Michael Clifford: Brown envelopes and Bob Dylan's genius livened up planning tribunals

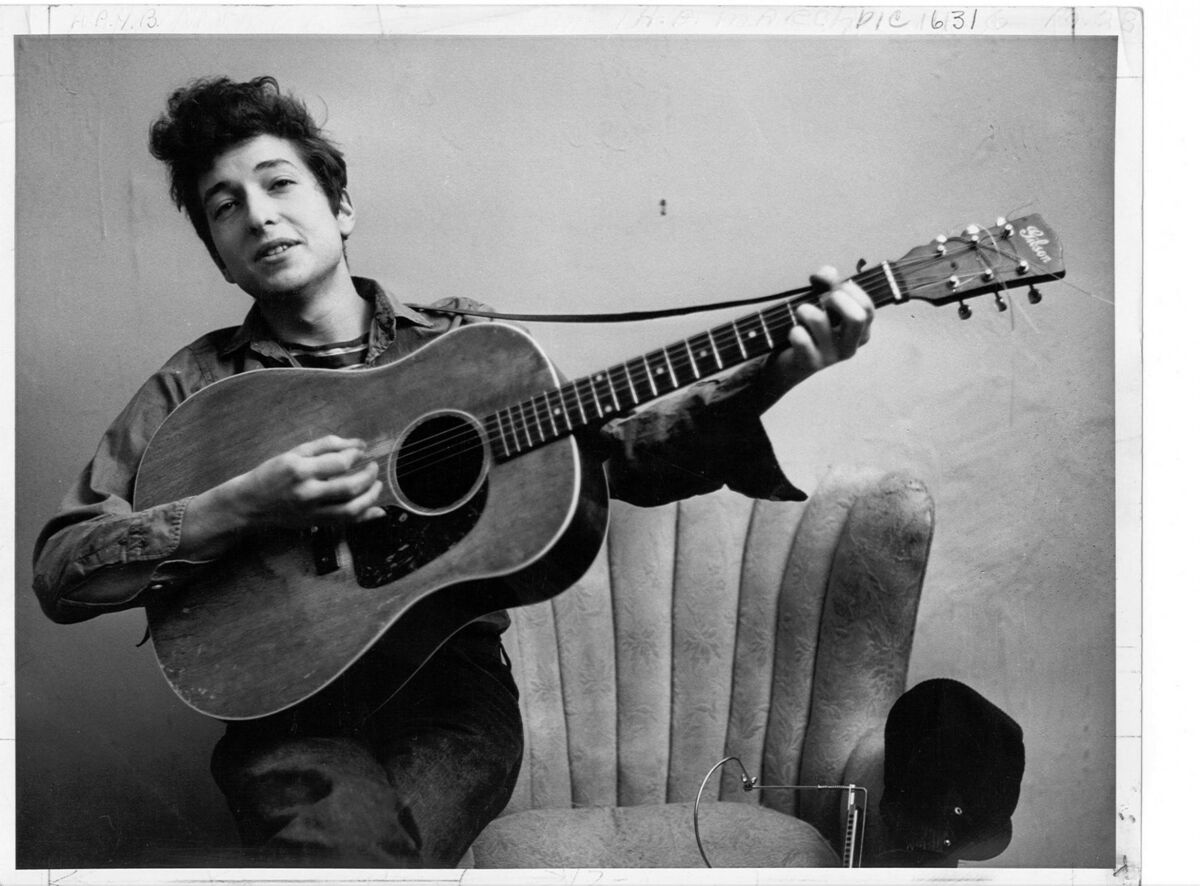

There has, in recent days, been much expanding and expounding on the significance of Bob Dylan’s impending birthday, his contribution to culture, his mysterious ways and enduring appeal. Photo: HO/AFP/Getty Images

We had some craic the day Bob Dylan showed up at the planning tribunal. Well, I did anyway. The self-styled song and dance man turns 80 on Monday so maybe it’s time to come clean about his input into tales of dodgy rezoning and brown envelopes.

There has, in recent days, been much expanding and expounding on the significance of Dylan’s impending birthday, his contribution to culture, his mysterious ways and enduring appeal. All I can bring to the table is a lifetime of love.

When he pinged onto my early teenage radar I was battling acne and he was already embarked on his second career. His first involved being the reluctant voice of a generation and a seer for the 60s, a period during which the zeitgeist spilled from his guitar and pen as if he was a medium installed to sort things out.

Then he had a motorcycle crash which he was lucky to survive. If that incident had taken his life he would have joined the pantheon of musicians from Robert Johnson through to Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Amy Whitehouse, their immortality secured through dying young while living fast.

He retreated to upstate New York with his wife and children and did the family thing for a few years. By the early 70s his marriage was falling apart and he produced one of his greatest works, the album . In an interview soon after its release, a reporter gushed about its brilliance. “How can you enjoy so much pain?” Dylan replied.

It was a few years later that we met up, me having commandeered the family record player and removed it to my bedroom, he singing through an album of greatest hits on a borrowed LP. As far as my ultimate preferences are concerned, he hadn’t yet written his greatest hits by that time.

He has ever since those days been in my head in one form or another, his voice, “like sand and glue” as David Bowie described it, his words, phrasing and music exercising a hypnotic pull. I can go weeks without hearing it, but then a song comes on the radio, setting off some demented process, pulling me back in.

The first LP I ever bought was Dylan’s , a good album, but not a great album. A few months back and over 40 years down the line, I heard a cover of one of the best songs on it, 'Senor'. All hell broke loose. I was off immediately to the great Satan Spotify to sit and listen to the album start to finish, transporting me all the way back to acne, confusion and the annoying mystery of girls.

The acne was receding when I first saw him in concert at Slane Castle in 1984. He appeared in a long frock coat and boots reaching above his shins, as if he had just emerged from his abode in a forest in north county Meath to sing a few old songs. That day, he brought a young Bono on stage, and from our spot on the hill we were petrified that the U2 man was going to disgrace us in front of Bob.

To be fair, in a famous interview recorded in a New York hotel room a few months later, Dylan gushed about this Bone-o guy who joined him onstage in “Dublin”. The purists weren’t impressed with the Slane gig, but the purists would probably have said the Blessed Virgin was a bit reticent when she dropped into Medjugorje.

All that mattered was Dylan had appeared.

Down the decades I shadowed him, through good albums and a few mediocre, at some first-class concerts and, even I have to admit, at a few that were touch and go. In 2006, he released , an album that ranks among my own favourites.

Outrageously, he was 65 years of age then, a time in life when most contemporary musicians are having to reach back at least three decades to find their creative peak. Where would you get it?

Anyway, about that day he showed up at the planning tribunal. I was at the time detailed by the to write a weekly account of the goings on related through sworn evidence of dodgy politics and dodgy planning.

Included in the narrative were a cast of characters who might have made it as extras in . Despite that, there were some spells during which the evidence could bore for Ireland. So it went the week Bob showed up.

I arrived back at the newspaper's office on the Friday and sat down to write a piece about bank accounts and brown envelopes and meetings that nobody could remember but I never will forget. Still, it had been a poor week by normal standards.

What could I do to save dull copy? Then it came to me. Write a piece including as many lines from Dylan songs as possible.

This was a week for anoraks only. Nobody else would read the damn thing. So I constructed a narrative about the evidence that had been heard about these low standards in high places.

The internet was not around in those days so I don’t have a copy of the piece, but from memory it included phrases like “Meanwhile, far away in another part of town” ('Hurricane'); “Their minds were filled with big ideas, images and distorted facts” ('Idiot Wind'); “The only thing we knew for sure about Henry Porter (insert here signature on dodgy cheque) is that his name was not Henry Porter.” ('Brownsville Girl'); “The conversation was short and sweet” ('You’re a Big Girl Now').

“He’s got a lot of nerve” ('Positively Fourth Street', including a planning licence to substitute “You’ve” with “He’s”). There was more, and from memory I finished with a line from 'Sweetheart like You'. “Steal a little and they throw you in jail, steal a lot and they make you a king.”

Nobody in the editorial process spotted it, which as far as I was concerned meant my secret was secure. None of the handful of anoraks who would read the piece on a slow week would have a clue about Dylan's songs. Or so I thought.

Within days, I received a letter from one of the anoraks, a man in West Cork. He got a great kick out of it but I hid the letter, petrified that my dark manipulations would be exposed. Now it’s all out there, my back pages.

Happy birthday, man. It’s not dark yet and there are miles of road yet to run.