Wrecked ship and treasure lost off Irish coast for nearly 400 years

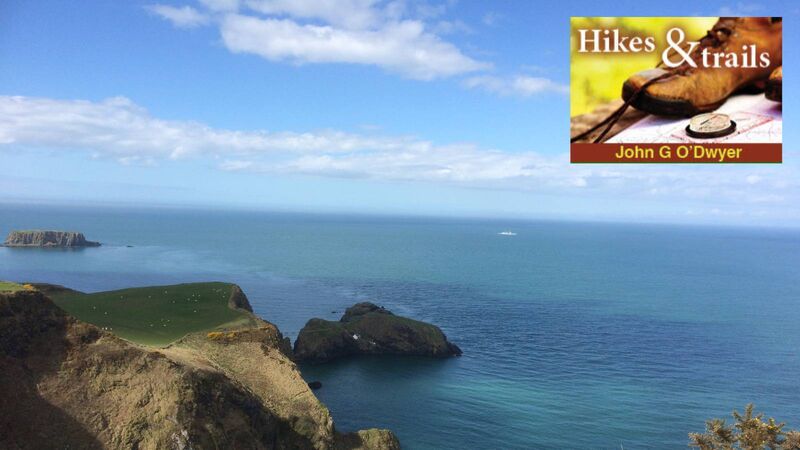

The deceptively serene Causeway Coast. Picture: John G O'Dwyer

On July 29, 1588, having been delayed by bad weather, the mighty Spanish Armada set sail, full of confidence, from La Coruña. England had long been a thorn in the side of Catholic Spain and the objective of the Armada was to conquer the country and remove the Protestant Elizabeth I, from the throne.

Among the departing ships was La Girona: a large, heavily armed vessel powered by sail and oar that was primarily designed for use in calmer Mediterranean and tropical waters.

On their first encounter with the enemy, the Spaniards faced a nasty surprise; they discovered that bulky ships such as La Girona were no match for the lighter, more nimble British vessels.

Soon the Armada had been scattered and an invasion of England was no longer possible. For each ship’s captain, the sole objective was now returning safely to Spain.

Forced to sail around the north of Scotland, the Armada was battered by fierce Atlantic gales, for which the great lumbering galleons were poorly designed to cope.

Eventually, the storms damaged the rudder of the Girona and she was forced to put in for repairs to Killybegs in Donegal. Here, McSweeney, the local Gaelic chieftain, who was no friend of the English, assisted with repair work.

Meanwhile, other ships of the Armada were being battered to matchwood along Ireland’s unforgiving west coast. About 800 Spanish survivors from 2 of these shipwrecks made their way on foot to Killybegs seeking passage to Spain and were taken aboard the Girona.

Now carrying 1,300 men on a vessel designed for fewer than 500, the captain decided to make the short voyage to Scotland, which was then, unlike Ireland, an independent nation. This would allow recuperation and reprovisioning before undertaking the arduous passage to Spain.

But they never made it!

Having rounded Malin Head, a fierce northerly gale hit the Girona and her rudder failed again. No longer able to move away from the dangerous Irish coastline by tacking (zig-zagging) into the wind, the only hope now was that the oarsmen could drive her forward at a speed that would allow her round Fair Head where she could run south before the wind. This would save the ship from being swept onto Antrim’s rocky coastline.

It was a race against time, but it soon became obvious that the exhausted rowers could not achieve this speed. Helpless as a drifting petal, the Girona was blown towards great cliffs. At this stage, it must have been blindingly obvious to all that the wooden ship was doomed to splinter on the rocks and most of those on board were about to succumb on a lonesome, inhospitable shoreline.

Today in 1588 one of the Spanish Armada's most prestigious ships, Girona, overloaded with weakened survivors of previous wrecks, smashed into rocks here off the Antrim coast.

— Dan Snow (@thehistoryguy) October 26, 2020

Her treasures in the @UlsterMuseum are breathtaking. pic.twitter.com/aZGuI25T44

Striking the rocks off Lacada Point near the Giant’s Causeway around midnight on October 26, the Girona quickly disintegrated, with all on board perishing except for about nine survivors. Fortunate to have come ashore where the friendly McDonald clan held sway, they were given safe passage to Scotland.

This gold tooth and ear-pick in the form of a dolphin from the Girona in the Armada Shipwreck may have saved you a trip to the doctor or dentist once upon a time. The long snout forms the toothpick, the flattened tail the ear-pick – while the dolphin's eye watches with distaste! pic.twitter.com/aWt4R14T57

— Ulster Museum (@UlsterMuseum) April 14, 2020

After this tragedy, Lacada Point became known locally as Port na Spanaigh but for many generations, the Girona lay hidden beneath the ocean with no one able to pinpoint its exact location. Almost forgotten, the sinking was recalled again in 1967 when a team of Belgian divers came to Port Na Spainaigh led by Robert Sténuit, who was attracted by tales of the huge treasure onboard the Spanish ship.

After many fruitless attempts, the divers finally discovered the wreck site. The timbers had long disappeared, but the murky ocean floor was littered with an enormous hoard of Armada treasures, including gold crosses, brooches and coins, silver candlesticks, gilded tableware and cannons. These treasures now rest in the Ulster Museum and are well worth a visit when in Belfast.

To explore Port na Spanaigh, start from the Causeway Visitor Centre on the North Antrim Coast. After 20 minutes going downhill, you gain the Giant’s Causeway and find yourself in the company of 37,000 hexagonal columns that were created by rapidly cooling lava 60 million years ago as the basalt fractured like drying mud.

Then, it is on through a gap in the rocks to a captivating little bay called Port Noffer. Here, a large rock marooned on the stony beach has been dubbed the Giant’s Boot, while the surrounding columns have been christened the Organ. Swinging right, you ascend a steep path named the Shepherd’s Steps. Then it is left along the clifftop above the remarkable amphitheatre of Port Reostan to reach the Chimney Tops viewpoint. Beneath, lies the poignant but beautiful Port na Spaniagh where the Spanish went to a watery grave. Return along the clifftop, bypassing the Shepherd’s Steps and continuing straight ahead to the Visitor Centre after a memorable 90-minute outing.

- A fuller account of walking on the Causeway Coast is contained in John G O’Dwyer’s book, , available from bookshops and currachbooks.com