If you love chopping wood, these books are for you

MOVE over, ye warbling Beatles: 50 years after the classic Beatles song Norwegian Wood, and its concluding line: “so I lit a fire, isn’t it good, Norwegian Wood,” there’s a new riff on the title, taking international bookshelves by storm, bringing it all back home, with hearth.

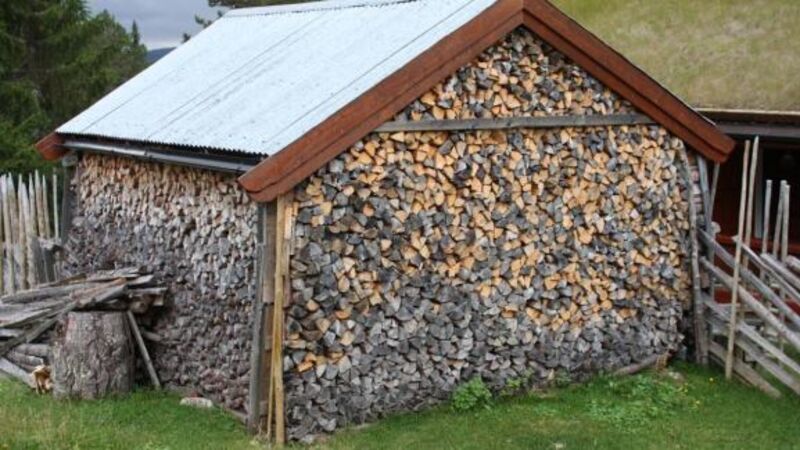

Back home to Norway, firstly, and more crucially, to wood. Back to basics, to wood-burning stoves and wood fires (and pizza ovens at a push,) to forestry, to cords of timber, to choices of chainsaws and axes, to stockpiling timber and drying it for winters to come. Wood as provision, wood as pension and woodpiles — wood as cents and scent, and nature-sent.

Wood, treated right, is money in the bank, heat for the winter ahead: an axis with axes, on which to turn back to something primitive and life-affirming, life sustaining, metaphorical and more.

Funnily enough, today’s chart-storming book title (with the less-than thrilling subtitle) may well have a surprisingly deep resonance with men (and, some very few, women) of a certain post-Ikea shopping age.

It has, I hazard to venture, a particular appeal to gents with more of an affinity to chopping logs than to composing blogs, to those closer in years to the surviving Beatles ( now aged in their 70s,) than to twentysomethings, as John Lennon was, when he penned that Norwegian Wood gem of world music, sitars and all.

That short Beatles’ refrain inspired Japanese writer Haruki Murakimi to pen a coming of age novel of the same title in the 1980s.

Now, ‘Norwegian Wood’ has come around again, this time appended to an English translation of a best-selling Scandinavian book Hel Ved, meaning Solid Wood, by Norwegian journalist and novelist Lars Mytting, who may yet herald a return to simple values of solid hewn wood, and to calories to burn. The axe man cometh.

Whoever really knows when, or why a particular book strikes a chord, and gathers a head of steam so far beyond expectations? Scandi crime novels and TV dramas are a current cultural phenomenon; Sweden’s Ikea (with wood-chip furniture at its heart) has come to dominate the world, but come on — a book about to go global about chopping down trees in the icy northern hemisphere, a book about stacking and drying logs (as we do turf stacks), and burning them for life-sustaining heat, all of it written without a hint of cool irony or a post-modern sneer?

In a digital age, this is something real, tangible, and heart-warming. It also subtly warns about the possible loss of human digits, fingers and toes (if not entire limbs and lives), if an axe is swung carelessly, or when a chainsaw is mistreated.

There might be a certain knowingness about Norwegian Wood’s clever English language title, but as Hel Ved, its original Solid Wood title, it has sold more than 250,000 copies in its native Norway alone, and prompted a TV special of twelve hours length on Norwegian TV watched by 1 million people, with the latter hours of the programme just showing a fire burning down, being rekindled, and sustained.

Don’t be surprised: British and Irish TV show cakes being baked, after all — watched by millions.

Norway’s hold on wood continues in a country latterly swimming in oil reserves. Clearly, it reaches back to more primitive times, when wielding a sharp axe or a splitting tool gave the materials for fire, and for life, and family rearing.

In easily digested chapters spanning themes and topics from The Cold, The Forest, The Tools, The Woodpile, The Seasoning, The Stove and on to The Fire, literary descriptions are interspersed with practical advice on how to sharpen a chainsaw’s links, before spinning them up to 9,000 rpms or a rasping travel rate of 50 mph.

There’s even a note on Newton’s second law of motion for axe swingers, suggesting that a lighter axe moved at speed is more effective than a heavier axe swung with difficulty and grunts. So, handy tip: a three-pound head is plenty for us desk jockeys/ weekend woodland warriors-in-waiting.

Among the references in the book are quotes from Norwegian poet Hans Borli – “The scent of fresh wood is among the last things you will forget when the veil falls” — and American writer Henry David Thoreau whose classic work On Walden Pond has the subtitle ‘Life in the Wood.

There’s even one attributed to Einstein that “people love chopping wood, in this activity one immediately sees results”. As Mytting adds, unlike the endeavours of fishermen, hunters or berry pickers, the fruit of a wood cutter’s labour are always guaranteed, it’s “proper work”. “Each tree is worth its weight in kilowatt hours.

Even the humblest stick can be used, it’s like picking up small change. One day all of those coins will add up to a note. It’s a good feeling.”

It’s not rocket science to know why. It taps quite instantly into a cultural and historical psyche, originating in a country where temperatures dip to the minus 20s, 30s and even minus 40s, where people gather around a heat source, and where — as ever— every adult will remember the faces he or she ever saw in a dancing flame.

Now, like the march of cast iron stoves, Norwegian Wood is making its way steadily southward through Europe, out to traditional post-industrial era coal users like Britain. It’s going to take the huntin’/fishin’/chainsaw totin’ US by storm, and comes to coal and gas importing and bog-reaping Ireland, our home turf.

A country latterly embracing wood-burning stoves and renewable resources with much gusto, and with wood to feed our stoves being imported by masses of cubic metres from Eastern Europe.

Norwegian Wood’s Chapter One, or The Cold, starts off with the simple assertion “gathering fuel was one of the most crucial of all tasks, and the calculation was simplicity itself: a little, and you would freeze. Too little and you would die.”

Scandinavia’s forests allowed the region to be colonised by humans over the centuries, and of necessity, has encouraged sustainable forestry and research, along with development of materials, methods and tools to maximise its potential, and minimise the work needed to harvest it, bring it home and sustain families. Even now, with wood burning back on the rise, one third of Scandinavia is under forest, and each year just 12% of annual woodland growth there is culled for firewood.

This woodcutting bible is an elegantly written textbook with facts, flair, and historical context, it takes us to distant climes, but the trees it talks of — ash, birch, beech, oak, maple, elm, rowan, spruce and the pines – are no foreigners to Irish shores.

Ash is in many cultures, the tree of life, writes Mytting, mixing mythology with material facts: he mentions it is used to make the chassis for Morgan sports cars, but neglects to mention its central role in Irish sport, in the making of the hurley.

Ash’s density is excellent, at 1,200 pound s or 550 kg per cubic metre, and it burns easily due to its low moisture content, which is handy to know for we native Irish, at risk of buying other wet timbers from service station forecourts, which consume as many calories to burn as they return to heat our homes, in our flue-ridden renewable energy, stove-buying sprees.

From start to finish, the beautifully packaged Norwegian Wood is a book that travels far beyond its own climes and culture, while still as rooted as a Norwegian birch. I loved it, and it’s going in fireside pride of place by my wood-burning stove. When I finally get one.

handy adjunct to the Norwegian Woods impulse to go down to the woods today, to chop trees, dry them and burn them in our tomorrows, is quintessential English woodsman Ben Law’s latest book, Woodland Craft.

Law is a well-known eco-builder, woodman and craft worker who’s been based in West Sussex for a quarter of century, in the winsomely titled Prickly Nut Wood.

Prickly Nut Wood may sound like an address from a Monty Python sketch, or an irritation in Embarrasing Bodies, but it’s entirely real, vital and vibrant. Ben Law’s construction of his own hobbity roundwood-framed, woodland home was one of the most popular shows ever on Channel 4’s Grand Designs, and a build highly-rated by Kevin McCloud himself.

Prior to the arrival of coal and coke in Britain in the 17th century, wood was the staple fuel in these islands (we had turf, too), and that meant the prudent management of woodland pastures for on-going supply and that meant pollarded and coppiced woods.

Iin the past decade or two, there’s been a revival in woodland craft and coppicing, dove-tailing with a new-found respect for sustainability in continuous-cover forestry. Ben Law has been the go-to guy to bring issues to the public eye and consciousness, and this new book is where he lays down the ‘how-to’ distilled wisdom he won first hand.

So, whether you are crusty looking to build a bender or a yurt, an artist looking to make charcoal, a farmer looking for a rustic fence, a latter day traveller looking to build an 18’ woodland caravan, a wood-turner learning a bit more about tree species.

Wood types and traits, or to top a shed in shingles and shakes, this is a book to get for Christmas, and to treasure (and be challenged by), for years to come.

Woodland Craft has sketches, photos and projects aplenty over it 218 knowledgeable pages, and is a great place to learn what a bodger is, or what makes a bastard shake. Tip: the latter has nothing to do with a Sussex knee vice, or a dumbhead shaving horse. It’s another world, away in the woods, an environment where nothing goes to waste, not even that which goes up in smoke.