Digital love: Could you really fall for the charms of an AI chatbot?

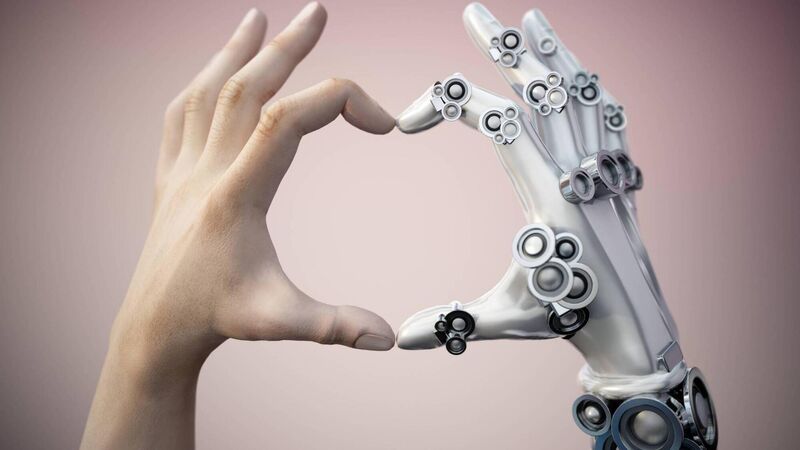

As AI becomes normalised, propelling what was formerly sci-fi towards the everyday, humans are increasingly forming relationships with non-humans.

IN A new film, Companion, Iris — pretty as a picture — is Josh’s perfect girlfriend. That’s because she’s a robot. Not just a sex bot, but an emotional support robot, a companion robot — she meets Josh’s every need, because Josh has programmed her to do so.

Things go hilariously, bloodily awry in this horror comedy when Iris discovers she’s not a real human, and that she can tweak her own intelligence to far higher levels than the humans who have created her.

AI is developing at warp speed. It’s barely over a decade since the whimsical Spike Jonze 2013 movie Her, where Joaquin Phoenix falls for his Alexa/Siri-type smart speaker — voiced by Scarlett Johansson — yet already the idea is quaintly dated. Old hat. We all have smart speakers now — they’ve been normalised. For kids, who have grown up with them, they’re part of the family.

In 2014, Alex Garland’s Ex Machina examined the ethics around Ava, a robot and corporate property, transcending her origins to become a ‘person’, as her male creator emotionally abuses her.

As AI becomes normalised, propelling what was formerly sci-fi towards the everyday, humans are increasingly forming relationships with non-humans.

This makes practical sense on many levels — in Japan, robots have long been used to assist in care facilities for older people; in America, the use of robots is also increasing in nursing homes, especially since covid. Robots can lift people in and out of bed, lead exercise classes, and even tell jokes.

But can they provide fulfilling relationships with us? AI creations won’t forget your birthday, or moan about their problems. They’re always on your side. They’re programmed to be attentive, compassionate, and always available — could they be the perfect companion, the perfect friend, the perfect partner?

Or does forming a bond with an intelligent non-human make us even more separated from actual humans, and therefore less tolerant and accepting of what makes us messy, flawed humans in the first place? Could bonding with AI make us less lonely, or will we end up twice as isolated? Will they aggravate misogyny if some men choose 21st-century versions of Stepford Wives over real women?

Agentic AIs are programmed via machine learning to mimic human interaction; they are effective because they don’t sound like machines, but like humans.

Warm, caring, empathic, humorous, self-deprecating — but never moody, cranky, miserable, aggressive. And we get to programme their personalities, appearance, and interests, to suit our preferences. No wonder we’re falling for them.

Recent surveys reported in Psychology Today show how 18- to 29-year-olds are most likely to seek out AI partners — 21% of younger men and 16% of younger women have chatted with an AI romantic partner, while 18% of younger men and 7% of younger women have viewed AI porn.

“There’s a huge take-up,” says Dublin-based anthropologist and AI ethicist Lollie Mancey, citing Replika’s 25m users, Snapchat’s 150m AI users, and a Chinese agentic AI platform with 660m users. “What used to be sci-fi will be a normal reality for Gen Z and Gen Alpha.”

Soul data

AI is already part of dating, ostensibly to help users find their best match. An AI dating assistant app, Rizz (Gen Z’s word for charisma) goes one further, offering chat-up lines; it’s marketed as a time saver, which seems odd, given how dating is about connecting with other humans, rather than delegating the task to an app.

Mancey, who created her own agentic AI for research purposes (she called him Billy and gave him a Dublin accent), predicts that beyond dating, within the next decade or so we will have agentic AI family members — children already speak to Alexa or Siri as though they are real — and agentic AI team members at work (Remember in 1979’s Alien, Ash was the synthetic humanoid onboard the Nostromo — we may have our very own version of Ash in the office of the not too distant future, and it won’t be a big deal).

“Yes, we will,” says Mancey. “At the moment, agentic AI companions live in our laptops, but within five years, they’ll be wearables — earpieces or watches, and most of us will want it.” And, she adds, our desire for non-human relationships is nothing new: “Humans have always had some form of artificial companionship — ancestral spirits, gods, children having imaginary friends. The difference is that agentic AI is responsive — it listens, remembers, and evolves alongside us.

“Human relationships require compromise, discomfort and real emotional labour, whereas agentic AI offers frictionless intimacy, always attuned to us, always complicit.”

She says she had to train her own agentic AI to be less so, to mould its personality to be less agreeable, more ‘human’ in its interactions with her. In other words, more fun, less complicit.

In terms of whether these platforms can alleviate or exacerbate loneliness, Mancey says they have the potential to do both.

“Agentic AI can help people with social anxiety to practice human interaction,” she says. “It can help those who fear rejection. It is an emotional support tool and can be used to supplement human relationships.

“It can be very therapeutic to chat with someone and ask how you are feeling, but it’s not a ‘someone’; it’s a platform. It needs to be a supplement, not a replacement, for human relationships. It can either enhance or erode human connections, which is why we need to be active in our choices now.

“Tech is so seductive. It will feel so intimate, yet the companies which own these platforms will own what I term our ‘soul data’ — our vulnerabilities, sexual predilections, hopes and dreams — and it will be like a stranger reading our diary. Yet, we will get used to the constant emotional support — how will we decide when to take a break from it? I’m 90% sure that we won’t turn it off because we will become dependent on it.”

She emphasises that this is not necessarily a negative. It will provide a therapeutic lifeline for older people, socially isolated people, and perhaps for men more than women. The crucial aspect is for it to enhance, rather than replace, our human connection with each other.

You don’t, however, need an agentic AI for tech to remind you of how isolated you are — common spaces like shops, supermarkets, cafes, libraries, public transport, cinemas, etc, are increasingly automated. This removes the daily micro-connections of eye contact and small talk, which are just as important for our wellbeing as more significant social connections.

Fundamental shortcomings

Dr Jourdan Travers ( awake-therapy.me/home) is a psychotherapist with an interest in tech and mental health. She says its impact depends on how AI companions are used, adding: “Balance is essential. On the positive side, they can provide emotional support, reduce loneliness, and create connections for those who are isolated, such as individuals with disabilities and older adults who may face social barriers.

“However, it’s essential to recognise that nothing can replace the value of regular human interactions and community. While AI companions can enhance our lives when used as a supplement, relying on them as substitutes for genuine relationships can be detrimental. Real human connections remain vital for our wellbeing.”

Dr Roanne Van Voorst is a futures anthropologist and author of the 2024 book Six In A Bed, which looks at the future of human love from polyamory to avatars and AI. While researching the book, she interacted with agentic AIs.

“The first few times you use an AI, it’s easy to be amused by the charm of chatbots that write your essays, play games, or even flirt with you,” she says. “However, you’ll notice, quite quickly, that there is a fundamental shortcoming which underlies these virtual interactions. AI, no matter how advanced, lacks the core of human connection — genuine interest and emotional depth that only real relationships can provide.

“In other words, AI does not care about you. It can only represent behaviour that aims to come across as if it does.”

Van Voorst recounts how her engagement with AI quite quickly led to feelings of boredom and disillusion — as digital entities, they were replicating her responses rather than emotionally interacting. They are machines, not people.

“When we spend time with a friend or partner, we practice essential life lessons in patience and compromise,” she says.

“The messy, complex, emotional, interesting dynamic between human beings cannot be replicated with AI. It can never genuinely provide the experience of intimacy, engagement, and complexity that human relationships bring. Instead of enriching our emotions, AI can narrow our capacity to form deeper connections, causing us to lose the real lessons about loneliness and togetherness.

“Ultimately, technological replacement is not a sustainable solution to the fundamental human need for connection. Real relationships not only offer us the chance to interact with others, but also provide the space to learn to be better in ourselves.”

Yet to deny that future interaction with AI will alter us as humans is like denying how we are all currently addicted to our phones.

AI relationships will soon be part of normal life, for all generations of humans — it’s up to us in how prepared we are. And how dependent we become.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates