From France to Slievenamon and then Dublin Castle — the story of Ireland's tricolour flag

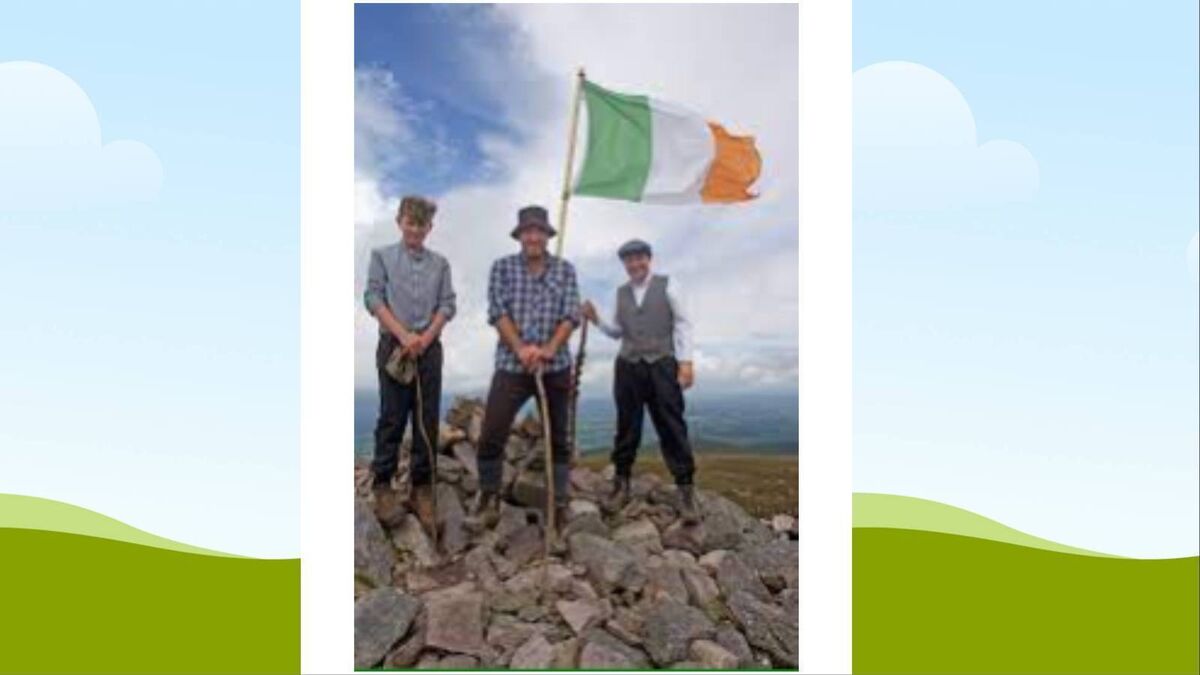

Walkers approach the summit cairn on Slievenamon. Picture: John G O'Dwyer

In contrast to the bulkier and more angular Comeragh and Galtee mountains, this is an isolated eminence with graceful flowing shoulders that seem destined to gather legends. Overlooking the Tipperary countryside like a benevolent grandmother, Slievenamon remains the quintessential Tipperary mountain — a unifying backdrop for South Tipp folk as they go about their daily business.

Most hillwalkers follow a stony track from above Kilcash village that trundles over a low rise and then reaches the flattened top after a walk of about an hour. Immediately noticeable is a huge burial cairn, reputed to contain the sequestered entrance to the Celtic Underworld for Ireland’s fairy folk.

The full #BeaverMoon rising over Sliabh na mBan, Co. Tipperary, Ireland. Planned with @photopills #KeepDiscovering #StormHour#Slievenamon pic.twitter.com/05JK54u3yW

— Olly Griffin (@OllyGriffin) November 27, 2023

A depression among these rocks is known locally as Fionn MacCumhaill’s seat. A remarkably durable myth holds that it was from this perch the legendary Irish mythical hero watched an abundance of candidates for his hand in marriage race to the summit. Legend has it that he cheated and helped his favourite — Gráinne — to prevail.

Having tasted the Salmon of Knowledge, Fionn was reputedly the wisest man in the world — but not wise enough, it seems, to give Gráinne a wide berth. He failed to foresee that she would, unimpressed by his devotion, elope from the wedding banquet with the much younger Fianna warrior Diarmuid, who is reputed to have carried an irresistible 'love spot' on his forehead. The couple were then chased across Ireland by a vengeful Fionn, which provided the material for the mythical stage and film melodrama of Diarmuid and Gráinne.

Not a myth is the fact that it was here Waterford man, Thomas Francis Meagher of the Young Ireland movement, came in July 1848 to preach the doctrine of rebellion. From a relatively privileged background, he initially became involved in the Repeal Association, which aimed to end the parliamentary union between Britain and Ireland. Growing impatient with Daniel O’Connell’s pacifist style of politics, he gained the moniker 'Meagher of the Sword' for his incendiary style of oratory that espoused violence as a means to political ends.

Early in 1848, Meagher journeyed to France to study the recent revolution which had ousted the French King Louis Philippe, and installed a republican government. Here, he was presented with an Irish flag based on the revolutionary French tricolour. It consisted of green, white, and orange bars — with the white symbolising a peaceful union between Ireland’s green (nationalist tradition) and orange (loyalist tradition). Flown for the first time in Waterford on March 1848, it was later unfurled for the Slievenamon gathering.

Now with a steadfast commitment to overthrowing British rule in Ireland Meagher, along with fellow Young Irelander Michael Doheny, used the great symbolism of Slievenamon’s summit to give rousing speeches to an estimated 50,000 people that contained an implied threat to British authority in Ireland.

According to the advance publicity, the objective of the meeting was to demonstrate “determination to obtain Irish independence by constitutional means if possible". The immediate response by the authorities was the imposition of martial law.

Then followed the Young Irelanders’ contribution to the 1848 year of revolutions in Europe, which has since been dubbed the Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch. Following a stand-off with police at a widow’s house near Ballingarry, County Tipperary, which was referred to by later revolutionaries as the 1848 Young Ireland Rebellion, the rebels fled.

Meagher, who was not present at Ballingarry, was later arrested for sedition and sentenced to death. Conscious of the need not to create martyrs, the British government wisely commuted his sentence and transported him, along with the other leaders of the rebellion, to Tasmania.

In 1852, he escaped and made his way to New York, where the highly erudite Meagher qualified as a lawyer. Rising to the rank of Brigadier-General in the US Army during the American Civil War, he led the famous Irish Brigade. After the war, he was appointed acting governor of the Montana Territory. Here, he developed the first constitution for the new State, before drowning when falling overboard from a steamboat boat on the Missouri River in what some considered suspicious circumstances.

Following the defeat of the Young Ireland Rebellion, the tricolour fell into disuse and seemed a mere postscript to history. It was, however, unfurled again over the GPO during the 1916 Rising and immediately became a powerful symbol of Irish nationalism. In January 1922, it was raised officially for the first time when Dublin Castle was handed over to Michael Collins by the withdrawing British authorities in Ireland.

It then became a contested symbol in the Irish Civil War, with both sides claiming it, before being formally confirmed as Ireland's national flag by the 1937 constitution. And more recently, it flew once again over Slievenamon’s summit, in July of this year, to mark the 175th anniversary of Meagher’s momentous, 1848 speech.

- A fuller story of historic happenings on Slievnamon is contained in John G O’Dwyer’s book, , available at currachbooks.com