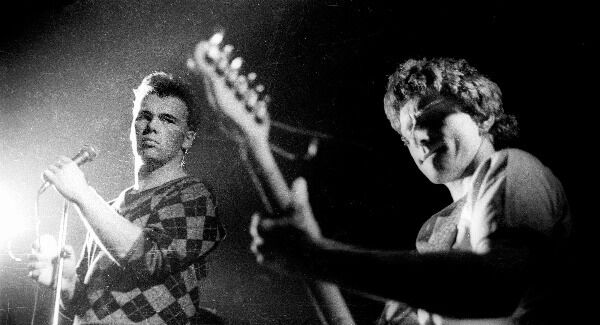

Cork band Microdisney turning back the clock

As Cork legends Microdisney re-form to play their classic album in Dublin and London, chats to the band and some of their early champions

One afternoon early in 1985 two Irish exiles found themselves in the departure lounge of a Polish airport, cradling a year’s supply of cherry vodka. Cathal Coughlan and Sean O’Hagan had taken their band, Microdisney, on an unlikely tour of the former Soviet Bloc, highlights of which included ghosting down chillingly deserted East German motorways and, passing a road accident in Poland, seeing their first dead bodies.

They were on the road honing material for their second full length album, The Clock Comes Down The Stairs. And if 1980s Cork wasn’t quite as repressed as Communist Central Europe, the duo may have caught, in the hopelessness and simmering resentment of the locals, a reflection of what they had felt living in theocratic Ireland.

“The audiences had been a bizarre mix of music fans and mams, dads, uncles and kids,” recalls O’Hagan, as Microdisney prepare to reprise their landmark LP in Dublin this weekend.

Leaving Poland you had to get rid of your zloty. You had to buy something. But there was nothing to buy. I remember leaving Poland with lots of cherry vodka, candles and a rug. It was like something from a film.

Microdisney’s story had a cinematic quality too — Withnail and I, with a splash of the Filth and the Fury perhaps. With The Clock Comes Down The Stairs, released several months after their Polish odyssey, moreover, they synthesised a kaleidoscope of influences that included Scott Walker, Flann O’Brien, the Beach Boys and Velvet Underground, into something approaching a masterpiece.

“That album never gets old,” says Tom Dunne, lead singer of Microdisney’s Dublin contemporaries Something Happens who, as a radio presenter, has been a tireless cheerleader for Coughlan and O’Hagan and, in particular that classic record.

“As a document of ’80s Irish youth it is unsurpassed,” says Dunne, whose championing of the album was one of the things that pushed the band to reform.

LONDON IRISH

Garreth Ryan agrees with Dunne’s appraisal. A Dubliner who has worked in the UK music industry since the 1980s, Ryan and signed Microdisney, to his London-imprint Kabuki Records when they first moved from Cork to Britain.

“It wasn’t really until I heard tracks from Clock played by Tom Dunne or John Creedon or elsewhere on Irish radio over the last decade or so that I realised just how phenomenally well it has worn,” says Ryan.

The Clock Comes Down The Stairs also succeeds as a chronicling of being Irish and a bit down and out in 1980s London. Coughlan and O’Hagan may have been two of the great Irish songwriters of their generation but they still found themselves working on building sites and, in one surreal occasion, drafted in to re-sleeve Smiths records for their label, Rough Trade, after Terrence Stamp refused to allow his likeness be used on the cover of ‘What Difference Does It Make?’.

“On the whole, British people are decent and truth be told, they hold the Irish in high regard,” recalls Ryan.

With the times that were in it, there was undoubtedly some hostility to the Irish from some quarters, though it was rarer in London. It must be said that nearly every instance of anti-Irish sentiment I encountered during the 1980s came from the Metropolitan Police.

“One of the more surprising things as you get acclimatised to living in the UK was just how little the English, in particular, know about Ireland. So you let them know a little bit more and they’re well able for it. I think maybe Microdisney’s growing fanbase in the UK had an appetite for an ‘outsider’s perspective’ on their world.”

“The UK was pivotal,” recalls Tom Dunne. “It was the centre of the European music scene and had a huge effect on US tastes. Each Irish band was judged on its merits. There was still a suspicion that we weren’t quite as sophisticated as UK bands. There was also a bit of suspicion that we were show-bands, it was in our DNA. We also weren’t part of the London clique. It was difficult to break into, and eye opening.”

“A lot of Irish bands who came to London ended up living on the edges of the city, like New Cross, Peckham, Finsbury Park, Wood Green, Hackney,” says Stuart Bailie, a Belfast journalist who wrote for publications such as the NME and Melody Maker (Trouble Songs, his chronicling of the relationship between music and conflict in the North, has just been published).

“Places that weren’t always served by the tube line. A lot of night bus rides and a sense of dislocation. Former members of the Undertones were working on building sites. Other musicians were couriers or labourers. It was tiring to get beyond this.”

For Sean O’Hagan, the band’s move to the UK was a return to the country he had gone to school in.

“Cathal had a very objective view of what we were landing in,” he remembers.

We both observed the Falklands War, the change in the music scene, the emergence of fashion as an add-on to music, the New Romantic culture. Cathal had a great objectivity. We were both also really young, so there was also a slight fearless, almost a naive quality.

SOCIAL THEMES

The Clock Comes Down The Stairs came together against the backdrop of Thatcherism and social unrest in the UK. There are, the pair acknowledge, uncanny parallels as they prepare to perform it once again.

“There is an aspect of [the record] that does seem rather uncanny and [thematically] might have been uncalled for a couple of years go,” says Coughlan. “I’m particularly thinking of the song ‘Past’ [a skewering of the “Little England” worldview].

It is a mindset which is by no means universal in Britain but is pronounced all the same. Until about 2010 people thought that stuff had completely had its day. Ever since, it’s been one way traffic — leading to the 2016 referendum and the mob rule we are seeing on the back of that.

The album was released on Rough Trade, then one of the Britain’s foremost independent labels.That was both a blessing and a curse. The imprimatur of Rough Trade and its founder Geoff Travis carried huge weight. But it was also home to The Smiths, and there was little doubt as to where its priority lay.

“As I recall, Microdisney arrived at Rough Trade at roughly the same time as The Smiths,” says Garreth Ryan. “Rough Trade very much needed the Smiths to succeed at the time, in fact the whole sector needed both the Smiths and Rough Trade to thrive. It was nice for a while to know that there was an active, growing audience listening to and buying literate, new popular music that could cross over to Joe Public.”

“Rough Trade was an endorsement for any band,” says Stuart Bailie. “Stiff Little Fingers was their first success in 1979, so there was an Irish connection since then.”

Microdisney were subject to quiet praise and a bit of bafflement. Great, obtuse lyrics, peculiar music. “They tended to be written about in pretentious features, something of a fashion in the post-punk, post-modern era, led by Paul Morley and Ian Penman at the NME. I don’t think many people assumed they were going to be stars, like The Smiths, the breakthrough Rough Trade band.

Microdisney seems like a band that was reasonably content to be on the fringes of things. Artistic freedom but modest sales and a scrounge existence.

EARLY BOND

O’Hagan, originally from Luton, had met Coughlan at a party in Cork, at which they bonded over their shared musical tastes and were soon building a reputation by supporting visiting acts such as Depeche Mode and U2. They bristle slightly at the suggestion of a yin-yang dynamic in their partnership.

Nonetheless, it’s clear that Coughlan, who wrote the lyrics, brought an acerbic quality, offset by O’Hagan’s love of classic pop, in particular the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds.

Microdisney’s first album, 1984’s Everybody Is Fantastic, hadn’t created much of a splash — barely a ripple even. Having been regarded as the next big thing in Cork and Dublin (where Hot Press writer Bill Graham was a passionate supporter) it was disconcerting to be faced, as many Irish bands would be, with yawning indifference in London.

PEEL SESSIONS

One bright spot was the backing of BBC DJ John Peel, who bestowed upon Microdisney the ultimate honour of inviting them to record several greatly-vaunted Peel Sessions. It was the ideal preparation for The Clock Comes Down The Stairs, ultimately largely assembled in the Ladbrook Grove flat of their producer Jamie Lane (with drums and auxiliary instrumentation applied at a studio in Shoreditch).

“Those Peel sessions allowed us to hear the songs and do something more expansive than what was going to happen in anyone’s living room,” says Coughlan.

“That was a godsend,” adds O’Hagan. “It concentrated our minds and gave us a structure, something to aim towards. By the time [of The Clock Come Down The Stairs] we were able to go in with some preparations.”

“A Peel Session was hugely important in several ways,” says Garreth Ryan.

It was seen as a definite personal endorsement by John Peel and in Microdisney’s case, Peel had them in to do six separate sessions.

“This would help airplay prospects, profile and sales next time you came to release a record. And the £30-odd BBC fee for the session was ‘manna from heaven’ to many a hungry artist. the artist could hone their studio craft to a certain extent in the BBC studios. Many of the the Microdisney Peel Sessions serve as a perfect complement to the actual album tracks.”

After so much drama — their tour of Europe had also included a sprint around the Communist live music circuit in Italy — the actual assembling of the record was, Coughlan and O’Hagan recall, relatively free of drama.

“We just got stuck in,” says Coughlan. “With Jamie, we were on solid ground — suddenly all of these songs came into focus for us.”

As with their debut, The Clock Comes Down The Stairs initially went beneath the radar. Within a few years Coughlan and O’Hagan had gone their separate ways, the former leading the heavier, angrier Fatima Mansions, the latter the psychedelic High Llamas. But over time the album’s reputation would grow, with Tom Dunne among those to champion it as one of great Irish albums of the decade.

“I started listening to it late at night at home on my own, probably about 1987,” says Tom Dunne.

I was starting to pick up more on what was at play: Cathal’s lyrics and voice and Sean’s beautiful melodies. It has a very strong emotional core. It’s angry but beautifully expressed. You get a sense of someone raging at injustice and lack of opportunity. That this world wouldn’t give us the chances our youth and talented told us we deserved. And yet it makes you laugh. Over the years I just kept going back to it and picking it as a favourite.

Microdisney perform the Clock Comes Down The Stairs in full at the National Concert Hall tomorrow; and at the Barbican in London on June 9

Life outside of Microdisney

Having taken Microdisney as far as they considered possible, Coughlan and O’Hagan separated amicably. Coughlan channelled his anger into the louder, more punk-influenced Fatima Mansions.

The band created a sensation with their six-minutes-plus 1990 single ‘Blues for Ceaucescu’, though Coughlan was also growing as a balladeer as proved by songs such as ‘Bertie’s Brochures’ (1991). Yet he remained angry, as demonstrated on a cover of REM’s ‘Shiny Happy People’ that didn’t so much skewer the original as douse it in lighter fuel and apply a match.

Having supported U2 with Microdisney, Coughlan was invited to once again go on the road with Bono and chums for their Zoo TV dates, creating controversy when he did something rude to a plastic Virgin Mary on stage in Milan. After Fatima Mansions, he released several well-received solo records.

O’Hagan’s High Llamas became something of a cause celebre in the music press through the mid-1990s, with Steely Dan-esque single ‘Checking In, Checking Out’ receiving heavy airplay.

The High Llamas were a vehicle for O’Hagan’s classic pop leanings — he was openly influenced by Beach Boys records such as Pet Sounds and Holland, as well as by Burt Bacharach. After several well received follow-ups, the group drifted apart.

O’Hagan would also collaborate with Stereolab and was in demand as a producer and arranger, with his long list of employers including such acts as Paul Weller, Kaiser Chiefs and Mercury Rev.