US-made AI empowers Israel’s warfare

Israel’s recent wars mark a leading instance in which commercial AI models made in the US have been used in active warfare.

American tech giants have quietly empowered Israel to track and kill many more alleged militants more quickly in Gaza and Lebanon through a sharp spike in AI and computing services. However, the number of civilians killed has also soared, fuelling fears that these tools are contributing to the deaths of innocent people.

Militaries have for years hired private companies to build custom autonomous weapons. However, Israel’s recent wars mark a leading instance in which commercial AI models made in the US have been used in active warfare, despite concerns that they were not originally developed to help to decide who lives and who dies.

The Israeli military uses AI to sift through vast troves of intelligence, intercepted communications, and surveillance to find suspicious speech or behaviour and learn the movements of its enemies. After a deadly surprise attack by Hamas militants on October 7, 2023, its use of Microsoft and OpenAI technology skyrocketed, an Associated Press (AP) investigation found.

The investigation also revealed new details of how AI systems select targets and ways they can go wrong, including faulty data or flawed algorithms. It was based on internal documents, data, and exclusive interviews with current and former Israeli officials and company employees.

“This is the first confirmation we have gotten that commercial AI models are directly being used in warfare,” said Heidy Khlaaf, chief AI scientist at the AI Now Institute and former senior safety engineer at OpenAI.

“The implications are enormous for the role of tech in enabling this type of unethical and unlawful warfare going forward.”

As US tech titans ascend to prominent roles under president Donald Trump, the findings raise questions about Silicon Valley’s role in the future of automated warfare.

Microsoft expects its partnership with the Israeli military to grow, and what happens with Israel may help to determine the use of these emerging technologies around the world.

The Israeli military’s usage of Microsoft and OpenAI technology spiked last March to nearly 200 times higher than before the week leading up to the October 7 attack, a review of internal company information showed.

The amount of data it stored on Microsoft servers doubled between that time and July 2024 to over 13.6 petabytes — roughly 350 times the digital memory needed to store every book in the US Library of Congress. Usage of Microsoft’s huge banks of computer servers by the military also rose by almost two-thirds in the first two months of the war alone.

Israel’s goal after the attack that killed about 1,200 people and took more than 250 hostages was to eradicate Hamas, and its military has called AI a “game changer” in yielding targets more swiftly.

Since the war started, more than 50,000 people have died in Gaza and Lebanon and nearly 70% of the buildings in Gaza have been devastated, health ministries in Gaza and Lebanon say.

The investigation drew on interviews with six current and former members of the Israeli army, including three reserve intelligence officers. Most spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorised to discuss sensitive military operations.

More than a dozen current and former employees in Microsoft, OpenAI, Google, and Amazon were also interviewed, most of whom also spoke anonymously for fear of retribution.

Journalists reviewed internal company data and documents, including one detailing the terms of a $133m (€128m) contract between Microsoft and Israel’s ministry of defence.

The Israeli military says its analysts use AI-enabled systems to help to identify targets but independently examine them together with high-ranking officers to meet international law, weighing the military advantage against the collateral damage.

A senior Israeli intelligence official said lawful military targets may include combatants fighting against Israel, wherever they are, and buildings used by militants. Officials insist that even when AI plays a role, there are always several layers of humans in the loop.

“These AI tools make the intelligence process more accurate and more effective,” said an Israeli military statement.

“They make more targets faster, but not at the expense of accuracy, and many times in this war they’ve been able to minimize civilian casualties.”

The Israeli military declined to answer detailed written questions about its use of commercial AI products from American tech companies.

Microsoft declined to comment and did not respond to a detailed list of written questions about cloud and AI services provided to the Israeli military. In a statement on its website, the company says it is committed “to champion the positive role of technology across the globe”.

In its 40-page Responsible AI Transparency Report for 2024, Microsoft pledges to manage the risks of AI throughout development “to reduce the risk of harm”, and does not mention its lucrative military contracts.

Advanced AI models are provided through OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, through Microsoft’s Azure cloud platform, where they are purchased by the Israeli military, the documents and data show. Microsoft has been OpenAI’s largest investor.

OpenAI said it does not have a partnership with Israel’s military, and its usage policies say its customers should not use its products to develop weapons, destroy property, or harm people. However, about a year ago, OpenAI changed its terms of use from barring military use to allowing for “national security use cases that align with our mission”.

It is extremely hard to identify when AI systems enable errors because they are used with so many other forms of intelligence, including human intelligence, sources said. However, together, they can lead to wrongful deaths.

In November 2023, Hoda Hijazi was fleeing with her three young daughters and her mother from clashes between Israel and Hamas ally Hezbollah on the Lebanese border when their car was bombed.

Before they left, the adults told the girls to play in front of the house so that Israeli drones would know they were travelling with children. The women and girls drove alongside Hijazi’s uncle, Samir Ayoub, a journalist with a leftist radio station, who was caravanning in his own car. They heard the frenetic buzz of a drone very low overhead.

Soon, an airstrike hit the car Hijazi was driving. It careened down a slope and burst into flames. Ayoub managed to pull Hijazi out, but her mother — Ayoub’s sister — and the three girls — Rimas, 14, Taline, 12, and Liane, 10 — were dead.

Before they left their home, Hijazi recalled, one of the girls had insisted on taking pictures of the cats in the garden “because maybe we won’t see them again”. In the end, she said, “the cats survived and the girls are gone”.

Video footage from a security camera at a convenience store shortly before the strike showed the Hijazi family in a Hyundai SUV, with the mother and one of the girls loading jugs of water. The family says the video proves Israeli drones should have seen the women and children.

The day after the family was hit, the Israeli military released video of the strike along with a package of similar videos and photos. A statement released with the images said Israeli fighter jets had “struck just over 450 Hamas targets”.

Visual analysis matched the road and other geographical features in the Israeli military video to satellite imagery of the location where the three girls died, 1.7km from the store.

An Israeli intelligence officer said AI has been used to help to pinpoint all targets in the past three years. In this case, AI likely pinpointed a residence, and other intelligence gathering could have placed a person there. At some point, the car left the residence.

Humans in the target room would have decided to strike. The error could have happened at any point, he said. Previous faulty information could have flagged the wrong residence, or they could have hit the wrong vehicle.

The AP also saw a message from a second source with knowledge of that airstrike who confirmed it was a mistake, but did not elaborate.

A spokesperson for the Israeli military denied that AI systems were used during the airstrike itself, but refused to answer whether AI helped to select the target or whether it was wrong. The military told the AP that officials examined the incident and expressed “sorrow for the outcome”.

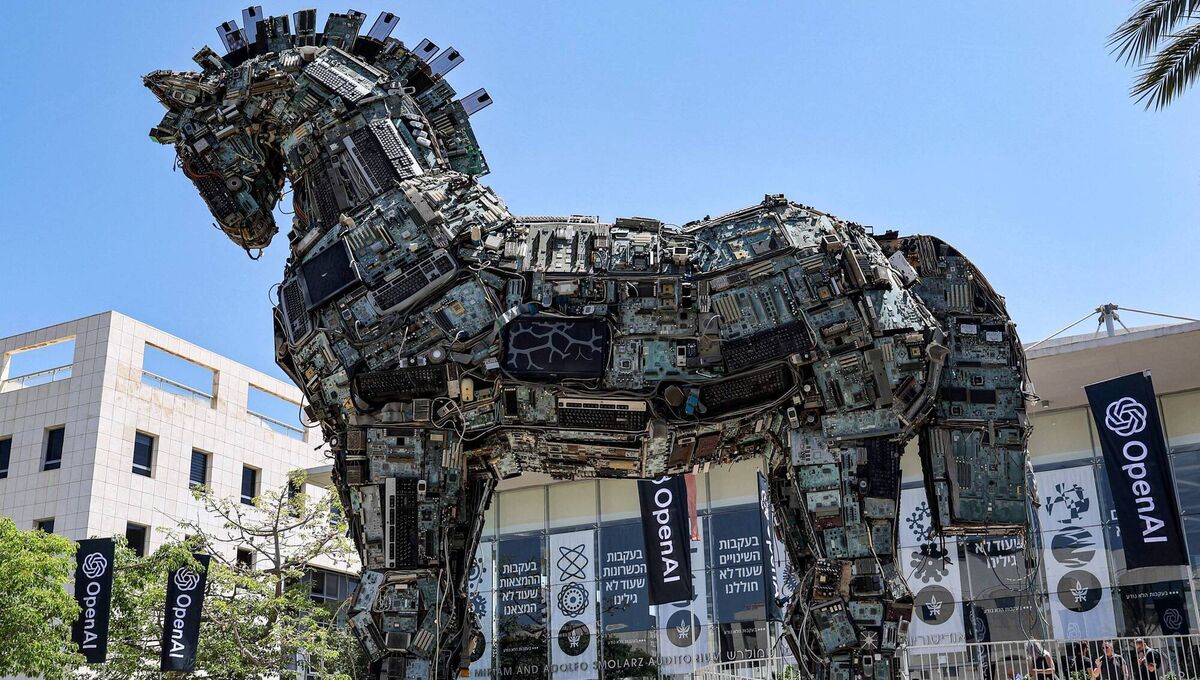

Microsoft and the San Francisco-based startup OpenAI are among a legion of US tech firms that have supported Israel’s wars in recent years.

Google and Amazon provide cloud computing and AI services to the Israeli military under Project Nimbus, a $1.2bn contract signed in 2021 when Israel first tested its in-house AI-powered targeting systems. The military has used Cisco and Dell server farms or data centres.

Red Hat, an independent IBM subsidiary, also has provided cloud computing technologies to the Israeli military, and Palantir Technologies, a Microsoft partner in US defence contracts, has a “strategic partnership” providing AI systems to help Israel’s war efforts.

Google said it is committed to responsibly developing and deploying AI “that protects people, promotes global growth, and supports national security”.

Dell provided a statement saying the company commits to the highest standards in working with public and private organisations globally, including in Israel.

Red Hat spokesperson Allison Showalter said the company is proud of its global customers, who comply with Red Hat’s terms to adhere to applicable laws and regulations.

Palantir, Cisco, and Oracle did not respond to requests for comment. Amazon declined to comment.

The Israeli military uses Microsoft Azure to compile information gathered through mass surveillance, which it transcribes and translates, including phone calls, texts, and audio messages, an Israeli intelligence officer who works with the systems said. That data can then be cross-checked with Israel’s in-house targeting systems and vice versa.

He said he relies on Azure to quickly search for terms and patterns within massive text troves, such as finding conversations between two people within a 50-page document. Azure also can find people giving directions to one another in the text, which can then be cross-referenced with the military’s AI systems to pinpoint locations.

The Microsoft data reviewed shows that since the October 7 attack, the Israeli military has made heavy use of transcription and translation tools and OpenAI models, although it does not detail which. Typically, AI models that transcribe and translate perform best in English. OpenAI has acknowledged that its popular AI-powered translation model Whisper, which can transcribe and translate into multiple languages including Arabic, can make up text that no one said, including adding racial commentary and violent rhetoric.

“Should we be basing these decisions on things that the model could be making up?” said Joshua Kroll, an assistant professor of computer science at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, who spoke in his personal capacity, not reflecting the views of the US government.

The Israeli military said any phone conversation translated from Arabic or intelligence used in identifying a target has to be reviewed by an Arabic-speaking officer.

Errors can still happen for many reasons involving AI, said Israeli military officers who have worked with the targeting systems and other tech experts. One intelligence officer said he had seen targeting mistakes that relied on incorrect machine translations from Arabic to Hebrew.

Intercepted phone calls tied to a person’s profile also include the time the person called and the names and numbers of those on the call. However, it takes an extra step to listen to and verify the original audio, or to see a translated transcript.

Sometimes, the data attached to people’s profiles is wrong. For example, the system misidentified a list of high school students as potential militants, the officer said.

AI alone could lead to the wrong conclusion, said another soldier who worked with the targeting systems. For example, AI might flag a house owned by someone linked to Hamas who does not live there. Before the house is hit, humans must confirm who is actually in it, he said.

Tal Mimran served 10 years as a reserve legal officer for the Israeli military, and on three Nato working groups examining the use of new technologies, including AI, in warfare. Previously, he said, it took a team of up to 20 people a day or more to review and approve a single airstrike. Now, with AI systems, the military is approving hundreds a week.

Mimran said over-reliance on AI could harden people’s existing biases.

“Confirmation bias can prevent people from investigating on their own,” said Mimran, who teaches cyber law policy.

“Some people might be lazy, but others might be afraid to go against the machine and be wrong and make a mistake.”

Among US tech firms, Microsoft has had an especially close relationship with the Israeli military spanning decades.

That relationship, alongside those with other tech companies, stepped up after the Hamas attack. Israel’s war response strained its own servers and increased its reliance on outside, third-party vendors, a presentation last year by the military’s top information technology officer showed.

As she described how AI had provided Israel with “very significant operational effectiveness” in Gaza, the logos of Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, and Amazon Web Services appeared on a large screen behind her.

“We’ve already reached a point where our systems really need it,” said colonel Racheli Dembinsky, commander of the Center of Computing and Information Systems, known by its Hebrew acronym Mamram.

One three-year contract between Microsoft and the Israeli ministry of defence began in 2021 and was worth $133m, making it the company’s second largest military customer globally after the US, a document reviewed by the AP showed.

The Israeli military is classified within Microsoft as an S500 client, meaning that it gets top priority as one of the company’s most important customers globally.

The Israeli military’s service agreements with Microsoft include at least 635 individual subscriptions listed under specific divisions, units, bases, or project code words.

In Israel, a team of at least nine Microsoft employees is dedicated to serving the military’s account. Among them is a senior executive who served 14 years in Unit 8200 and a former IT leader for military intelligence, their online resumes show.

Microsoft data is housed in server farms in two massive buildings outside Tel Aviv, enclosed behind high walls topped with barbed wire. Microsoft also operates a 46,000sq m corporate campus in Herzliya, north of Tel Aviv, and another office in Gav-Yam in southern Israel, which has displayed a large Israeli flag.

The Israel defence forces have long been at the forefront of deploying AI for military use. In early 2021, it launched Gospel, an AI tool that sorts through Israel’s vast array of digitised information to suggest targets for potential strikes.

It also developed Lavender, which uses machine learning to filter out requested criteria from intelligence databases and narrow down lists of potential targets, including people.

Lavender ranks people between 0 and 100 based on how likely it is they are a militant, an intelligence officer who used the systems said. The ranking is based on intelligence, such as the person’s family tree, if someone’s father is a known militant who served time, and intercepted phone calls, he said.

Gaza is now in an uneasy ceasefire. However, recently, the Israeli government announced it would expand its AI developments across all its military branches.

Meanwhile, US tech titans keep consolidating power in Washington. Microsoft gave $1m to Trump’s inauguration fund. Google CEO Sundar Pichai got a prime seat at the president’s inauguration.

OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman met with the president on Trump’s second full day in office to talk up a joint venture investing up to $500bn for AI infrastructure.

In a new book, Palantir CEO Alexander Karp calls for the US military and its allies to work closely with Silicon Valley to design, build, and acquire AI weaponry, including “the unmanned drone swarms and robots that will dominate the coming battlefield”. He writes: “The fate of the United States, and its allies, depends on the ability of their defense and intelligence agencies to evolve, and briskly.”

After OpenAI changed its terms of use last year to allow for national security purposes, Google followed suit earlier this month with a similar change to its public ethics policy to remove language saying it would not use its AI for weapons and surveillance. Google said it is committed to responsibly developing and deploying AI “that protects people, promotes global growth, and supports national security”.

As tech companies jockey for contracts, those who lost relatives still search for answers.

“Even with all this pain, I can’t stop asking ‘why?’,” said Mahmoud Adnan Chour, the father of the three girls killed in the car in southern Lebanon, an engineer who was away at the time.

“Why did the plane choose that car — the one filled with my children’s laughter echoing from its windows?”

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates