Locked away: Thousands of 'unwanted' children failed by foundling hospitals

John Gilroy, archaeologist, outside the former Cork Foundling Hospital at Leitrim St, Cork.

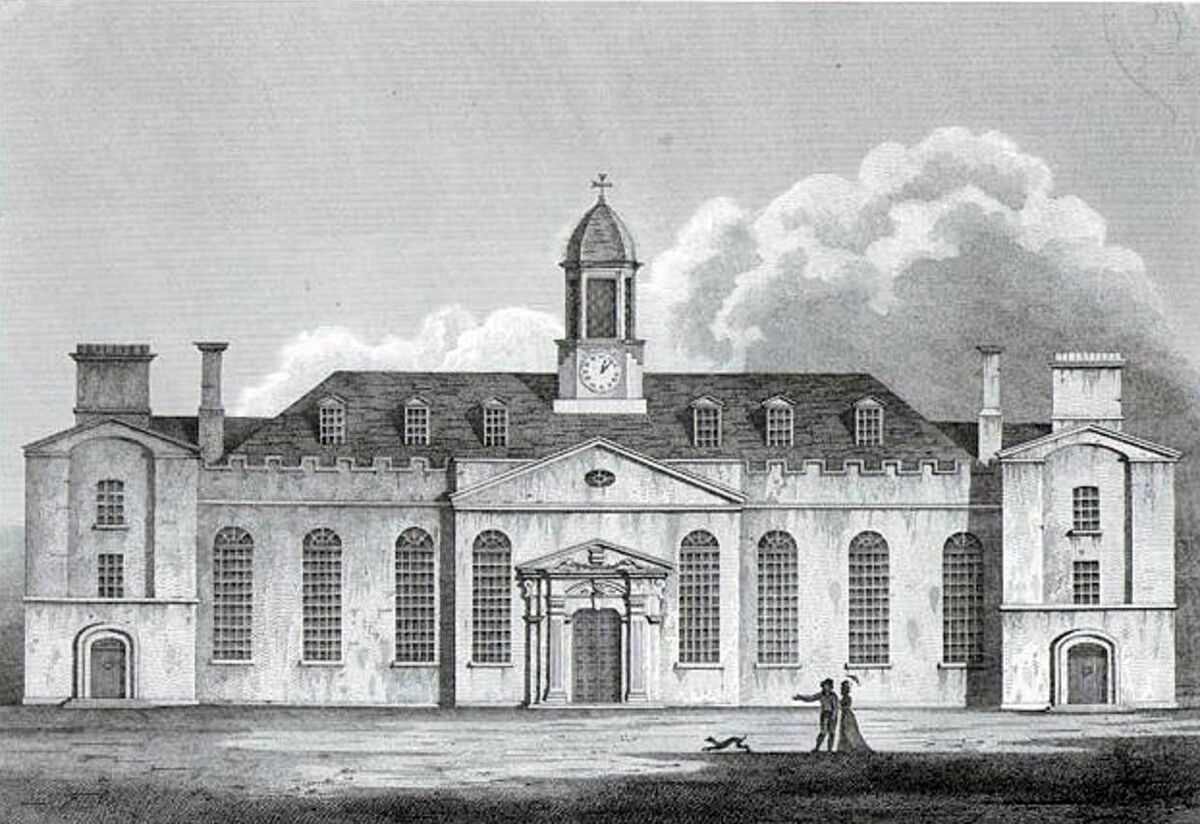

The Cork Foundling Hospital was established in 1747 on the site now occupied by Murphy’s Brewery on Leitrim St. Its construction was funded by a special tax on all coal imported into Cork. This was the source of continual complaints from the merchants of Cork, who felt that the charge was an unreasonable one.

By 1842, three interns had been ‘claimed’, 90 apprenticed and 265 had died.

The excavation uncovered an arched passageway, or cellar, which Ms Simpson identified as part of the basement of the Dublin Foundling Hospital. This is all that remains today of that hospital.

“This poor girl had travelled 100 miles on foot in order that she might herself place her child safely in the cradle and she travelled back the same weary distance. She left her child at the Foundling Hospital to be reared, she being at the time poor and unable to support her. She is now informed by letter from her brothers who were serving in the army that a remittance is to be made her to enable her to support herself and her child. She humbly begs your reverence will relieve her anxiety by giving her an order to have her child restored.”

“A rich Protestant seduced his poor Roman Catholic servant (her) and then sending her child up to the foundling hospital cradle against her will.”

“The misfortune to be seduced by a person of the name of Thomas Stackdale under a promise of marriage. The child which she bore to Stockdale was sent to a nurse, where he remained for a considerable time. The nurse demanded her wages, when the said Stockdale took the child and under an assumed name of John Johnson sent him to the foundling hospital, though very well able to keep the child”.

“Sir - There was a female child named Ann Magee sent to the foundling hospital in the month of September 1811 from the townland of Ballywooden. The father’s name is James Magee, mother’s name I forget but I think was Ann Keown. The father of the child died lately and his father and mother, who are rich and comfortable, wish to get the child back again. I do not know whether the Governors ever consent to return a child but think it would be a very happy circumstance for the child if they would accede to the old people’s wishes in this case”.

“To the Governors of the foundling hospital. The mother of a child named Arthur Wellington (admitted there on October 1, 1815) wishes him to be restored to her as she is now perfectly able to support him and most anxious to get him from the situation, she having been forced to allow him being placed there. Circumstances of a pecuniary nature obliged her to separate from his father about three months before he was born. These circumstances no longer existing, she prays and begs the Governors not to hesitate in giving him to her."

“Her child was transmitted from her on the 15th October and received into the hospital under the following circumstances. The mother Letty Spires was married to a soldier of the 611st Regiment of Foot whilst quartered here. The Regiment is gone to the West Indies and she was left behind with any provision for herself or child. She sent the child to the paternal grandfather and he sent it off to the Foundling Hospital. She is now most anxious to recover possession of her child which I trust you will have the goodness to direct that she may receive it again.”

John Gilroy, a former senator, recently graduated with a first class honours degree in Archaeology from UCC. As a former psychiatric nurse, he is interested in the history and archaeology of the numerous institutions which formed a large part of Irish society until relatively recent times.

The mental hospitals — which he is currently researching — formed one part of a society that didn’t care much for the marginalised, the poor or the unwanted.

He says the foundling hospitals, later the poorhouses, and later again Magdalene laundries, mother and baby homes, industrial schools, mental hospitals and borstals made up an institutional infrastructure which “saw Ireland as the world leader in locking away its citizens”.

Mr Gilroy pointed out that between 1728–1828, the foundling hospital served the purpose of removing unwanted infants and children from the view of Irish society.

Once inside the doors, the fate of the infants was determined by chance — healthy children sent out ‘to nurse’ and, if they survived, raised in the tradition of the established Protestant Church.

However, infants deemed ‘unhealthy’ were dispatched to the infirmary where they died in a systematic manner.

“When the scandal was exposed and the Dublin Foundling Hospital closed its doors, the systemic disposal of unwanted infants became anonymised in the overcrowded poorhouses which came into being after 1838, where the mortality rate continued at appalling levels,” he said.

“The poorhouses remained in existence until the 1920s. While it may not be valid to see a strict linear trajectory between the eighteenth century foundling hospitals, the poorhouses and the mother and baby homes, it does set a historical context to how Irish society has failed to look after the welfare of the poor, the vulnerable and the marginalised,” he added.

The foundling hospital was a phenomenon that existed across Europe and the reports of conditions within the hospitals varied.

Mr Gilroy said that in Spain, the hospitals were run by a religious order and conditions seemed relatively good.

The Barcelona hospital was praised for its “regularity, cleanliness and the manner in which it is worked is certainly wonderful".

However, in France, where there were 296 such hospitals and conditions within them were very poor; “babies (12 at a time) lying in one tray, jammed closer to each other than keys on a piano”.

The London Foundling Hospital, established as a charitable institute, maintained a much more benign environment but even so, the death rate for infants admitted in the first year ran to 40%.

In the Moscow Foundling Hospital “the size of which is truly astonishing” – of every 1,000 children admitted in 1876, 655 were alive at the end of five years.

“It seems that conditions in the Dublin Foundling Hospital, if we judge from mortality rates elsewhere, were among the worst in Europe,” Mr Gilroy said.

Wodsworth’s Report carries the example of Bridget Kearney who walked over 100 miles to leave her baby at the Dublin Foundling Hospital.

Doubtless, she was unaware of the conditions there, she must have felt that she was giving her baby the best chance.

But why would Bridget walk 100 miles when she could have availed of the services of the carrying nurse?

John Gilroy pointed out that the carrying nurse was a well-known character who would relieve the new mother of the burden of her unwanted child and take the waif to Dublin for a minimal charge.

The post of carrying nurse involved transporting infants to the Dublin Foundling Hospital from all parts of the country.

Clearly, Bridget knew that the innocently named carrying nurse was anything but innocent.

Wodsworth tells us that the admission papers of the foundling hospital state that “this child was injured in carriage (a frequent entry)”.

“In a disturbing description, the report outlines how ‘thousands of newly born infants were ‘carried’ by the professional ‘Foundling Carriers’ and were ‘carted up’ eight or ten tossed into a kish or creel (basket) from all parts of the country,” said Mr Gilroy.

“No wonder they died on the road or ‘came in dying’ and were injured and much ill-treated. Their poor little arms and legs were frequently found fractured on arrival. The dread of what these innocents suffered in transition north, east and west, on jolting springless carts or carried in a basket or sack on the backs of these old harpies — the carriers by profession must have been present in the mind of Bridget Kearney,” said Mr Gilroy.

The report continues:

The position of carrying nurse was not unique to Ireland.

Known across Europe by the grotesque epithet, ‘the Angelmaker’, the job saw children being transported often hundreds of miles to the foundling hospitals where it is estimated that the mortality rate during transit was over 90%.

In the 30 years 1796 to 1826 (this was after the scandal was exposed in 1797), 52,150 children were admitted, of whom 14,613 died in the hospital while infants.

Some 25,859 were returned as dead by nurses in the country — in all, 41,524 died.

Of 5,213 infants admitted to the infirmary part of the Dublin Foundling Hospital between 1791 and 1796, only three survived — all the rest died.