Culture That Made Me: Robert Sheehan picks eight of his touchstone influences

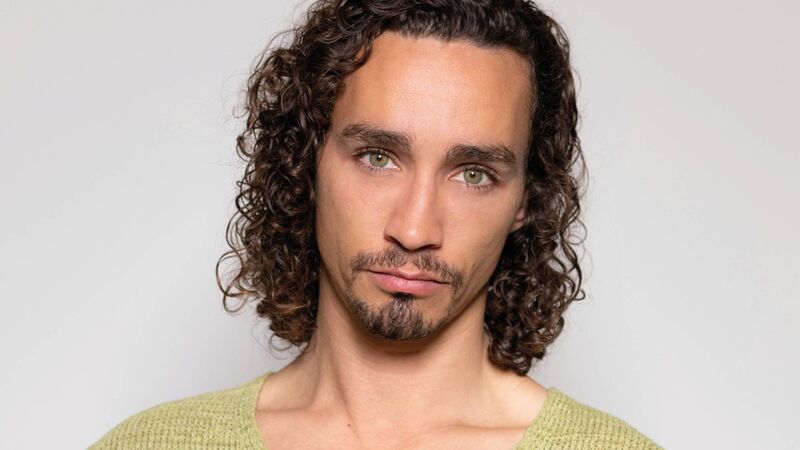

Robert Sheehan, actor and author Picture: DWGH Photography

Robert Sheehan, 33, grew up in Portlaoise, Co Laois. He has starred in shows such as Misfits, Love/Hate and Netflix superhero series The Umbrella Academy. His short story collection Disappearing Act was recently published by Gill Books.

In our house growing up, we always had lots of VHS tapes of Friends lying around. It was like brain sugar. My sister in particular was devoted to Friends. She had six or seven tapes, all saying, “Do not tape over on pain of death”. My favourite was probably Chandler Bing, Matthew Perry’s character. He was incredibly witty. Looking back, and knowing a bit more about American television now, Chandler was like a more attractive George Costanza from Seinfeld – a neurotic with the heat turned down. His delivery was the funniest, that’s what it came down to, and there was more tragedy to him.

The Simpsons is knock-out funny. It has well-written characters in a domestic setting, a completely dysfunctional family, which makes you feel better about your own dysfunctional family. There’s an episode I watched probably more than any: Marge tries to keep it from Homer that there's a chili-cooking festival happening in Springfield. She cuts articles out of the newspaper. He finds all these clues. He gets down there. Chief Wiggum has this rare chili. Nobody is willing to eat it. Homer eats the whole thing down. Then he has a mad sort of acid trip. His spirit animal is a fox with Johnny Cash’s voice who guides him around. It has such exciting writing. You never know what they’ll throw at you.

I liked anarchic stuff when I was a kid like, say, Ace Ventura. It was such a stimulating performance by Jim Carrey. He went to such a bizarre, surreal place. I'd never really seen a film actor doing that. Particularly Ace Ventura, which was great because the director Tom Shadyac edited him like as if he was in an old Spencer Tracey noir movie, investigating the kidnapping of this dolphin. Everybody treating him like he's a fully-fledged human being, and not a complete nutter. That appealed to me.

I remember saying to my mother when I was young, about 10: “I'd like to be on television.” She said, “Oh, we’ll enrol you in it.” It was said in support, without knowledge about how things worked, of how people ended up on television. When I was 12, I did a play in my primary school, which included improv and audience participation. I caught the bug after that – performing to audiences on stage absolutely knocked me for six. It’s stimulating for a kid, the cheering, the clapping. The waves of energy you're getting from an audience is addictive, the approval you’re receiving at that hour of your life. You’re thinking: “This is great – getting accepted to an extreme degree.” It was an important moment.

You can't take your eyes off Barry Keoghan when he's on screen. He's got an edge. He can be dangerous. For example, in The Green Knight he plays this scavenger who’s being all nicey-nice. He seemed to come out of the box fully aware. He’s good at not overacting. He never does too much. He's got enough self-assurance that he knows exactly how much to do, how much to portray, how much to act. A lot of more experienced actors do too much acting.

The last time I was on stage in a significant way was with the director Trevor Nunn. Early in rehearsals, I’d been practicing the opening speech by Richard III, murmuring to myself at home, before doing it in front of a big table, with Trevor sat behind it. Part of why he is so wonderful is because he is incredibly positive and encouraging. He has a knack for taking you in very, very close, almost whispering to you, making you feel like you’re the only person in the room. He’s really sweet and kind, almost childlike. All the fear and nervousness I was feeling, practicing in this gigantic room in front of him was a pain barrier I had to get through. He gently led by my hand, and helped me slay the dragon of my own anxiety. I was out my depth. I had never done Shakespeare before. He’s a powerful director.

When I was a kid, I loved reading Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. I was glued to the books. The world building in them is incredible. It's essentially a world like ours, but it has these wonderfully told, magical elements. Everybody has a sort of spirit animal that follows them around and is their companion. Ultimately, it shifts and changes shape until that person reaches a level of maturity. It has all these beautifully thought-out ideas. They’re very spiritual books.

An aspect of Samuel Beckett, which seems to be one of the core grains at the centre of his writing, is a resentment for having been born. He was Buddhist in the way he understood that life – having a body, being in the material world – is suffering. He takes away a lot of a human’s autonomy in his plays. He takes away movement. He takes away their bodies. In Not I, the character is just a disembodied mouth. In Endgame, one character can’t stand up; one character can’t sit down. The other two are in dustbins so they can’t move. Everybody is barely alive. They're resentful of their mortal lives, but they’re clinging on to them at the same time. That strange paradox he somehow makes funny.