violence. Although it was fought as a defamation case, each side essentially sought to prove that the other party was the violent one.

Depp lost in the UK and won in the US, bizarrely enough. Despite their respective fan clubs and social media “teams”, none of us will probably ever know the real truth.

But there was one real loser in the case. The issue of domestic violence itself. It was played out for titillation and ratings over several weeks on worldwide television, in front of an audience that seemed to forget entirely how corrosive an issue this is.

When violence enters any relationship, it sometimes happens as a way of asserting power and control. It is always exacerbated by an imbalance of power. In the great majority of cases, although not in all, the balance of power lies with the male side of the relationship. And it always happens behind closed doors, because abusive power likes it that way.

So there is some merit in seeing it exposed on television, but never in the trivialised sensationalised way that it was covered in that trial. Sure, people took sides right from the off, but that’s nothing like the same as saying we know the truth now.

The truth is abuse happens when power is abused. It happens when free and open consent is denied. It happens when people are treated as less than human by other people. And it happens most when people believe they can act with impunity. They’re the things that have to change.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates