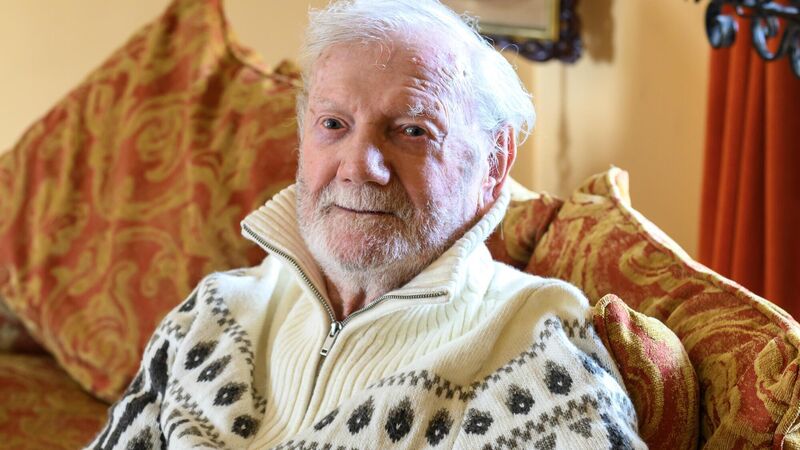

My Life: I helped sailors under attack as a child during World War ll

Martin Gordon, who came across a bombed warship with his uncle in Glasgow back in 1940

The everyday sight of a German bomber engulfed in flames and skimming my neighbours’ rooftops did little to faze me as a young boy growing up during the height of the Second World War.

If anything, war had put an end to my boredom. Even today, as a man of 94, I savour the memory of skipping school for two weeks to visit museums and marvel at diminutive warships and intricately detailed model tanks.

In the afternoons, I swapped my classroom for the cinema, enjoying lessons instead from Hollywood stars such as Cary Grant and Humphrey Bogart.

I was having the time of my life until I arrived home one afternoon and found the school inspector waiting for me.

Still, for me at least, it was an exciting time to be a child in Glasgow. With bombs going off at regular intervals, my world exuded energy and drama.

I remember the resilience of my family, most notably my grandfather, who had fought in the First World War. Even during air raid alerts, he insisted on staying put.

“I fought them in the last war,” he would say. “I won’t be leaving my bed for any bloody Germans.”

War had become the most natural thing in the world to us youngsters. I had no fear but I am convinced it was my faith in God that kept me strong.

One of the most exciting days for me came in 1940 when I helped two navy sailors who had dived to safety from their bomb-ravaged warship — the HMS Sussex.

The county-class heavy cruiser associated with the Royal Navy had been commissioned a year before I spotted the sky ablaze while staying in my uncle Jimmy’s apartment. The windows shook but none broke.

Never one to shy away from danger, Jimmy suggested that we go and find out the cause of the explosion.

So there we were walking down Govan Rd, right past Harland & Wolff — the same shipyard that built the Titanic — when we saw the sky lit up.

We reached the steps of what we referred to as “the wee ferry”. The water was dotted with sailors, two of whom were swimming towards us.

From what I gather, a German bomb had been dropped down through the funnel before exploding in the engine room. The crew had been ordered to abandon ship, leading to utter chaos.

Because it was loaded with ammunition to go on convoy duty to Russia, the captain decided to scuttle the ship.

This is the technical term for deliberately sinking a vessel by opening up holes in the hull or seacocks to flood the ship. It is typically used as a last resort to evade capture by an enemy.

In the case of the HMS Sussex, it was to prevent a catastrophic explosion. The whole district was in danger of being blown up, including a children’s hospital on the hill above us.

We watched as the ship lay on its side and the sailors grew closer. Fortunately, we were just in time to help them out of the water.

I mustered up Herculean strength to help my uncle haul them both to safety. The shock was evident from the men’s empty stares.

Their personalities lay trapped in the shells that were their exhausted bodies. Any attempt at further interaction was avoided as we led them back to Jimmy’s apartment.

Away from the noise and frenzy, we sat in silence with the sailors for some time. Jimmy served up towels for them to dry off.

They were given blankets to keep warm while their uniforms dried near the gas fire.

Jimmy’s wife, Lottie, put the kettle on to make them tea. When the kettle came to the boil, it let out a whistling noise. Still in shock, the sailors dived for cover on the floor, believing they were in the midst of another bomb.

Neither man had the energy for more than sipping tea and nibbling at bread and marmalade.

My uncle and his wife’s comforts were little consolation to them as they struggled to come to terms with the trauma.

Morning eventually cast its hopeful light, and the sailors left in uniforms, still slightly damp. They reported to the nearest police station before returning to their headquarters.

Life continued as normal after that. I became a voracious reader and studied the war charts in the papers every morning before school. I was still too young to fully grasp the trauma and heartbreak that war had already left in its wake.

Sometimes we’d hear of neighbours being killed in the war. I remember one woman’s tear-soaked expression as she stood before her window.

The saddest moment of all came when Clydebank as a district was almost totally destroyed.

One man asked an air raid warden the next morning how many people had died: “I heard the death count was 2,500 — is that true?”

The air raid warden’s reply said it all: “It depends on which street you are talking about.”