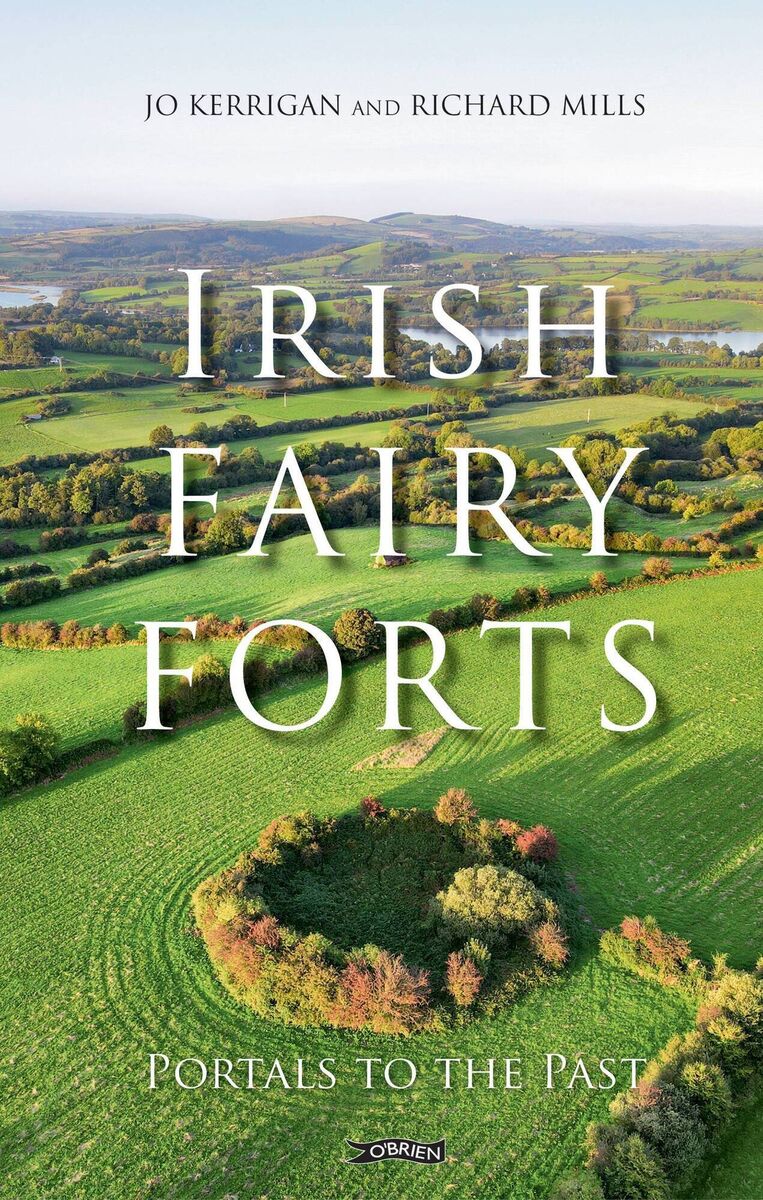

Fairy forts — so many still here and still relevant today

Rath Mór ringfort near Rathmore. Pictures: Richard Mills

A few will have two or even three protective ditches and banks surrounding the central circle, but often these have been eroded by time or filled in by usage of the surrounding fields. The enclosed space may be no wider than 15m or, rarely, may be as extensive as 40m. (Incidentally, in the ancient Brehon laws, the dimensions dictated for the residence of a tribal king, which would certainly have been a caiseal or dún, was c.140 feet, or 42.56 metres.)

- Lissarda (the high fort)

- Lisdoonvarna (the lios at the fort of the gap, a nice example of lios and dún combined in the same place name)

- Lisduff

- Lismore

- Lios napuca

- Lisnakea in Fermanagh means ‘the fort of the sceach or whitethorn tree’.

- Rathmore (the large fort), between Millstreet and Killarney. The town and railway station hug the main road, but south of the conurbation in a quiet field lies the original Ráth Mór that gave the place its name. Every time the train passes Charleville in County Cork, the conductor announces in Irish ‘An Ráth’, which is its proper name, commemorating the ancient ringfort.

- Rathdangan

- Rathpeacon

- Ratheenduff (the little black fort)

- Raheenroe or Raithin ruadh (the little red fort)

The huts or houses within a ráth or lios would have been built simply of posts with interlaced rods and coverings of reeds or straw, while in a grander dún or caiseal stone would have been used. There would also have been shelters within the central space for livestock. Unsurprisingly, very little evidence remains of these original layouts, but archaeological excavation has yielded enough information to enable several excellent reconstructions to be built — for example at Lough Gur in Limerick and the Irish National Heritage Park in Wexford.

Arguments also continue in archaeological circles as to how far back these structures date, but while some are content to say “medieval or thereabouts”, the current trend is to move at least some of them well back into prehistory. It is, in fact, pretty difficult to date something made of timeless earth and stones. Quite often, an arbitrary century is allocated based on what has been found in an excavation. If artefacts are recovered, and these can be dated fairly accurately, then the structure itself is usually given the same date — although that is hardly satisfactory, given that such places might well have been occupied for many generations.

- by Jo Kerrigan and Richard Mills (The O'Brien Press) is out now.